Nora left for New York City today.

Thank you for the brooch.

A blustery day and I spent a good part of the afternoon visiting...

Awakened in the night by the wind and this morning I looked out...

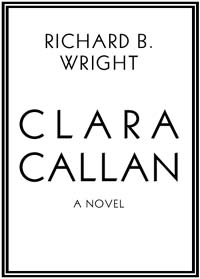

JOHN BEMROSE

HERO

OF THE

HUMDRUM

A PROFILE

OF RICHARD B. WRIGHT

Originally published in Macleans, December 3, 2001.

Wiry and slight, Richard B. Wright sits half-swallowed by a large armchair in his Toronto hotel. For someone whos just swept the Double Crown of Canadian fiction, winning both the $25,000 Giller Prize and the $15,000 Governor Generals Award for fiction for his ninth novel, Clara Callan, the sixty-four-year-old former teacher and book salesman seems remarkably phlegmatic. He admits that all the media attention has given him an interesting glimpse of fame For a little while, all the lenses are trained on you; when the phone rings, its for you.

But he also gives the impression that, once an upcoming Ontario-Manitoba tour is out of the way, hell be glad to get back to the humdrum routines of a writers day. I think Im fairly grounded in the ordinary realities of life, he says. Thats where I come from, and thats where I believe we must find our happiness in the quotidian. Not in these feast days.

Somehow, you can imagine his brisk, no-nonsense heroine, Clara Callan, saying just that. At a time when other Canadian writers have been turning out ambitious novels on such titanic subjects as Hiroshima or the First World War, Wright has stuck faithfully to the kind of modest focus that has sustained his thirty-year career. An unmarried schoolteacher in 1930s Ontario, Clara is the sort of woman who used to be dismissed, if not outright pitied, for a life in which it was widely assumed nothing much happened.

Wright shows otherwise, burrowing into Claras hidden reserves of passion with a skill that makes her one of the most compelling heroines of recent Canadian fiction. Phyllis Bruce, Wrights editor at HarperCollins, recalls her excitement at first reading Wrights manuscript: He caught the female sensibility in a way most male writers never do. I hadnt felt that so strongly since Id read Brian Moores The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne.

Bruce also praises Clara Callans technically brilliant use of letters and diary entries to catch the speech idioms and social atmosphere of the 1930s. Its an era that has a strong hold on Wrights imagination. He was born near the end of it, in 1937, in Midland, Ontario, one of five children in a working-class family. Growing up in the Forties, he felt haunted by the previous decade, not only because his parents talked about it, but because we were still surrounded by the artifacts of the Thirties the stoves and iceboxes and radios and big, heavy cars that were no longer manufactured during the war, when the economy switched to military production. There was still a Thirties ambience.

Wright says he never wanted to be a writer as a boy. A poor student, he preferred history to English classes where, as he puts it, we tortured poems like Brownings My Last Duchess to death. But he began to read on his own, thrilling to such finds as Hemingways short stories, J. D. Salingers The Catcher in the Rye, and Harold Robbins potboilers, which helped ignite a lifelong fascination with New York the city where Claras younger sister, Nora, becomes a radio actor and minor celebrity.

In the mid-50s Wright enrolled in radio and television arts at Torontos Ryerson Institute of Technology, and toyed with the idea of writing for the small screen. It was only after graduation and short stints toiling for a small-town newspaper and radio station that he joined the publishing house Macmillan of Canada in Toronto and began to imagine himself as an author. I had the job of reading through the slush pile, and I loved it, because as bad as these manuscripts were, I just wanted to be close to writers.

In 1968, he was a salesman for Macmillan when he quit to write his first novel, The Weekend Man. Upon its publication in 1970, this modest but very funny tale of a salesman who hates his job made little impression in Canada, but received warm praise when it appeared in the United States the following year. It was the beginning of a career that would draw a loyal if relatively small readership. Wright has always had to work at other jobs to support his family he and his librarian wife, Phyllis, have two grown sons. Ive never expected to make my living as a writer, he says.

Writer Robert Fulford, a member of the Giller Prize jury, thinks that Wrights novels have from the beginning deserved more attention in this country than theyve had. Many readers have been kept away, Fulford suspects, by Wrights focus on ordinary lives. If you were to summarize the subjects of his novels, you would never say they were dramatic or sensational. You might even think there was nothing there. But theres a great deal there. Two months after reading Clara Callan, I still had all its characters in my head.

The four years it took to write Clara Callan coincided with the final stretch of Wrights twenty-year teaching career at Ridley College in St. Catharines, Ontario, where he and Phyllis have continued to live since his retirement last spring. He usually rose at 4:45 each morning to peck away for a couple of hours on his vintage electric typewriter before heading off to the classroom. At first, he had trouble finding the novels voice, but throughout his struggles one idea remained constant: he wanted Clara to have an affair in the Toronto of the 1930s. It was a very different city at that time Protestant, uptight, and Orange, like a little Belfast, he says. I wanted to explore the corruption of the spirit created by that kind of puritanism.

He also wanted to convey Claras pluck in standing up to all that. There is a passage in the book Wright is particularly fond of that catches his heroines state of mind after she leaves an assignation with her lover. Confides Clara to her diary: I am not eighteen years old. I am thirty-four, and have chosen to become involved with a married man. And so there will always be this hurrying from one place to another, with a run in my stocking and that look from the desk clerk as we go out the door.

This moment connects to another of Wrights purposes. He wanted to show how hard life was for people in the Thirties, and not just because of the Depression. A lot of women under forty or even fifty dont realize what life was like in the pre-pill era, he says. Women were often absolutely terrified of an unwanted pregnancy. It could end your career, ruin your life.

Editor Bruce watched Clara Callan make this point when she asked several younger women in her publishing office to read it. A lot of these women are post-feminist, and inclined to be critical of feminist thinking. But Clara Callan opened their eyes. One told me that she suddenly understood from the texture of Claras life how much women were denied by society. By telling what appears to be a period story, Richard has written a book that appeals deeply to younger women.

Surely one reason Clara is so alive to readers is that she was so alive to Wright. I thought of her constantly, he says of the years of composition. Id be talking with someone at school, and my mind would drift to her, to whatever difficulties she was in. Interestingly, he never imagined Clara clearly in a visual sense. I only knew that she was tall, not unattractive, with short dark hair. What really interested me was her emotional appearance. Beneath all that rectitude was a passion for life, and an awareness of the passing of time.