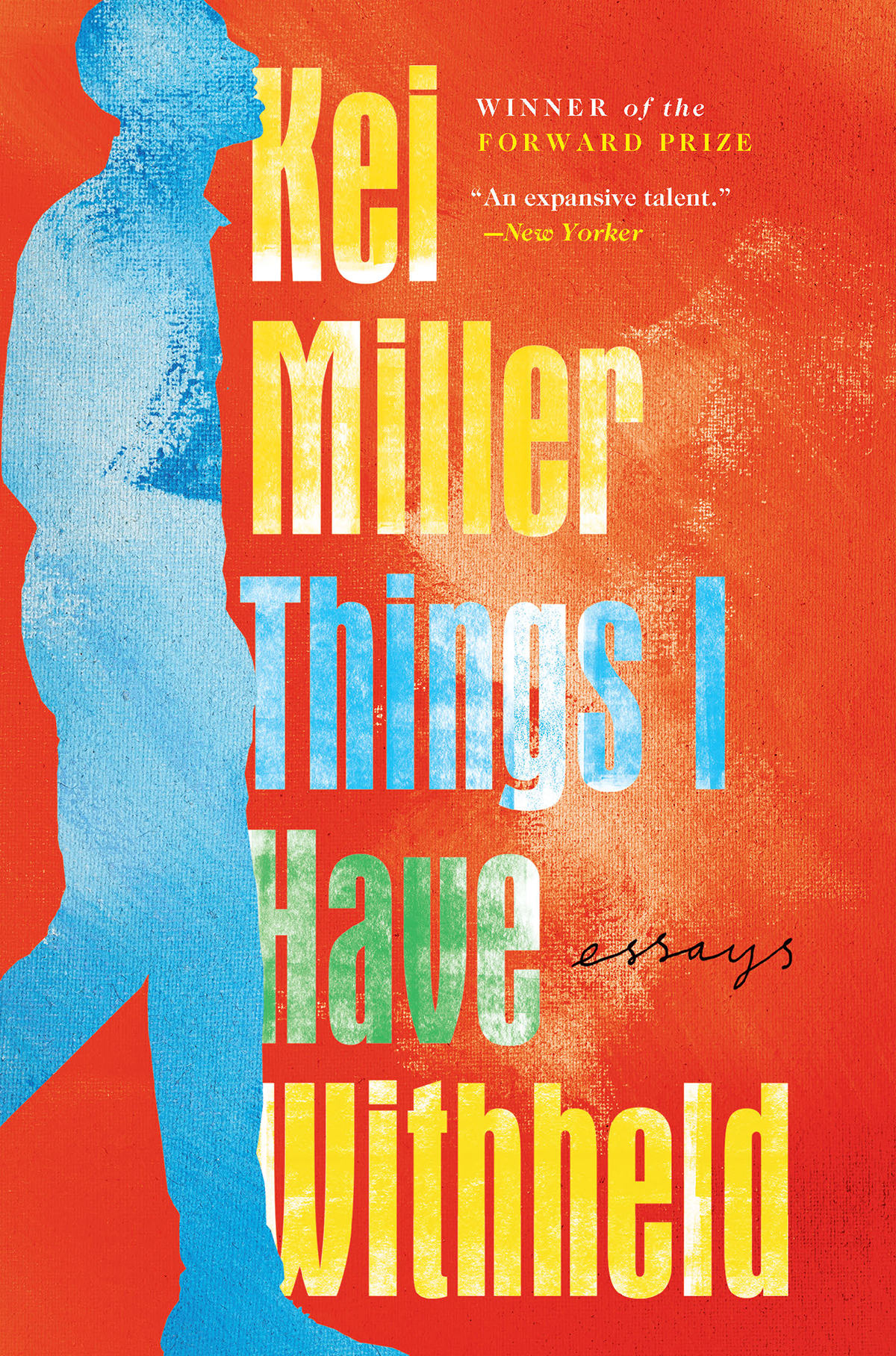

Grove Press

New York

Copyright 2021 by Kei Miller

Jacket design: gray318

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer,who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copy righted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York,NY 10011 or

The following essays have been previously published in slightly altered form: An early version of Letters to James Baldwin was originally commissioned by Manchester Literature Festival and published in the Manchester Review . The Buck, the Bacchanal, and Again, the Body and The White Women and the Language of Bees previously appeared in PREE . Mr Brown, Mrs White, and Ms Black previously appeared in Granta .

