THE GENERALS CIVIL WAR

CIVIL WAR AMERICA

Peter S. Carmichael, Caroline E. Janney, and Aaron Sheehan-Dean, editors

This landmark series interprets broadly the history and culture of the Civil War era through the long nineteenth century and beyond. Drawing on diverse approaches and methods, the series publishes historical works that explore all aspects of the war, biographies of leading commanders, and tactical and campaign studies, along with select editions of primary sources. Together, these books shed new light on an era that remains central to our understanding of American and world history.

THE GENERALS CIVIL WAR

WHAT THEIR MEMOIRS CAN TEACH US TODAY

Stephen Cushman

The University of North Carolina Press | Chapel Hill

2021 Stephen Cushman

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by April Leidig

Set in Garamond by Copperline Book Services, Inc.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

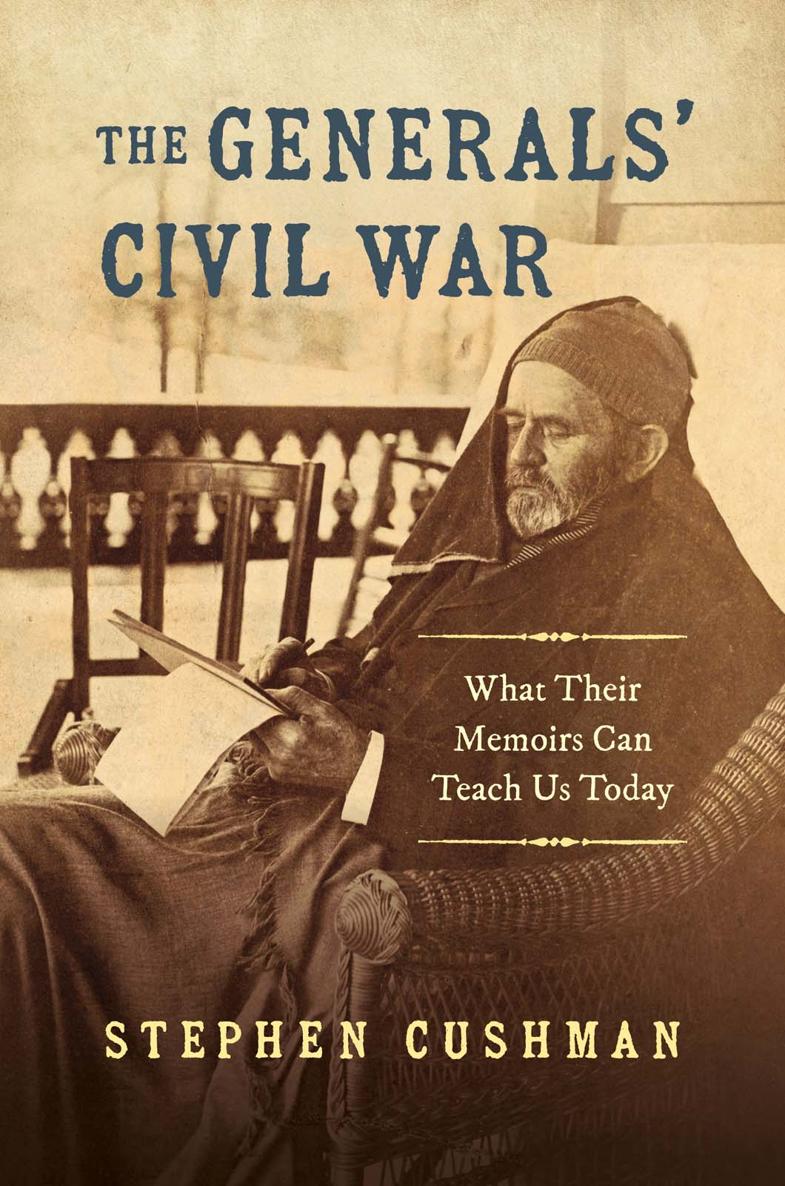

Cover illustration: Gen. U. S. Grant writing his memoirs, Mount McGregor, June 27, 1885. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cushman, Stephen, 1956 author.

Title: The generals Civil War : what their memoirs can teach us today / Stephen Cushman.

Other titles: Civil War America (Series)

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2021. | Series: Civil War America | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021009992 | ISBN 9781469665016 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469666020 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469665023 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Biography as a literary form. | GeneralsUnited StatesBiographyHistory and criticism. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Biography.

