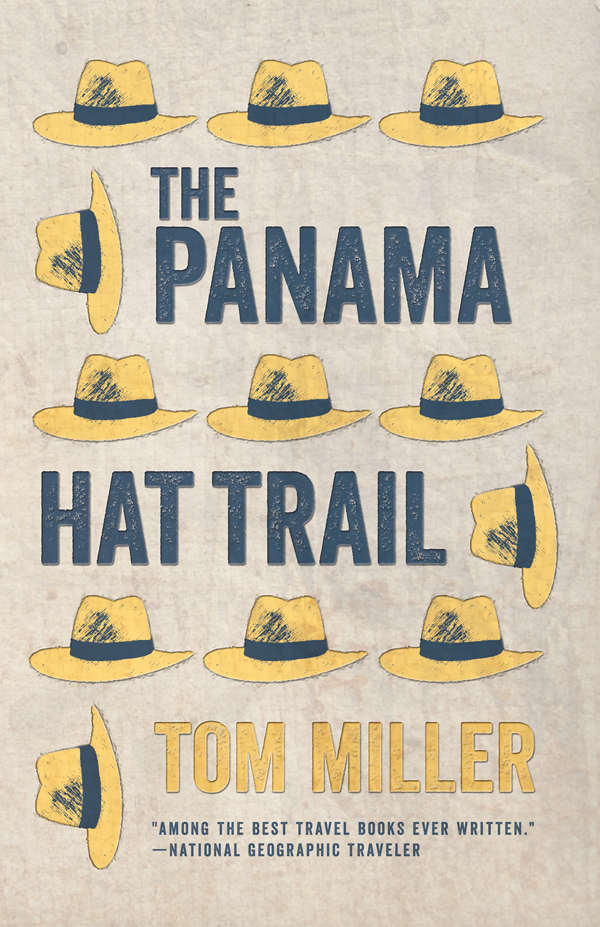

PRAISE FOR THE PANAMA HAT TRAIL

Part reportage, part travelogue, and all pleasure; it is written with enthusiasm and wit.... It is filled with lively anecdotes, pungent asides, vivid scenes, andbest of all in a travel bookdelightful characters.

Washington Post

Absorbing... a lively, entertaining exploration. Chock-full of the enthusiasm and energy of the experienced traveler.... The Panama Hat Trail is an armchair adventure that shouldnt be missed.

Boston Herald

One of the most thoughtful and engaging travel books in recent memory, a superlative job of reporting.... A wonderful book with a rich mixture of native and expatriate eccentrics.

Playboy

Fascinating... like a detective story in which one clue leads to another until the complex fabric of a society slowly reveals itself.

Kirkus Reviews

One eagerly and joyously turns the pages of this lively and vivid account. Each page is loaded with rich treasures.

Latin America in Books

Strange and wonderful characters, rich descriptions, and even richer anecdotes.

San Diego Tribune

Miller has a fine, unobtrusive, offhand way of writing. He is a good and conscientious correspondent who has produced a lively, memorable book.

Outside Magazine

OTHER BOOKS BY TOM MILLER

Trading with the Enemy: A Yankee Travels Through Castros Cuba

Cuba, Hot and Cold

Revenge of the Saguaro: Offbeat Travels Through Americas Southwest

On the Border: Portraits of Americas Southwestern Frontier

The Assassination Please Almanac

EDITOR:

How I Learned English: 55 Accomplished Latinos Recall Lessons in Language and Life

Travelers Tales Cuba: True Stories

Writing on the Edge: A Borderlands Reader

The University of Arizona Press

www.uapress.arizona.edu

1986 by Tom Miller

All rights reserved.

