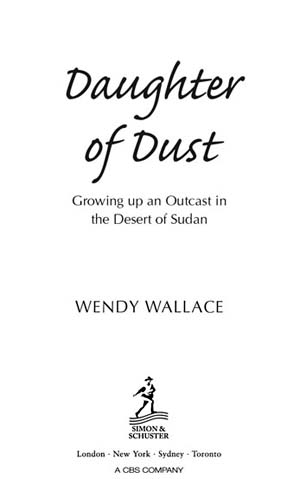

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2009

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2009 by Wendy Wallace

This book is copyright under the Berne convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Wendy Wallace to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

This is a work of non-fiction. While all major events of Leilas life are true, names and details have been changed. Some minor characters are composites and some childhood events are reconstructions.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia

Sydney

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781847375308

eBook ISBN: 9781847378422

Typeset in Palatino by M Rules

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays, Chatham ME5 8TD

For the abandoned everywhere

Contents

Prologue

The room is always different, always the same. The light is dim, the concrete floor covered in fine, red dust. The cots are still there, their bars dented, the paint worn away. The air is thick with the smell of urine, sickness and grief. The sound of crying bounces from the walls, echoes inside me.

I move from one cot to the other, picking up the children one by one. I hug them, kiss them, laugh with them. As I hold them, they grow calm. As soon as I put down one child, another begins to scream. I move from child to child, trying to give them what they need.

The smallest lie two to a cot, bottles propped in their mouths. In one cot is a bundle, wrapped in white cloth. It is stiff. Silent. Two more arrive under a nannys arm, wriggling in a torn towel. She lays them on a mattress, naked and screaming.

I step outside, into the brilliant, relentless light. The veranda where we used to play lies empty; a plastic swing hangs motionless. A breeze rises and the seeds of the Beard of the Pasha tree shiver and rattle in the silence.

I know only one thing. It is my responsibility to help these children.

Chapter 1

ABANDONED

I wake to the thump of my own heart, my cheek stuck to the rubber mattress. Flies crawl around my eyes and into the corners of my open mouth. I smell the milky sourness that comes from a roomful of children, sense the warm air on my limbs. For a minute, I lie without moving, absorbed in these sensations that tell me I exist. I am alive.

Then, Im all yearning.

I wait for a voice that doesnt come. A familiar smell, of bitter oil mixed with perfume. Arms that encircle me. A face I know. But theres nothing. Im hungry. I begin to yell. I hear my own crying and scream more loudly; the roar fills my head, pierces my ears, until there is nothing in the world but my screaming.

My fingers find the cool bars; as I grip them, my crying slows. Crying is useless. Crying brings nothing. I pull myself up, still searching for the face that doesnt come. I bang my head against the metal. Feel the judder that runs through the bars and back into my hands. The jarring of my head against the cot tells me there is something there. Bang, bang, bang.

I can hear other kids doing the same. Banging. Rocking. Thumping.

Its during these days, these months, before I can speak or think, that the unfuture closes around me. The unfuture is a state of emptiness, of waiting, that never ends. Of wanting, that dwindles to hopelessness.

Milk keeps me alive. I clench the bottle between my hands, sucking hard on the teat. I swallow every drop and when its finished I scream for more. I chuck the empty bottle over the bars; it clatters on the floor. I pause, and look at the way it rolls, empty. Then I begin to yell again, this time banging my head on the wall.

This is my life, given to me by Gods will. I wont let it go.

*

A year later, or maybe two, I emerge from Mygoma orphanage, alive. Three of us leave together in a car: me, Amal and Wagir. I am on the seat next to the window, Amal is in the middle and Wagir bounces on the lap of a nanny. No one comes out to see us off. The taxi bumps and lurches over the potholes as it pulls away into the ordinary day. We sit in the back, startled by the light, the noises, the smells.

Amal and I wear the same new cotton dresses, in a pattern of squares with a bobbly texture. The shoulders hang down on our elbows; the hems droop to our ankles. For the first time, I have shoes on my feet. White plastic sandals, strapped tight. I am using one shoe to try and prise off the other when the nanny reaches over and slaps my calf. She wipes away the snot coming out of Amals nose.

God protect us, she mutters, pulling her tobe further forwards over her face. What is to become of such children?

I look at her. I dont understand words. Only voices.

The air smells of dust and exhaust fumes, of bean patties frying at stands by the side of the road and the mornings bread, carried in baskets on womens heads. Schoolchildren wait in crowds for buses; goats stand on their hind legs, biting at the leaves on the branches of trees. Lines of cars queue at petrol stations; men exit from the mosque, pulling on their shoes.

The taxi driver winds down his window and calls out to people for directions. He stops in front of a high wall with wrought-iron gates set into it. He leans on his horn and a man emerges and drags open the gates. He sees me staring at him and brings his hand up to his forehead in a sharp salute. The car rolls up a sandy drive edged with bushes, to where a woman stands waiting on the steps of a big house with shuttered windows.

I dont want to leave this car. I get down on the floor, behind the driver, grabbing hold of the bottom of the seat. The nanny drags me out by my arm. A crowd of children gathers, all taller and older than me. They surround us, staring at us. In front of me is a girl with a round, dark face. She has two plaits, small teeth, quick eyes. She steps forwards, grabs me under my armpits and lifts me up. She holds me against her chest, staggers, then slides me on to her hip. I recognize the pressure of her arms, the strength of her body. She is part of a dream I once had. The circle of children, the smell of blossom, fall away as I grope after something out of reach, below the surface of memory.

The girl hugs me hard and, without warning, drops me on to the sandy ground. She walks off. The children laugh and suck their fingers. The nanny climbs back into the battered yellow taxi and it slides down the path to disappear through the open gates.

*

What are you waiting for? A woman stands over my bed. She twitches the sheet off me with one hand and with the other lifts me by my arm on to the floor. I feel the chill of the tiles under my feet, see the dizzying pattern of leaves stretched over her belly at the height of my head.

Whats your name?

I stare at her face.

Copy the others, she says, leading me towards the door. And youll be all right.

So begin my days at the Institute for the Protected. This bed is the centre of my new world. I wake up in it, dizzy from the lack of bars. I wriggle against the wall, press my spine against the plaster, for something solid to tell me where I end and the world begins. The room is full of birdsong; light forces its way around the shuttered window, and falls in stripes and diamonds across the walls. The sheet underneath me is made of rough blue cotton. Below the bed is a brown tiled floor, measured out in squares. A curled shape rests under another sheet on the far side of the room. I know without thinking about it that it is Amal.

Next page