Classification: LCC CT21 .C87 2021 | DDC 973.7092/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021009992

One would think that they were works of art.

Ulysses S. Grant to Julia Dent Grant, May 7, 1848, after his trip to the Cacahuamilpa Caverns of Mexico

CONTENTS

Why Generals?

Surrender According to Joseph E. Johnston and William T. Sherman

Destruction and Reconstruction in Richard Taylors Happy Valley

Ulysses S. Grant and the Achievement of Simplicity

George B. McClellans Many Turnings

The Merit of Philip H. Sheridans Memoir Campaign

Coda: Mark Twain and the Mississippi of Memory

THE GENERALS CIVIL WAR

1

WHY GENERALS?

W HY GENERALS? Why read their big books, except for pungent quotations and colorful anecdotes? In the beginning Civil War histories may have fallen under their spell, entranced by their exclusive views of events. But surely with the daybreak of various progressive movements we shook off that spell long ago. The lives of ordinary people in all their particularitythose who for any number of reasons never could have been generals during the American Civil Warhave been commanding more and more attention for fifty, sixty, even a hundred years. And why generals now, when their statues have been vanishing since the June 2015 church shooting in Charleston, the August 2017 rally-turned-riot in Charlottesville, and the May 2020 killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis? In the aftermath of this last event a statue of Ulysses S. Grant, in Golden Gate Park, joined his Confederate counterparts among the toppled or removed. Why should we continue to engage with Civil War generals public writings any more than with their public statues?

To answer that question this book considers a handful of Civil War generals memoirs, printed by New York publishers between 1874 and 1888. Appearing in the last years of Reconstruction and first of Jim Crow, these works fell smack in the middle of the Gilded Age. During these years Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, and Grover Cleveland served as presidents. The first three, all Ohioans, commanded soldiers in battle; the lone Democrat, Cleveland, purchased a substitute to take his place in the army. During these years veterans organizations held reunions, towns and cities unveiled monuments, regimental histories poured forth, and the Government Printing Office began its twenty-one-year publication of nearly 140,000 pages of the official records of the opposing armies. In 1890 the U.S. Congress created the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, and counterparts at Shiloh, Gettysburg, and Vicksburg followed before the end of the century.

These and other developments have attracted closer scrutiny since the mid-1990s, when the term Civil War memory came into common use. That scrutiny has intensified against the backdrop of events fusing molten controversy about Confederate legacies with the divisive 2020 presidential campaign, during which such phrases as another civil war cropped up repeatedly in mainstream publications and on social media platforms. In 1855 Walt Whitman listed the terrible significance of their elections in a catalog of political and social Americana; the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, with less than 40 percent of the popular vote, confirmed the poets assessment. However the American experiment built the Civil War bomb, a presidential election detonated it. Heated national conversations have not ruled out the prospect of another one doing so.

In such conversations another civil war can serve as secular shorthand for apocalyptic anxiety descended from end-of-the-world fantasies originating in the Middle East twenty-five hundred years ago. That this shorthand often has little to do with actualities of the nineteenth-century United States, or their replication in the twenty-first, does not make discussions of Civil War memory any less urgent. Quite the opposite; these discussions have become more urgent. They raise large questions about how Civil War memory has developed, how it has worked, and how it continues to develop and work. This book takes up these questions by looking closely at half a dozen of the best-known memoirs written by Civil War generals. In approaching the memoirs, the chapters that follow braid three strands: the relation of the memoirs to the postwar publishing boom of the late nineteenth century and its new Civil War memory market; the relations between and among memory, imagination, history, and literature; and the relations between audience expectations and first-person narratives by leading actors in historical events. Forerunners of our own recent memoir boom, Civil War generals did to memoir writing what Civil War photographers did to photography; they launched it quickly into public visibility on a newly vast scale. They did so by making public convulsion personal.

Many believe that general officers were the sole suppliers of Civil War recollections until the scales dropped from the eyes of readers who started paying attention to ordinary people. According to this model, Civil War remembering wandered through much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the wilderness of top-down narratives, written by great men on lofty perches, until it passed safely to freedom in the promised land of other peoples bottom-up perspectives awaiting discovery in archives, private collections, attics, and trunks. The problem is, as Ulysses S. Grant put it in a sentence we shall meet again, Like many other stories, it would be very good if it was only true.