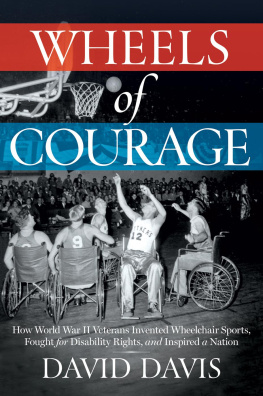

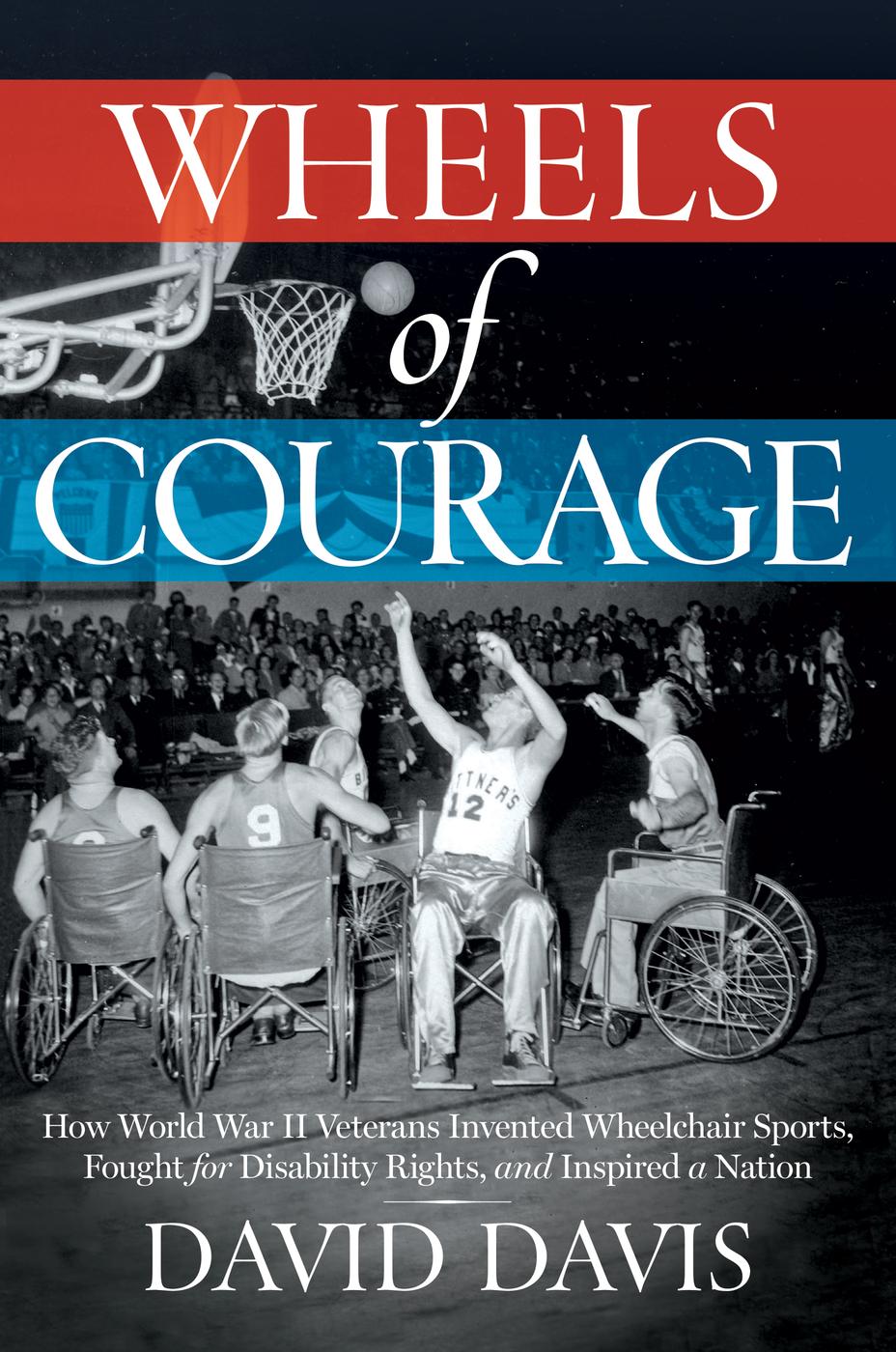

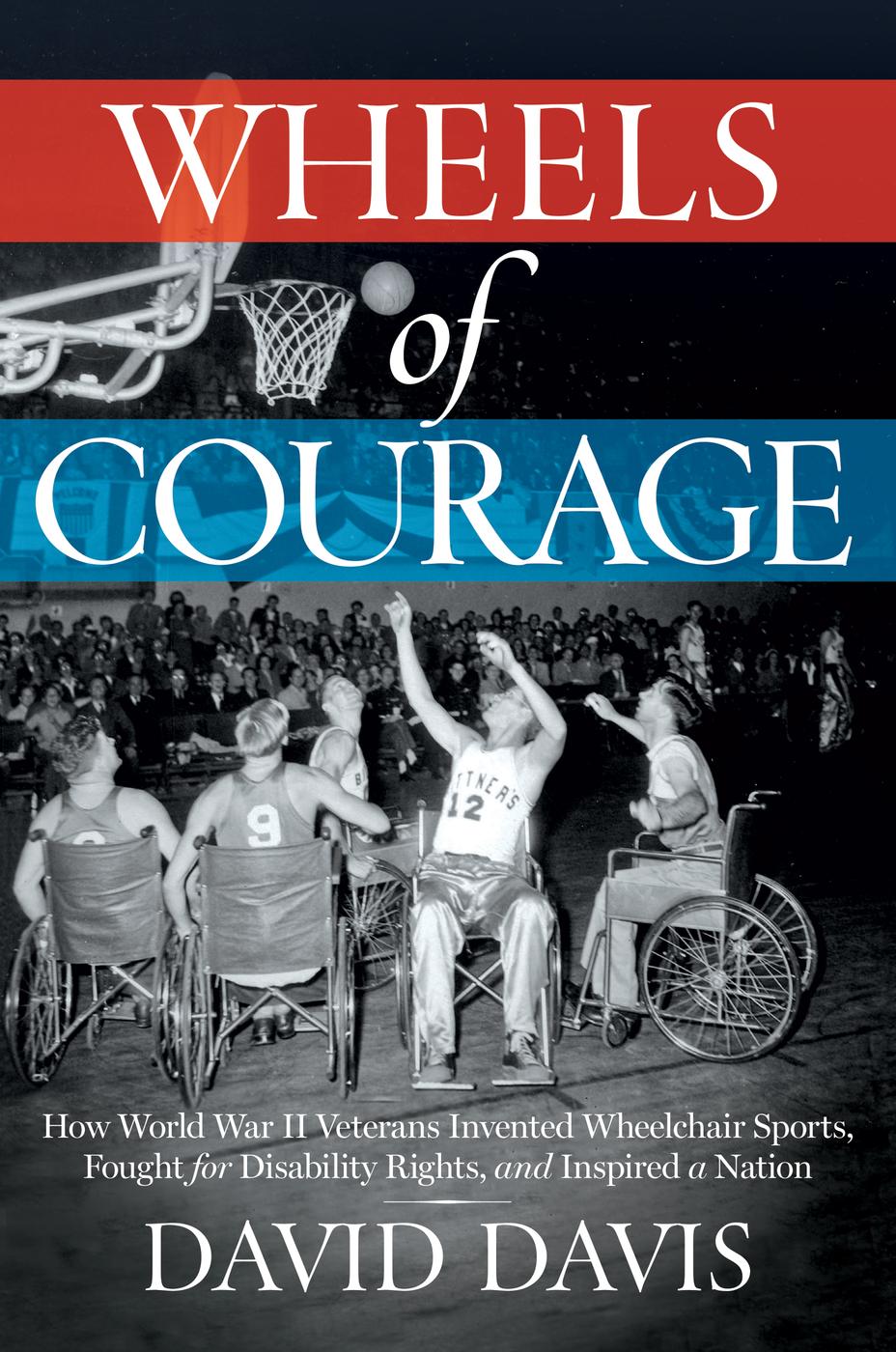

Copyright 2020 by David Davis

Jacket design by Edward A. Crawford. Jacket photography courtesy of John Winterholler Collection. Jacket copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Center Street

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

centerstreet.com

twitter.com/centerstreet

First Edition: August 2020

Center Street is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Center Street name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935798

ISBNs: 978-1-5460-8464-8 (hardcover), 978-1-5460-8462-4 (ebook)

E3-20200717-DA-NF-ORI

To Gene Jerry Fesenmeyer:

Thank you for sharing your story with me.

And to my sister, Margot Davis (19601986):

We miss you every day.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

March 10, 1948: A Wednesday evening in New York City. The illuminated marquee looming over the entrance to Madison Square Garden promotes the evenings featured attraction: BASKETBALL TONITE: KNICKS vs. ST. LOUIS BOMBERS.

Inside the worlds most famous entertainment palace, a haze of cigarette smoke hangs over the basketball court, empty save for two referees in black-and-white-striped shirts with whistles around their necks. A ring of loudspeakers hanging from the rafters burbles with the sonorous tones of public-address announcer John F. X. Condon as he notifies the assemblage that an exhibition game between two teams of World War II veterans will precede the main event.

