THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2016 by

Robert Hale, an imprint of

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

www.halebooks.com

This e-book first published in 2016

Maggie Lane 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 71982 059 5

The right of Maggie Lane to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

In a lifetime of thinking, talking, reading and writing about Jane Austen, I have found ever more to ponder and to admire in her novels. The essays in this book first appeared in the Regency World magazine as subjects occurred to me over the years.

In making my selection for this more permanent form, I have chosen those which celebrate the quirkiest corners and cleverest contrivances of Jane Austens art. The title comes from the first essay, but it is also an invitation to spend time with a well-loved author in the comfort and intimacy of close quarters.

My special thanks are due to Professor Lorna Clark of the Burney Society, whose quest for an image so serendipitously sent me looking back through old issues of Regency World, and to Editor Tim Bullamore for giving my new project his blessing. On the Sofa with Jane Austen is dedicated to all my dear friends and colleagues in the Jane Austen Societies of the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada and Australia. I am particularly grateful for the support and interest of fellow writers Angela Barlow, Penelope Byrde, Susannah Fullerton and Hazel Jones, and for technical assistance to Hazels husband David Brandreth.

Maggie Lane

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

NOTES

The Mirror of Graces, 1811; reprinted R.L. Shep, 1997.

Byrde, Penelope, Jane Austen Fashion, Excellent Press, 1999.

Austen-Leigh, James Edward, A Memoir of Jane Austen, 1870; reprinted OUP, 2002.

In conversation with the author, February 2016.

Austen, Henry, Biographical Notice of the Author, with Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, John Murray, 1818; reprinted with James Edward Austen-Leigh, A Memoir of Jane Austen, OUP, 2008

Bryson, Bill, A Short History of Private Life, Doubleday, 2011.

The series was accompanied by the book: Vickery, Amanda, Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England, Yale, 2009.

Austen, Caroline, My Aunt Jane Austen, The Jane Austen Society, 1991; also reprinted with Austen-Leigh, 2002.

Lane, Maggie, Jane Austen and Food, Hambledon, 1999; also ebook Endeavour Press, 2014.

Jane Austens Letters, Collected and Edited by R.W. Chapman, Second Edition, OUP, 1979; Jane Austens Letters, Collected and Edited by Deirdre Le Faye, Fourth Edition, OUP, 2011.

Austen, Caroline, 1991.

Cassandra Austens Note of the Date of Composition of her Sisters Novels, private possession, reproduced in R.A. Chapman, The Works of Jane Austen, Volume VI, Minor Works, OUP, 1965.

Advertised on a playbill for the Theatre Royal, Bath in February 1795 as a musical entertainment. Tom Bertram refers to it as an afterpiece, which it originally was, but it proved so popular that it often became the main item on the bill. The farce was written by Prince Hoare in 1793.

ON THE SOFA

T hat fashionable article of eighteenth-century furniture, the sofa, appears in several of Jane Austens most telling scenes. The word sofa came into the English language with travellers returning from the East, where it denoted a raised platform strewn with rich carpets and cushions for sitting and lounging. In Europe, as increased leisure required greater comfort in the home, the name sometimes spelt sopha was adopted for the elegant item of upholstered furniture that became an essential feature of genteel English drawing rooms. William Cowper, a favourite poet of both Jane Austen and Sense and Sensibilitys Marianne Dashwood, celebrated what he saw as a remarkable age of comfort with his long poem The Sofa, which forms part of his major work The Task.

In the poem the speaker marvels at the ingenuity of man for inventing such aids to luxury and ease as the sofa:

Thus first necessity invented stools

Convenience next suggested elbow chairs

And luxury the accomplished sofa last.

The speaker then takes a long and contemplative walk through the English countryside before returning for a well-earned rest on the sofa:

Nor sleep enjoyed by curate at his desk

Nor yet the dozings of the clerk are sweet

Compared with the repose the sofa yields.

The intriguing possibilities that distinguish the sofa from an ordinary chair for fictional purposes are, of course, the fact that it can be shared by two or more people; or, conversely, that it can be hogged by one person and used to put their feet up. Jane Austen exploits the possibilities of the sofa to illustrate idleness, illness (real or imaginary) and intimacy. Though most of her references to the sofa come in the novels of her later period, as early as her childhood writings she shows the sofa put to absurd use. For example, in Love and Freindship the two heroines Laura and Sophia are described as fainting alternately on the sofa, while a two-year-old prodigy has the sofa to herself in Lesley Castle. In Pride and Prejudice, dull-witted Mr Hurst, denied the game of cards he desires after dinner, has nothing to do but to stretch himself on one of the sofas and go to sleep.

