MORE PRAISE FOR ROBERT L. BERNSTEIN

No matter how serious our agenda, Bob Bernstein always leaves me smiling or laughing.... Hidden behind the humor in those anecdotes is a serious attitude: the optimistic courage to volunteer for hard tasks and to find a way on, despite the odds against. I think of this as the Bernstein style. What must be done can be done. Somehow.

Robert Fulghum, author of All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten

When he was at the height of his corporate influence and visibility, Bernstein never flagged in seizing the moment to speak out and act... he showed how success in commerce and the corporate world could be reconciled with the principled exercises of citizenship.

Leon Botstein, president of Bard College

Bob Bernsteins lifetime accomplishments for promoting international human rights, for founding crucial nongovernmental organizations, and for personally helping so many prominent dissidents in their time of need... have been stunning, historic, and transformative.

Harold Koh, former assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights, and labor

Bob Bernsteins leadership in the struggle for human rights is truly peerless in depth and scope.

Trevor Morrison, dean, NYU School of Law

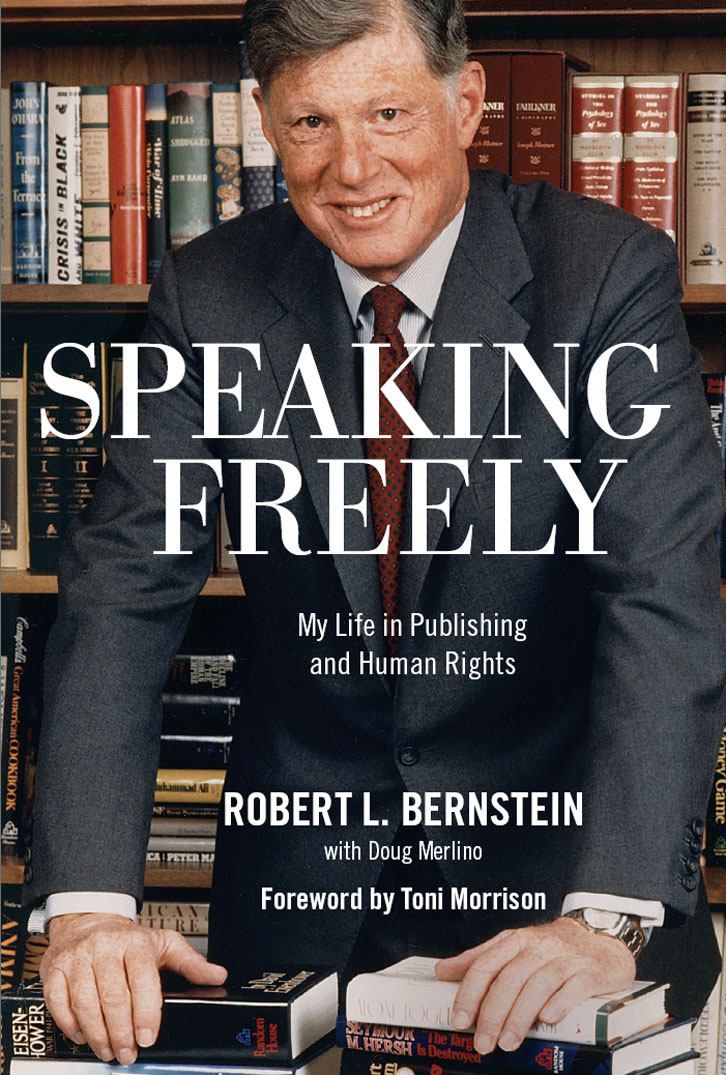

Jacket photograph by Tim Farrell from The Journal News, 1987 Gannett-Community Publishing. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.

Foreword adapted from remarks made in a speech honoring Robert L. Bernstein at the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, 1987

2016 by Robert L. Bernstein with Doug Merlino

Foreword Toni Morrison

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyrighted material in this book. Should anyone be aware of any errors or omissions, kindly provide any corrections to the publisher. These corrections will then be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to:

Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2016

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Bernstein, Robert L., 1923 author. | Merlino, Doug, author.