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Canongate Books Ltd

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: September 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-5895-6

eISBN 978-0-8021-5896-3

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

For Karen Lloyd and Jaevion Nelson

who not only say, but also do, the most important things.

With all my admiration.

Forty years ago when I was born, the question of having to deal with what is unspoken by the subjugated, what is never said to the master... was a very remote possibility; it was in no ones mind.

James Baldwin, speaking at Cambridge University, 1965

CONTENTS

(An Authors Note)

Letters to James Baldwin

Mr Brown, Mrs White and Ms Black

The Old Black Woman Who Sat in the Corner

The Crimes That Haunt the Body

An Absence of Poets and Poodles

The Boys at the Harbour

The Buck, the Bacchanal, and Again, the Body

Our Worst Behaviour

There Are Truths Hidden in Our Bodies

The White Women and the Language of Bees

Dear Binyavanga, I Am Not Writing About Africa

Sometimes, the Only Way Down a Mountain is by Prayer

My Brother, My Brother

And This Is How We Die

THE SILENCE (AN AUTHORS NOTE)

Consider, for a moment,

the silence

this terrible white

space;

all the things

we never say,

and why?

T his is what comes to mind when I consider the silence: how I saved my words for the stairwell in Streatham Hill, London, right outside the flat where I lived at the time; how I would sit there many nights, a little shell-shocked, and mumbling to myself.

If that sounds a bit like madness, maybe it is because that is what it was. I had ended up in a bad relationship. It was never violent but always volatile. I could never predict what would set things offwhat might produce the latest bout of rage. I felt ashamed as well, to be a man such as I was, such as I amtall and blackand so fearful of a person I was supposed to feel safe with; afraid of doing the wrong thing, and especially afraid of saying the wrong thing. Instead, I saved my words for the stairwellrehashing arguments to myself, trying to unravel them, to understand them, and wondering how I might say things better the next time.

I was often accused of being silent, which was fair. My silence was also a strategya way to survive. Whenever I risked wordshowever carefully, however softly, even if it was just to answer the innocuous question, How are you feeling?it could be met with such an explosive tantrum that I quickly learned to rarely take the risk. The specifics of that experience were new to me; I had never been in a relationship like it before. My reaction, howeverthe way I respondedwas familiar. It was an old habit. Sitting on that stairwell at nights only emphasised what had always been true for methat the moments when I am most in need of words are exactly the moments when I lose faith in them, and when I fall back into silence.

I suspect it is the same for a great many of us. We keep things to ourselves. We withhold them because of fearbecause those things that we need to say, or acknowledge, or confess, or our own failings that we need to own up tothey can feel so important, it is hard to trust them to something so unsafe as words.

The essays that follow are not about the awful relationship, but they are about things I have withheld. The books title is one that I have borrowed from the poet, Dionne Brandsomething she once said at the beginning of one of her own essays, and which I find myself pondering over and over, the way she connects her own body to the bodies of others and the silence between:

Some part of this text we are about to make is already written... for that I am a black woman speaking to a largely white audience is a major construction of the text. Blackness and Whiteness structure and mediate our interchangesverbal, physical, sensual, politicalthey mediate them so that there are some things that I will say to you and some things that I wont. And quite possibly the most important things will be the ones that I withhold.

Each of these essays is an act of faith, an attempt to put my trust in words again. They are attempts to offer, at long last, a clearer vocabulary to the things I only ever mumbled, at night, sitting there on an outside stairwell in Streatham Hill, London.

LETTERS TO JAMES BALDWIN

Dear James,

I wish I could call you Jimmy, the way that woman you described as handsome and so very cleverToni Morrisonalways called you Jimmy, which meant that she loved you, and you her, and that in the never-ending Christmas of your meetings (this is how she described it) you sat, both of you, in the same room, the ceiling tall enough to contain your great minds, drinking wine or bourbon and talking easily about this world. I wish that I could sit with you now and talk that easy talk about difficult thingsthe kind of talk that includes our shoulders, and our hands on each others shoulders, the way we touch each other, unconsciously, as if to remind ourselves of our bodies and that we exist in this world. But here is the rub, this awful factthat you do not exist in this world, not any moreat least, not your body; only your body of work, and I can only write back to that and to the name that attached itself to those words rather than the name that attached itself to your familiar body. Not Jimmy then, but Jamesa single syllable that conjures up kings and Biblesappropriate in its own way, except it does not conjure your shoulders or your hands which I imagine as warm and which I never knew but somehow miss, and I am writing to you now with the hope that you might help me.