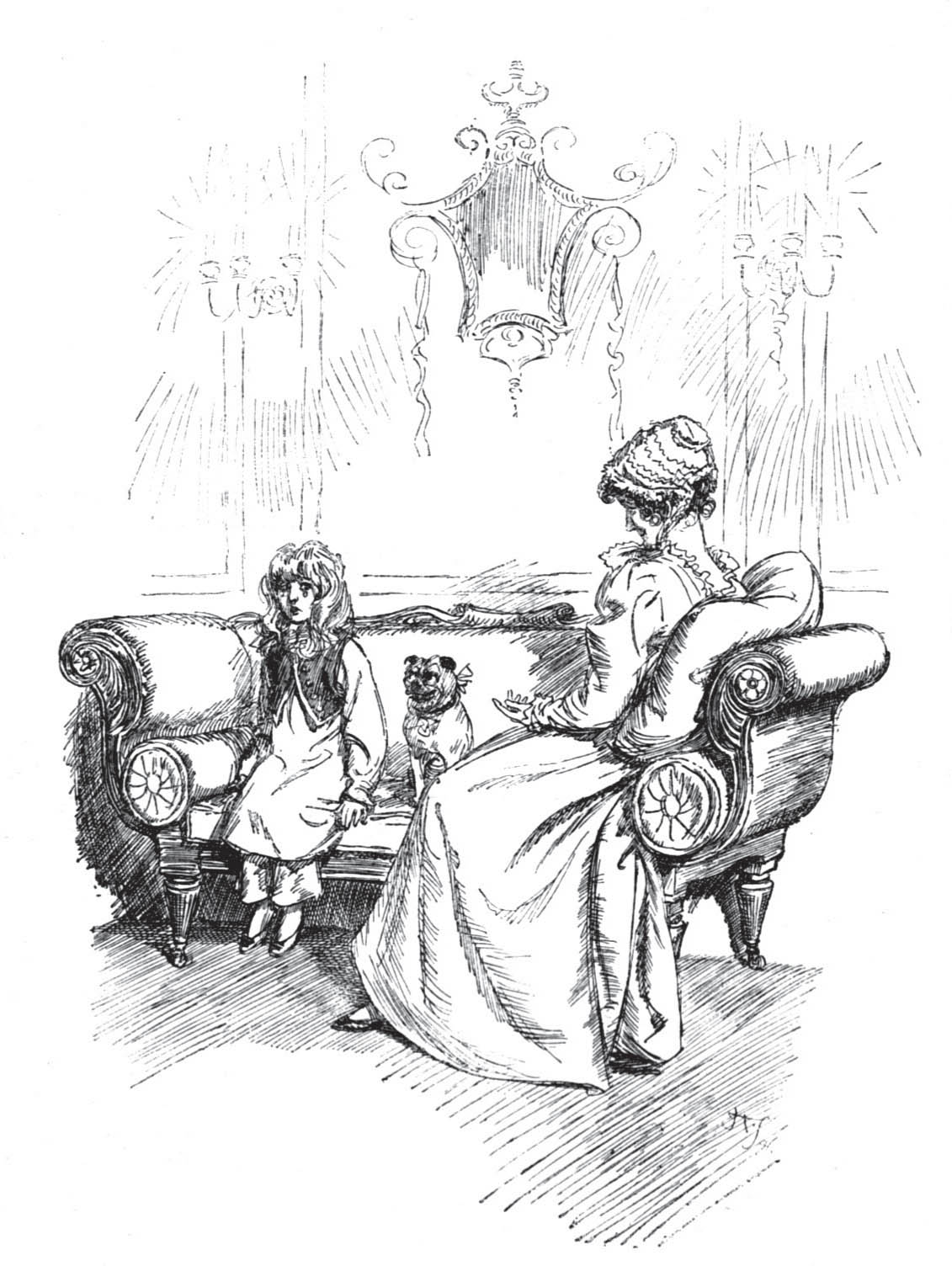

The personification of idleness is Lady Bertram, firmly anchored to her sofa throughout Mansfield Park:

She was a woman who spent her days in sitting, nicely dressed, on a sofa, doing some long piece of needlework of little use and no beauty.

That she occupies a sofa rather than an ordinary chair suggests that she often has her feet up, leaning back at one end:

Lady Bertram, sunk back in one corner of the sofa, the picture of health, wealth, ease, and tranquillity, was just falling into a gentle doze.

Only on two occasions does she apparently lower her feet to make room for somebody else. Once is when the child Fanny first arrives at Mansfield Park, and Lady Bertram invites her to sit on the sofa with herself and her pug; the only other instance is when Sir Thomas returns from Antigua and she becomes so unusually animated:

as to put away her work, move pug from her side and give all her attention and the rest of her sofa to her husband.

Later, while the preparations for the ball go on all around her, Lady Bertram continued to sit on her sofa without any inconvenience, and she is still on the sofa during the ball itself, as:

Next page