Breathes there a man, with soul so dead,

Who never to himself hath said,

This is my own, my native land!

Walter Scott,

TheLayoftheLastMinstrel, 1805

We have got the second volume of EspriellasLetters, and I read it aloud by candlelight. The man describes well, but is horribly anti-English. He deserves to be the foreigner he assumes, wrote Jane Austen in October 1808 of the book in which Robert Southey, posing as a Spaniard, offered a critical commentary on England. She was intensely, and to me endearingly , xenophobic. The idea of a fashionable bathing place in Mecklenburg! How can people pretend to be fashionable or to bathe out of England! she exclaimed in 1813 in reply to a letter from her brother Frank, then serving in the Baltic Sea. More seriously, perhaps, she wrote of an acquaintance the year after Waterloo, He is come back from France, thinking of the French as one could wish, disappointed in everything.

Revolutionary France had not even the initial appeal for Jane Austen that it had for her contemporary, Wordsworth. In her view the stability of the English political, social and religious institutions offered the individual the safest degree of freedom within an ordered framework by which to live a satisfying and worthwhile life, without impinging on the rights of others.

Her affirmation of the superior sense and moderate behaviour of the English nation finds amused expression in NorthangerAbbey when Catherine Morland compares the Alps and Pyrenees with the Midland counties of England and decides that in the latter, the laws of the land and the manners of the age provide security against anything too terrible happening. Furthermore, among the English, she believed, in their hearts and habits, there was a general though unequal mixture of good and bad.

Jane Austen pokes gentle fun at the nave Catherine, but in Emma, a more mature heroine surely expresses her creators thoughts as she surveys Donwell Abbey, with its surrounding woods, meadows, river and farms. It was a sweet view sweet to the eye and to the mind. English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a sun bright, without being oppressive. Natural endowments and what man has, by taste and ingenuity, made of them, are bound up together and celebrated in a profound love of England, its prosperity and beauty.

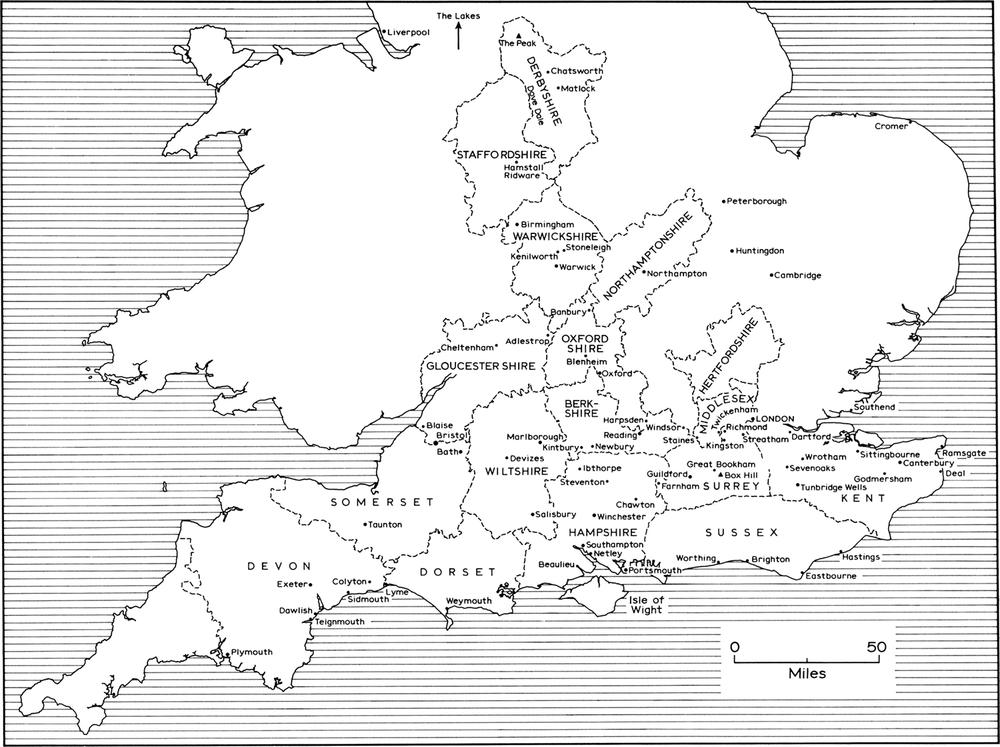

How much of England did Jane Austen know? Like Catherine Morland she was confessedly ignorant of the northern and western extremities. But it is not true as some think that she rarely ventured beyond Hampshire and Bath. Her travels took her through fourteen counties, some of them repeatedly; she knew three cities intimately, and she was acquainted with many stretches of the English coastline. It can be said that the whole of southern England was her territory. Farms, villages, country estates, market and coaching towns and seaside resorts were known to her in great number. And this was at a time when every place had more local flavour in terms of agricultural produce, building materials and the character and function of each town than today. We cannot doubt that when travelling she took the same pleasure and interest as her own Fanny Price in observing all that was new, and admiring all that was pretty in observing the appearance of the country, the bearings of the roads, the difference of soil, the state of the harvest, the cottages, the cattle, the children.

As Jane Austen knew and as her sister Cassandra once wrote, in this life there must be always something to wish for, and even England was not perfection on earth. In the same novel that expresses delight in the Donwell scene, Emma, having paid a charity visit to a poor cottager, stops to look once more at all the outward wretchedness of the place, and recall the still greater within. That was in a village; in the cities conditions for the poor were yet worse, and neither the noise and disorder of Portsmouth , the bad smells of Bath nor the polluted atmosphere of London escape Jane Austens censure. Yet visually, at least, even the cities presented little ugliness, in comparison with what they would become. In the novels of Jane Austen, towns offend almost every sense except the sight.

It is with Jane Austens reaction to the visual world about her that this book is chiefly concerned. It is not a guidebook that has been admirably accomplished already nor is it founded on speculation, on the amusing but in my view misguided game of identifying this village or that house as the original of some place in the novels. I firmly believe that Jane Austen was quite capable of inventing entire a Mansfield or a Barton, a Rosings or a Highbury, and that to try to match them up with real locations is as fruitless as it is insulting to her imagination.

Instead I have attempted to explore what her experiences of the English countryside, in all its component parts and all its regional variety, meant to her. She was indeed fortunate to live in an age when not only was England at the peak of its physical beauty, improved but not yet desecrated by human activity, but when cultured people were learning to appreciate the natural world after centuries of indifference or fear. During the course of her life, her ideas on landscape underwent subtle changes as she absorbed and responded to contemporary thinking, and as her reading was supplemented by personal knowledge. These ideas, and their influence on her novels, are the particular pattern in the carpet that I have chosen here to trace.

My own understanding of the background to Jane Austens work has been greatly enriched in the process of researching this book, as I have delved into the eighteenth-century attitude to the environment a subject that, as Margaret Drabble too rightly says, engrosses those who become involved in it

Notes

. LettersfromEngland;byDomManuelAlvarezEspriella, 1807.

.AustenPapers.

. Anne-Marie Edwards, InTheFootstepsofJaneAusten is a good present-day guide to many of the places referred to in this book.

. Margaret Drabble, AWritersBritain.

look around

Upon the variegated scene of hills,

And woods, and fruitful vales, and villages

Half-hid in tufted orchards, and the sea

Boundless, and studded thick with many a sail.

William Crowe, Lewesdon