Acknowledgments

For Karen

Writing a guidebook restores your faith in humanity; you meet so many people who are generous with their time, knowledge, and hospitality. The following are just a few of the many people who made this new edition possible.

I am fortunate to have in my family one of the foremost experts on the Panama Canal: my mother, Willie K. Friar. Her expertise and supportnot to mention her networking prowesswere invaluable as always. I dont know how I could ever keep up with the lightning changes in Panama City without help from Mary Coffey, Sandra Snyder, and David Wilson year after year. And trying to do so would be much more difficult and far less pleasant without Clotilde O. de la Guerra and Tony Barrios.

The list of people to thank around the country is now too long for this small space, but I am especially indebted once again to Jane Walker and Barry Robbins in Boquete, Andrea Aster in David, and Carla Rankin in Bocas. Paul Saban and Jim Guy were kind enough to donate terrific photos to the cause. I also am grateful for the many readers who took the time to contact me with tips, updates, and kind remarks.

My colleagues at Avalon Travel once again had to be as patient with me as they are professional. Those who made sure this edition finally saw print include Leah Gordon, Tabitha Lahr, and Mike Morgenfeld.

Most of all, I need to thank my wife, Karen, who not only kept the home fires burning during this endless project but also cut and hauled the firewood. I couldnt have done it without her kind heart, patience, wisdom, and loving support.

The Republic of Panama covers 75,517 square kilometers, which makes it slightly bigger than Ireland and slightly smaller than South Carolina. Panama is young in geological terms. It emerged from the sea just 2.5 million years ago, dividing the Atlantic from the Pacific and forming a natural bridge that connects the North and South American continents. The bridge has allowed North and South American species to intermingle. Known as the Great American Interchange, this mingling had a profound effect on the ecology of South America.

Panamas peculiar shapelike the letter S turned on its sidecauses confusion for many visitors. It takes a while to get used to the notion that the Caribbean Sea is to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. Many also find it strange to be able to watch the sun rising over the Pacific and setting in the Caribbean, or to realize that when a ship transits the Panama Canal from the Pacific to the Caribbean it actually ends up slightly west of where it started.

Panama is at the eastern end of Central America, bordered to the west by Costa Rica and to the east by Colombia. Its far longer than it is wide. The oceans are just 80 kilometers apart at the Panama Canal, near the middle of the country, and that isnt even the narrowest spot on the isthmus. But the country stretches surprisingly far to the east and west; Panama has nearly 3,000 kilometers of coastline along its Caribbean and Pacific flanks.

People often wonder which body of water is the higher of the two. The reality is that theres no difference in elevationsea level is sea level. A locks canal was necessary in Panama not to keep the oceans from spilling into each other, but to carry ships over the landmass of the isthmus. But there is a dramatic difference between the tides on each side. The Caribbean tide averages less than half a meter; Pacific tides can be more than five meters high.

Many visitors are surprised to discover how mountainous Panama is. The most impressive mountain range is the Cordillera Central, which bisects the western half of the country, extending from the Costa Rican border east toward the canal. It contains Panamas highest mountain, Volcn Bar, a dormant volcano that is 3,475 meters high. Another impressive range runs along Panamas eastern Caribbean coast, starting at the Comarca de Guna Yala and ending at the Colombian border. It officially comprises the Serrana de San Blas to the west and the Serrana del Darin to the east, where it enters Darin province.

Most parts of Panama experience few significant earthquakes, which is one of the reasons it was chosen as the site of an interoceanic canal. However, western Panama, particularly Bocas del Toro and Chiriqu, is far more seismically active. In 1991, an earthquake measuring 7.5 on the Richter scale struck along the Costa RicaPanama border, leaving two dozen people dead in Bocas del Toro and thousands homeless.