Originally published in hardcover by William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1986

Published in paperback by Vintage Departures, Random House, Inc., 1988

First University of Arizona Press paperback edition, 2017

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3587-3 (paper)

Cover design by Leigh McDonald

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint excerpts from the following: The Donkey Inside, by Ludwig Bemelmans. Reprinted by permission of International Creative Management, Inc. Copyright 1927, 1938, 1940, 1941 by Ludwig Bemelmans. Copyright renewed. Assembly Line, by B. Traven. Reprinted with permission of Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc. Copyright 1966 by B. Traven. El Sombrero de Montecristi, by Lupi. Reprinted by permission of Luis Espinosa Martinez. Copyright 1964 by Luis Espinosa Martinez. Juan CuencaBiografa del Pueblo Sombrero, by G. H. Mata. Reprinted by permission of Centro Interamericano de Artesanas y Artes Populares (CIDAP). Copyright 1978 by G. H. Mata. Folk Arts Thrive in a Quito Shop and City at the Middle of the World originally appeared in the January 16, 1983, and the January 22, 1984, issues of the New York Times, respectively. Copyright 1983 and 1984 by The New York Times Company. Reprinted by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miller, Tom, 1947 author.

Title: The Panama hat trail / Tom Miller.

Description: 2017 edition with new preface by author. | Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017007700 | ISBN 9780816535873 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: EcuadorDescription and travel. | EcuadorSocial life and customs. | Hat tradeEcuador. | Miller, Tom, 1947 TravelEcuador.

Classification: LCC F3716 .M55 2017 | DDC 918.6604dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007700

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3747-1 (electronic)

To Val

PREFACE TO THE 2017 EDITION

If youve peeked at the introduction a page or two from here, youll recall a passage quoting a U.S. State Department officer commenting that Ecuador has a severe inferiority complex. When this book first came out in 1986, I had quite the opposite sensation. Reviews were wonderful, including one in the Washington Post that appeared just days prior to a book signing at Olssons, a since shuttered Georgetown bookstore. Bowls of candy sat by stacks of books. My publisher sent a rep to assure a smooth event. It was a comfortably warm late summer weekday evening, and the casually dressed patrons snaked through the store practically out the door onto Wisconsin Avenue.

A slight hubbub arose as a determined-looking man in a three-piece suit maneuvered his way to the front of the line.

Mr. Miller? He said this more as a statement than a question.

I nodded.

He snapped his card at me. He was Mario Leon-Meneses, counselor from the Embassy of Ecuador.

Mr. Miller, we are very concerned at your characterization of Ecuador as having a severe inferiority complex.

Then, having proven the characterization, Mr. Leon-Meneses turned on his heels and walked out.

The one product Ecuador can feel superior about is the Panama hat, whose name provokes national pride and international confusion. Im not spoiling your reading adventure by stating that Panamas come from Ecuador, but now, even within Ecuador, theres controversy about the various styles of Panamas, their weaves, and their towns of origin.

This is the trail, very roughly, as it has been followed for well over a century: straw cutter weekly straw market weaver middleman factory finishing exporting. In recent generations, however, many weavers have found more lucrative work, and fewer weavers means fewer hats. All this makes for a diminishing industry. In twenty years, lamented the late Carlos Barbern who promoted and sold high-quality hats, the weaving of the Montecristi finos will be all over. That was in the mid-1980s.

Montecristi Panamas are known internationally for their soft, airtight weave and clean, honey-smooth surface. And they originate in Ecuadors coastal region of Montecristi. The finest are more art than headwear. Most Panamas, however, come from the Cuenca region high in the Andes 275 kilometers distant, where midrange hats predominate. That is, except for the very best from the Cuenca region, which are marketed as Montecristi hats. As a result, Montecristi becomes both adjective and proper noun. The confusion: a hat named for the Canton of Montecristi comes from a city called Cuenca, branded as a product of Panama. Well, you can see the quandary of names, quality, and marketing all at once.

Carlos Barberns twenty-year prediction might have come dangerously true, but rather than depress one reader, it inspired him. And so Brent Black, an American close to forty when this book was first published, took a flyer on the Panama hat industry. His goal: encourage the weavers of the Montecristi region and restrict the Cuenca exporters from usingactually misusingthe name Montecristi. His motive: preserve the fine art of hat weaving and reward its weavers. It has only taken him more than thirty years, but Black has made a twenty-first century dent in the nineteenth-century hat trade.

To achieve his goal, Black established a school for weavers in the town of Pile (PEE-lay) in the Canton of Montecristi, where, historically, the best weavers are said to live. Pile children, at age fifteen, can earn an artisan certificate. After five years of training, they might rise to the level of Master Weaversomeone who can produce some 900 weaves per square inch. These are hats which can take up to six months apiece to weave, marketed as

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).