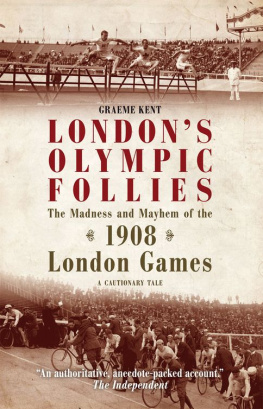

Published by SportsBooks Ltd

Copyright: Keith Baker

February 2008

This ebook edition first published in 2011

The right of Keith Baker to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

ISBN 9781907524288

Cover by Alan Hunns

This book is dedicated to those who made the 1908 Olympic Games possible and to those who took part in them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

One hundred years ago, with barely two years notice, London staged the Games that were to revitalise the Olympics of the modern era. The spectacle they provided, and their dramatic events, continue to attract the interest and imagination not only of sports scholars and writers, but of ordinary sports fans throughout the world. In writing this book I have been greatly helped by the large amount of published material contributed over the years by innumerable writers, statisticians, newspaper reporters and others on the Olympic movement and on the London Games of 1908 in particular. I owe a general debt of gratitude to them all, but especially to Theodore Cooks meticulous Official Report, and to Bill Mallons and Ian Buchanans masterly publication on the events of the 1908 Games, both of which have proved invaluable sources of reference.

I have been fortunate enough to live relatively near to the excellent British Library at Boston Spa and I am deeply grateful to the library staff there for their professionalism and friendliness with which they traced and provided material for me on countless occasions. Similarly, my thanks are due to staff at the Public Libraries in the cities of Sheffield and Oldham, to those at the Colindale Newspaper Library, and to the staff of the British Olympic Association. Without the help of all the above, this book would never have come to fruition. If in using any of the material provided any copyright has been infringed, the lapse has been wholly unintentional.

As regards individuals, I am particularly indebted to Rob Evans, Richard Ashdown, Deidre MacDonagh, David Price, Bernard Edge and Michael Stewart for their encouragement, support and advice, and for the personal information they provided for me on some of the heroes of the 1908 Games. Most of all, I owe more than can be ever repaid to my wife, Sarah, for her invaluable comments on the manuscript in draft and to her love and encouragement throughout the project.

INTRODUCTION

The Olympic Games have been rightly described as the Mount Everest of Sport. No other sporting event has more prestige or is given more publicity. Every four years young men and women representing virtually all the nations of the world come together to compete against one another in a great variety of sports.

The growth of the Games has been phenomenal. In 1896, when the first of the modern Olympics was held in Athens, there were only three hundred athletes from eleven countries. When the Olympics returned to Athens in 2004, some eleven thousand athletes competed from more than two hundred countries. Despite the cost of the Games, their commercialisation and razzmatazz, and the controversies that seem inevitably to surround them, the Olympics mean something special to people and are extraordinarily popular.

The lofty ideals, such as the promotion of harmony and goodwill and universal peace, with which the modern Olympics were launched more than one hundred years ago, may now have little resonance. But millions of people are drawn to the Games as a singularly human institution, a great and sometimes beautiful spectacle, where emotions run high and heroic deeds are played out before them.

The ancient Olympic Games are regarded as starting at Olympia, Greece in 776 BC and were discontinued in AD 393 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius the Great when he outlawed all Greeces religious landmarks and its pagan ceremonies. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, it was mainly through the vision, enthusiasm and efforts of a Frenchman named Baron de Coubertin that the Olympic movement was resurrected. He was able to promote enough interest in the idea for the first Olympiad of the modern era to be held in Athens in 1896. Before the Olympics came to London in 1908, three more Games were held, in Paris in 1900, St Louis in 1904, and the so-called intercalated or interim Games of Athens in 1906.

The opening ceremony of the 1896 Athens Games on Easter Sunday drew huge crowds. The Games could hardly be considered an international event since two-thirds of the competitors were Greek, together with a mere twenty-one Germans, nineteen Frenchman, fourteen Americans and eight Britons, together with a smattering of other nationalities.

The Greek spectators, hungry for success, grew more angry and frustrated as one event after another was won by the Americans. It was a Greek shepherd called Spyridon Loues who came to their rescue when he won the marathon. A devout man, he was said to have spent most of the previous evening in prayer and had fasted the entire day before the race.

The popular response to Loues victory, and the national celebrations which followed, were so great that they created just the momentum needed for the Olympic experiment to feel confident enough to move on to its next selected venue Paris.

Unfortunately, the Paris Games of 1900 were not a success. They took place over a period of two months, and since they were arranged as a peripheral part of a World Fair, they were hardly noticed by visitors. Athletes from twenty countries competed, but most of the competitors were said to have treated the Games as a huge joke. Competitions were held in dismal facilities and were poorly organised.

The track and field events were held in the Bois de Boulogne. Races took place on the grass because the French did not want to disfigure the grass with a cinder track. The discus and javelin throws got caught in the trees which the French refused to cut down. The swimmers and divers were compelled to compete in the polluted waters of the Seine. Swimming the river downstream, the Australian swimmer, Frederick Lane, was swept along so fast by the current that he smashed the official 200 metres record by thirteen seconds!

The 1904 Games held in St Louis, USA, were equally disappointing, and generally regarded as the worst in the history of the Olympic movement. They have been described as being bathed in nationalism, ethnocentrism, controversy, confusion, and bad taste. (Findling & Pelle Historical Dictionary of the Modern Olympic Movement). Faced with a transatlantic voyage and a 1,000 mile train ride, most Europeans decided not to attend what some suspected to be a wilderness settlement menaced by Indians. British journalists covering the event claimed later that their most abiding memory was that the sole fare on the menu was buffalo meat(Guttman The Olympics).

Only nine nations were represented and the Games turned out to be little more than a United States sports fixture. Americans won twenty-two out of the twenty-three track and field events. Once more, it was the marathon that provided the real excitement. The American athlete Fred Lorz thrilled the home crowd by finishing well ahead of anyone else in the race but the euphoria soon evaporated when he was disqualified for travelling part of the way on a truck.

Next page