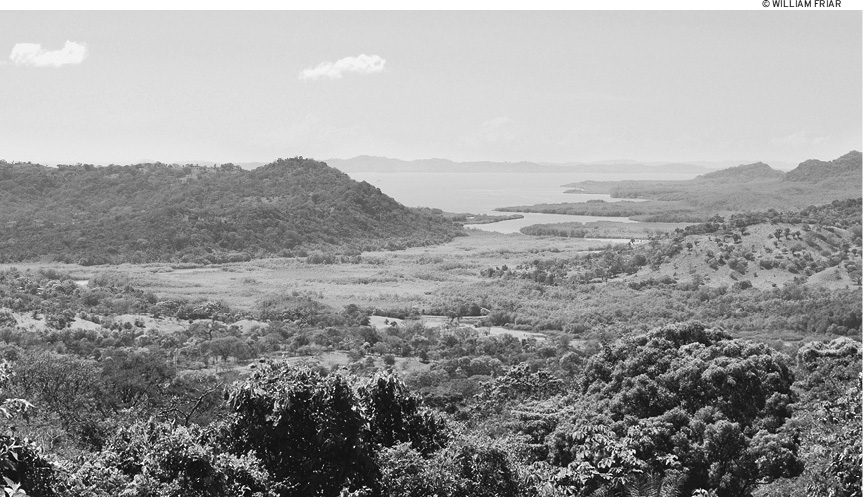

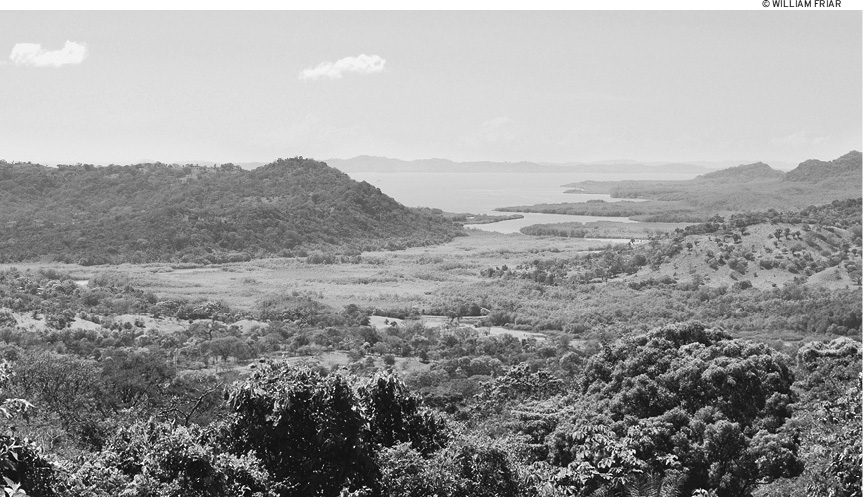

Besides the humid tropical forests that people expect to find, which compose a third of Panamas remaining forests, Panama has a great variety of other ecosystems, ranging from cloud forests to an artificially made desert. Extensive mangroves, coral reefs, and hundreds of islands can be found on both the Pacific and Caribbean sides of the isthmus. Panama also has at least 500 rivers.

AN ABUNDANCE OF THEORIES

The country of Panama gets its name from the city of Panama, but what does Panama mean? No one knows for sure.

The Spanish first used the name in conjunction with a native fishing village they soon claimed as the cornerstone of their new capital. Its little wonder, then, that the most common explanation is that Panama (or, to be proper, Panam) is a forgotten indigenous word for abundance of fishes. Another theory is that the word means abundance of butterflies. Yet another posits that the striking (and abundant) Panama tree lent its name to the city and then the republic. Some say the word just meant abundance, hence the odd variety of plentiful things associated with it. A personal favorite is that it means to rock in a hammock. Take your pick: All definitions still fit.

Panama lies between 7 and 10 degrees north of the equator. The climate is mainly tropical, and days and nights are almost equally long throughout the year. Sunrise and sunset vary by only about half an hour during the year: The sun rises approximately 66:30 A.M. and sets approximately 66:30 P.M.

Temperatures in Panama are fairly constant year-round. In the lowlands, these range from about 32C (90F) in the day down to 21C (70F) in the evening. It never gets cold in the lowlands, and dry-season breezes are very pleasant there in the evenings. It gets considerably cooler in the highlands. At the top of Volcn Bar temperatures can dip below freezing. Humidity tends to be quite high year-round, but especially so in the rainy season, when it approaches 100 percent.

Most of Panama has two seasons, the rainy and the dry. The dry season, also known as summer (verano), lasts from about mid-December to mid-April. Rain stops completely in many parts then, especially on the Pacific side. Flowering trees burst into bloom around the country at the start of this season. Toward the end, vegetation turns brown or dies, and smoke from slash-and-burn agriculture and the burning of sugarcane fields can make the skies hazy.

The rainy season, also known as winter (invierno), generally lasts from about mid-April to mid-December. The rains tend to be heaviest and longest at the end of the season, as though the heavens were wringing out every last drop of moisture. October, November, and the beginning of December are especially heavy. Thunderstorms are a near daily occurrence during the rainy season.

Some parts of Panama, including Bocas del Toro and the western highlands, have microclimates that differ from this general dry season/rainy season pattern.

Yearly rainfall averages around three meters. Its far wetter on the Caribbean side than the Pacific side. The rains in most parts of Panama tend to come in powerful bursts in the afternoon or early evening. Mornings are usually dry on the Pacific side.