Title: Speaking freely : my life in publishing and human rights / Robert L. Bernstein with Doug Merlino.

Description: New York : The New Press, 2016. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016001938 (print) | LCCN 2016003084 (ebook) | ISBN 9781620971727 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Bernstein, Robert L., 1923 | Publishers and publishingUnited StatesBiography. | Random House (Firm)History. | Human rights workersUnited StatesBiography. | Human Rights Watch (Organization)History.

Classification: LCC Z473.B43 A3 2016 (print) | LCC Z473.B43 (ebook) | DDC 070.5092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016001938

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all our authors. www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by Bookbright Media

This book was set in Sabon and Berkeley Oldstyle

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my dear Helen, who has broadened my life in more ways than I can count, nurturing our family and creating a world full of joy and purpose

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

by Toni Morrison

I KNEW OF BOB BERNSTEIN IN 1965 (WHEN I JOINED THE L.W. Singer Company, based at that time in Syracuse, New York, but recently purchased by Random House and already scheduled within the year to move to New York City). I met him in 1967 when he visited that subsidiary. I remember a cigar (Fidelistic), height (much too tall), and restless, impatient eyes. The cigar was gone the next time I saw him, but the height remained as did the impatience. But the restlessness seemed to have been replaced with what I understood now to be an intense curiosity: things interested him; people interested him; ideas interested him. I had had only one employer like that beforesomeone who cherished knowledge for its own sake, got passionate about it, and who was willing to act on that knowledge and passion in ways not immediately (or even ultimately) beneficial to himself.

Since that meeting, fifty years ago, there have been many more, and I came to know him both as employer and friend. It ought to be a contradiction in terms: boss and friend. It ought to be a contradiction because one of the deepest pleasures of working at a certain level in a company, or a factory, or a university, or a laboratory, or a shop, is the real joy one can take knowing not only that your boss is not your friend, but that you can do his work better, and that you are secretly or obviously better equipped to run the place than those who do. That if only they would do what you advised, all would be well.

Robert Bernstein deprived me of that joy by becoming a friend I could rely on, instituting or examining and dismissing all the improvements I could think of. And Random House prospered, thrived, flourished in spite of the fact that he refused to take directions from me. A great deal of that prosperity I connect with that impatience and curiosity that I noticed in 1967. Impatient with obstacles to first-rate work, he was curious about what might be a better way and what other people thought. What is wrong, he seemed always to be saying, and how can I fix it? Or, as he said to me once, when I was trying to make an important decision about my work life: If you had it like you wanted it, what would it be? No one had ever asked me that before (or since) and it humiliated me to think I had never asked it of myself. It also overpowered me to hear it from my employer (who need not have concerned himself) and from a friend (who clearly was concerned). What it said to me was: Difficult things are possible, problems can be solved if you are clear in your own mind about your purpose. It may sound obvious now, but then, at that moment, it was the opening of a small gate in my personal China Wall. It was a moment that crystallized the clarity of purpose that had been evolving in him during those years since 1967.

Robert Bernstein presided over a company in the business of turning ideas artfully expressed into profit. Somewhere along the line, he got interested in turning profit into ideasin being insistent on the rights of authors to say what they wished and to let the worth of the saying rest on its own merit, which might not coincide with the desires of the marketplace. The resources of the company at his insistence were well used in defending the rights of Marchetti and Marks (The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence) against the restrictions of the CIA; the resources of the company were well and significantly employed in the publishing of public servants and dissident writers who could be and were perceived as commercially unpromising. His disdain for the hot but corrupt title on the horizon was legend among us. And always this tremendous curiosity: What if... followed by the determination to do something about it. Is a new employee badly placed? Where should he or she be? Are there other Black people who might want to work in publishing if they knew about it? Recruit them, gather them, and give them real jobs rather than hopeless summer vacations in the stockroom. Is the entering salary too low? What is competitive and lets change it. Is there an imprisoned, shackled, tortured, defenseless writer? Where? And how can he or she be helped?