To Harold and Sylvia Davis

&

Nathan and Sylvia Grosof

CONTENTS

To me, [the marathon] is more than a race. Its a very personal thinga sense of supreme well being. When youve trained for a race, youve brought the body God gave you to the finest attunement it can possibly know. Your muscles are strong. Your mind is clear and clean. You are conscious of the power of your heart and lungs. You can feel your blood flowing, the oxygen actually serving as fuel. In short you are really and truly living . Its a supreme feeling of perfection and closeness to the infinite I cant express very well, but this is the way I attain it and I hope I always can.

CLARENCE DEMAR , seven-time winner of the Boston Marathon

To write properly about the Olympic Games of the twentieth century is to write about almost everything in the twentieth century. About plastics and politics and racism and the demise of the rigid Bible morality and the rise of situation ethics. About avarice and airplanes and vitamin pills and chauvinism and free love and selling refrigerators on television and urban renewal and electricity.

WILLIAM OSCAR JOHNSON

INTRODUCTION

At the dawn of the twentieth century, mankind was getting into motion. Trains crisscrossed continents, ocean liners churned across the seas, subways burrowed underneath cities. The first generation of automobiles was arriving even as the Wright brothers were conquering the air. Flickering black-and-white images on a white screen were bringing entertainment to the masses.

The earliest practitioners of the marathon race, invented in 1896, introduced a different kind of motion. At a time when competitive runners rarely ventured past five miles, and at a time when knowledge of the human body was primitive, they were pioneers of endurance. They were seen as superhuman or crazed or both. They had to be in order to survive roads so dusty that their lungs were clogged; shoes so thin that mere slips of leather separated their bloodied feet from rocky, uneven surfaces; training methods so archaic as to invite permanent physical damage.

But they persevered to become, as Boston Marathon historian Tom Derderian put it, the explorers, test pilots and astronauts of their era, boldly running where none had run before, and, in their perceptions and the publics, risking their lives and future health to do it.

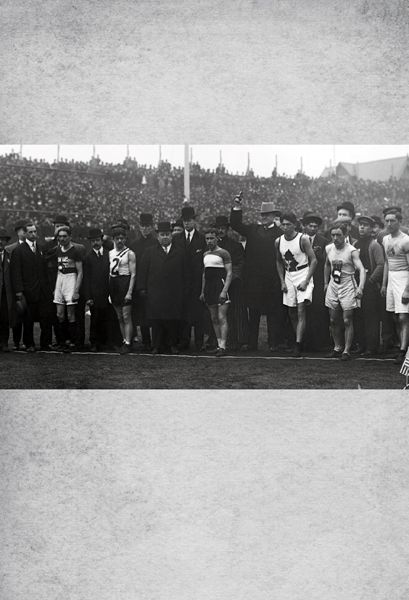

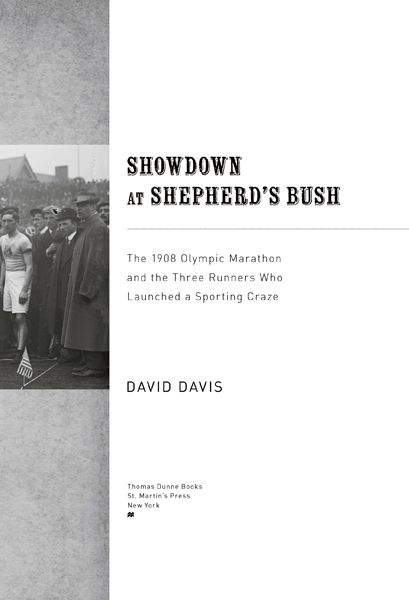

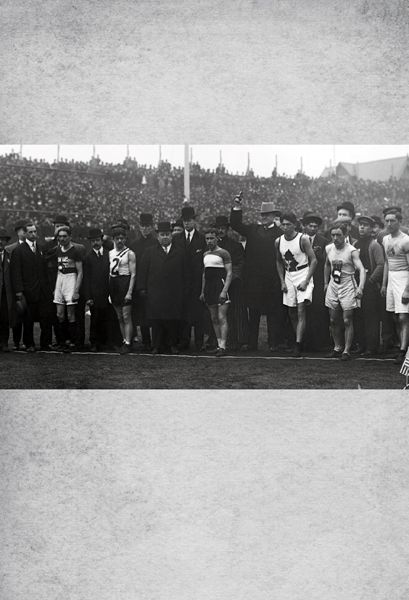

At the 1908 Olympics in London, when all of about fifty marathons had ever been raced, a man collapsed and almost died in front of 80,000 stunned spectators, including the Queen of England. The moment turned Dorando Pietri, from Italy, into one of the most famous athletes in the world and, after his recovery, one of the first celebrities to be known by a single name: Dorando.

