Foreword by Richard Holbrooke

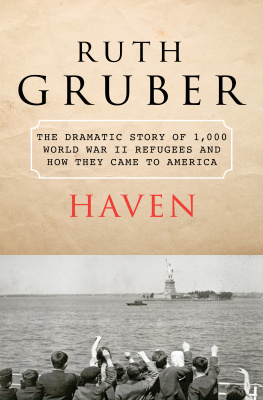

You could not invent Ruth Gruber, not even in a movie (although Natasha Richardson did play her in Haven, a movie based on her efforts to save refugees in the middle of World War II). But Ruth Gruber is very real; she is ninety-five, and she lives in a splendid apartment on New York's Central Park West.

Visitors to apartments on Central Park West usually look first at the magnifi-cent views of the great park. But a visitor to Ruth's apartment will hardly look outside. It is what is inside the apartment that commands attention. The walls are coveredand I mean coveredwith art and artifacts from her life: folk art and mementos from Alaska and Ethiopia and Israel; works of art by Chagall and Mir; photographs of Ruth with Eleanor and Hillary and Golda, with FDR and Ben-Gurion and Hammarskjld and Truman and Ickes; letters from grateful people who owe their lives to Ruth; testimonials and awards from the great and near-great; pictures of her children and grandchildren. And at the center of all this history is an astonishing sight: a tiny, ninety-five-year-old dynamo who rushes around answering the telephone, opening the door, quickly finding exact passages from books in her vast library to illustrate specific points. She remembers everything, swiftly correcting me, for example, on how we first met (through my wife, Kati Marton, she reminds me, who interviewed her for a book on George Polk, the CBS correspondent murdered in Greece in 1948).

If our nation had officially designated living national treasures (as Japan does), Ruth Gruber would certainly be among them. Her career has spanned eight decades, and while she proudly broke the gender barrier time and time again, she never sought recognition simply for being a woman; as her niece, Dava Sobel, wrote in the introduction to the 2000 reissue of Haven, Ruth pioneered without even realizing that she was spearheading a movement. (Sobel was referring to the fact that Ruth had her first child when she was forty-one, at a time when late motherhood was considered dangerous and in slightly bad form.) Ruth could have been a big star, in the modern sense of the celebrity-journalist, but she never sought personal publicity, although as an attractive and very young woman who many thought resembled Myrna Loy, she got a lot of attention which she knew how to use to gain often unprecedented access to people and stories.

But Ruth's primary interest was the fate of the people she covered. She was invariably drawn to the downtrodden, the forgotten, the drive-by victims of history. When she heard in January 1944 that President Roosevelt would finally permit one thousand refugees into the United States, she was a special assistant to the legendary Harold Ickes, FDR's secretary of the Interior, working first as his field representative for Alaska and then as his special assistant. Within hours she was in Ickes's office, asking to be sent to Italy to escort the refugees on a secret convoy across the Atlantic. Thus the experiences that became the book, and later the movie, Haven.

Her fearlessness had been established long before that. She had gone to Germany to study in the early 1930s, seen the rise of Hitler, and returned to New York at the age of twenty a minor sensation, billed by The New York Times and other newspapers as the world's youngest Ph.D. She wrote her doctoral thesis for Cologne University on Virginia Woolf; it was probably the first scholarly study done on the great British writer. (For this achievement she was summoned to a meeting with the mayor of Cologne, a man named Konrad Adenauer, and three years later she met the great writer herself, who described the meeting in her own diaries and letters in vaguely antiSemitic and highly snobbish terms.) Her thesis was finally published in the United States in 2005. Unable to find a full-time job despite her achievements, she talked her way into special assignments for the New York Herald Tribune.

In 1935 and 1936 she managed to visit the closed Soviet Far East, penetrating the local branch of Stalin's secret police in Yakutsk, in the heart of the gulag, to the amazement of her jealous male colleagues. Her articles changed her more than they changed the gulag or her readers; they unleashed her lifelong concern for the oppressed, the voiceless, the homeless.

But Ruth Gruber was Jewish, and after her early experiences in Germany even though she had originally loved Germany, its language, and its culture the mid-century crisis of the Jews gradually became her primary concern. Starting with her covert mission for Ickes and FDR nine years later, Ruth would become the chronicler of every major Jewish emigration to Israelfrom North Africa, Yemen, Iraq, Romania, Russia and Ukraine and the rest of the Soviet Union, and finally from Ethiopia, where, in her mid-seventies, she scrambled up and down muddy fields to find Jews living in dangerous and terrible conditions in the highlands. As well, she would witness the struggle of the Jews to create their own homeland, and she would become a passionate supporter of Israel.

If Ruth had done nothing else in her remarkable life, she would still be remembered, of course, for her book on a desperate group of Jews who kept trying to get into pre-Israel Palestine on an aging ship they had renamed the Exodus1947. From her journalistic, factual account (which she originally called Destination Palestine), Leon Uris got an unforgettable title and the general plotline for his famous novel and the film that followed. Uris's one-word book title took on a new meaning in English, a shorthand for the painful, seemingly endless quest of Jews for a homeland.

In the book you hold in your hands, Ruth has chosen the best photographs of her long career. The selection, her editor, Victoria Wilson, has told me, was extremely difficult and often painful. The pictures of the Soviet Arctic and the gulag and Alaska record a world gone forever. And the photographs of the terrible ordeals suffered by Jews trying to make their way to Israel, from the Exodus to Ethiopia, bear essential witness to the painful birth throes of the Jewish state. But in the end, Ruth and her editor made a brilliant selection. Scenes that once seemed ordinary have taken on, with the passage of the years, an iconic character, summing up lost worlds. Look at them again: they are anything but ordinary. Study the faceswhether of Eastern Europeans who survived Hitler's death camps, or of young, confident Israelis ready to fight for their country, or of Ethiopian Jews yearning for their children who have made the dangerous voyage to Israel. Ordinary people, fighting for dignity and survival. Ruth Gruber's lens also captures the greats, especially the leaders of Israel, as they begin their fight for survival. Side by side, the ordinary and the great: the effect is powerful.