What the near-capacity crowd of 15,561 spectators is about to witness is the most unusual form of basketball since 1891, when Dr. James Naismith invented the sport with a pair of peach baskets and a soccer ball.

World War II had ended nearly three years previous, but the war was still uppermost in the thoughts of many Americans. More than sixteen million men and womenabout 10 percent of the nations populationhad served in the U.S. Armed Forces during the war. American casualties (dead and wounded) totaled one million, a number that exceeded the population of all but five U.S. cities. Everybody knew somebody who had participated in the most destructive conflict in human history.

On the domestic front, the effort had been all-consuming. Americans bought war bonds, planted victory gardens, sent Red Cross parcels overseas to prisoners, rationed food and gasoline, conserved metal and paper, worked in munitions and aircraft factories, and memorized maps of the European and Pacific theaters. In the peace that followed, the publics interest in veterans issues remained as high as the nearby Empire State Building. Moviegoers flocked to view The Best Years of Our Lives, So Proudly We Hail!, and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo. Books about the war, from John Herseys Hiroshima to Norman Mailers The Naked and the Dead to James Gould Cozzenss Guard of Honor, were published to prize-winning acclaim.

The servicemen who took to the Garden hardwood that night were as extraordinarily ordinary as other veterans. They were the mud-rain-frost-and-wind boys that journalist Ernie Pyle celebrated in his Pulitzer Prizewinning columns from the front lines. They were Willie and Joe, as sketched by Bill Mauldin in his Pulitzer Prizewinning cartoons. They were your brother, your husband, your neighbor, your best friend from high school, your boss. They came from Paterson, New Jersey; Billings, Montana; Needham, Massachusetts; Brooklyn, New York; and the Boyle Heights section of Los Angeles. They were GI Joes and Dogfaces, Buck Privates and Mud Eaters, Leathernecks and Grunts.

Except these veterans were different. All of them were permanently paralyzed from the waist down from injuries theyd incurred during the war. All of them were seated in slender metal wheelchairs. The home team was made up of patients at Halloran General Hospital on Staten Island; the visitors traveled to New York from Cushing General Hospital in Framingham, Massachusetts.

When the game started, the chatter in the stands gave way to uneasy, muted murmuring. Hallorans Jack Gerhardt was speeding around the court like racecar driver Mauri Rose cornering at the Indianapolis 500 when he collided with another player and spilled out of his chair. Matrons gasped and dabbed at their eyes with handkerchiefs; crusty sportswriters complained that the smoke from their Lucky Strikes was causing them to tear up.

But after Gerhardt muscled his body back into his chair and demanded the ball, and after the Cushing crew brayed their displeasure at the officialsWhatsamatta, ref, cant you hear either?the mood inside the arena relaxed, and the fans began to cheer and whistle as if they were witnessing a miracle.

Which, in many respects, they were. For millennia, paraplegia had been a death sentence that physicians were powerless to prevent. The life expectancy of soldiers with traumatic spinal-cord injuries during World War I was estimated to be about one year. But now, the wonders of modern medicine were promising hope, and paralyzed veterans like Gerhardt, a wiry paratrooper wounded at Normandy, could envision a future.

How that future would unfold was less clear. People with severe disabilities were usually shunted off to institutions or hidden away in private homes. The barrier-plagued society accommodated only non-disabled people. There were no curb cutouts at the street corners of most American cities, no ramps leading to the entrances of office buildings. There were no handicapped parking spaces or kneeling buses, no homes with accessible toilets, showers, and doorways.

That myopia extended to sports. Prior to World War II, playing sports was out of bounds for those with crippled bodies, a common phrase from the era and one that encompassed amputees and polio patients. The Paralympics didnt exist. Neither did the Warrior Games or the Invictus Games. And, who in their right mind would consider racing the 26.2 miles of the Boston Marathon in a wheelchair?

It turned out that thousands did. From the paraplegia wards of far-flung army and navy hospitals came a radical experiment: wheelchair sports. What started out as a fun diversion within the rehabilitation process soon turned into something more: spirited competition, yes, but also an avenue toward an independent life, an affirmation of a future, a diminution of stigma.

When paralyzed veterans took wheelchair basketball out of hospital gymnasiums and into storied sports stadiums like Madison Square Garden, Boston Garden, Chicago Stadium, the Oakland Civic Auditorium, Los Angeless Pan-Pacific Auditorium, St. Louiss Kiel Auditorium, and the Palestra in Philadelphia, they showed that they were not going to hide their condition behind closed doors. Their skill and moxie stirred a large section of the nation and, most importantly, they educated doctors, politicians, the media, business owners, and the general public about the latent value of people with disabilities.