Irving Berlin penned his first hit song about him, and Enrico Caruso sketched him. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle embraced him, while Mr. Dooley, the fictional barkeep invented by journalist Finley Peter Dunne, pontificated about him. Charles Dana Gibson, Ezra Pound, and F. S. Kelly wrote about him; Madison Square Garden sold out because of him.

Two of Dorandos opponents, Johnny Hayes and Tom Longboat, became equally famous. An Irish-American lad straight out of the tenements of New York City, Hayes was a Horatio Alger character sprung to life, championed by none other than President Theodore Roosevelt. Tom Longboats record-smashing victories and controversial losses made him the most legendary Canadian athlete until Wayne Gretzky came along (the two were born just miles apart). His athletic prowess afforded him mainstream respect, while his Native Indian heritage triggered hateful prejudice in and out of the sporting arena.

In the period before the start of World War I, the trio jump-started the first Marathon Mania. They raced each other (and other opponents) in arenas and stadiums across the United States, transforming the marathon into a crowd-pleasing spectacle and a legitimate athletic event. Along the way, they helped resurrect the flagging Olympic Movement and establish the standard distance for the marathon: 26 miles, 385 yards.

The exploits of Dorando, Hayes, and Longboat are largely forgotten today. But their legacy can be found in the exuberant spirit of contemporary marathoning, a global phenomenon that attracts elite athletes and weekend warriors alike, and one that inspires all of us to keep moving.

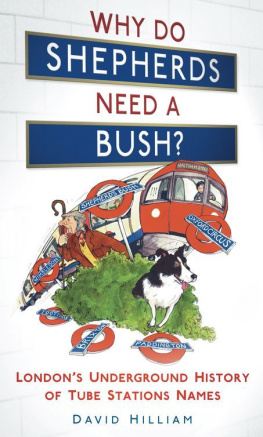

ONE

On the morning of July 24, 1908, the rains that had bedeviled the London Olympics surrendered to blue skies and a sodden heat. An excited hum disturbed the dawn as streams of Londoners exited the Wood Lane Underground station and hurried toward the Olympic Stadium as if drawn by hypnosis. The smart set chugged past in the newest, coolest toya motorized vehicle.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle stood in the press area of the Stadium, preparing to cover the days proceedings for the Daily Mail newspaper. On tap were wrestling and swimming finals, as well as the pole vault, but to Conan Doyle and the 80,000 spectators, reporters, Olympic officials, and royalty jammed inside the enormous sporting cathedral, as well as the tens of thousands of bystanders gathering along the twenty-five miles of roads leading to the Stadium, only one event mattered.

GREAT MARATHON RACE , read the headline in the Standard .

CROWNING EVENT OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES , the Graphic proclaimed.

Conan Doyle didnt require the deductive powers of Sherlock Holmes to understand what was at stake. The home team had endured a disastrous Olympics to this point. Foul weather led to poor attendance during the first week, and then the United Statess well-trained squad had stomped the Brits best on the track. Worse, their blustering Irish-American leader, James E. Sullivan, had whipped the press into hysterics by charging that the hosts were not behaving like honorable sportsmen.

To representatives of the British Empire, which prided itself as the birthplace of modern sports and the adjudicator of all matters concerning fair play and sportsmanship, this was the ultimate insult. Sullivan might as well have thumbed his nose at the Queen of England, who was, this very moment, journeying to the Stadium to observe the finish of the marathon.

Today was the last full day of what the press were calling The Battle of Shepherds Bush. The previous weeks humiliations and escapades would be forgotten and forgiven, Conan Doyle surmised, with a British victory in the marathon. Whats more, the pundits on both sides of the Atlantic favored the chances of the twelve-strong English team. If Alex Duncan and James Beale could repeat their magnificent showing in the April Trials, when they navigated over muddy roads and through freezing sleet on much the same course, the gold medal would be theirs. Victory by one of the lads from the territories, from Canada or South Africa, would suffice, Conan Doyle conceded, so long as the bloody Stars and Stripes didnt show on the flagpole again.

The sun penetrated Conan Doyles tweed suit, and he retreated into the shade. It was going to be a hot one.

* * *

Adjacent to the press area, a parade of Olympic officials, led by Pierre de Coubertin, was finding their seats. A diminutive man with a frothy, jet-black mustache that threatened to engulf his face, the baron should have been in his glory. He had almost single-handedly engineered the revival of the Olympics in 1896, giving the ancient Games an international twist. A confirmed Anglophile, Coubertin had entrusted the 1908 Olympics to London on short notice, after Rome was forced to bow out. The London Games lead organizer, Lord Desborough, had proved himself worthy, cutting a favorable deal to ensure the construction of the grand Stadiumthe first such structure to be built for the modern Gamesand attracting the worlds top athletes.

Next page