Campaign 96

Okinawa 1945

The last battle

Gordon L Rottman Illustrated by Howard Gerrard

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

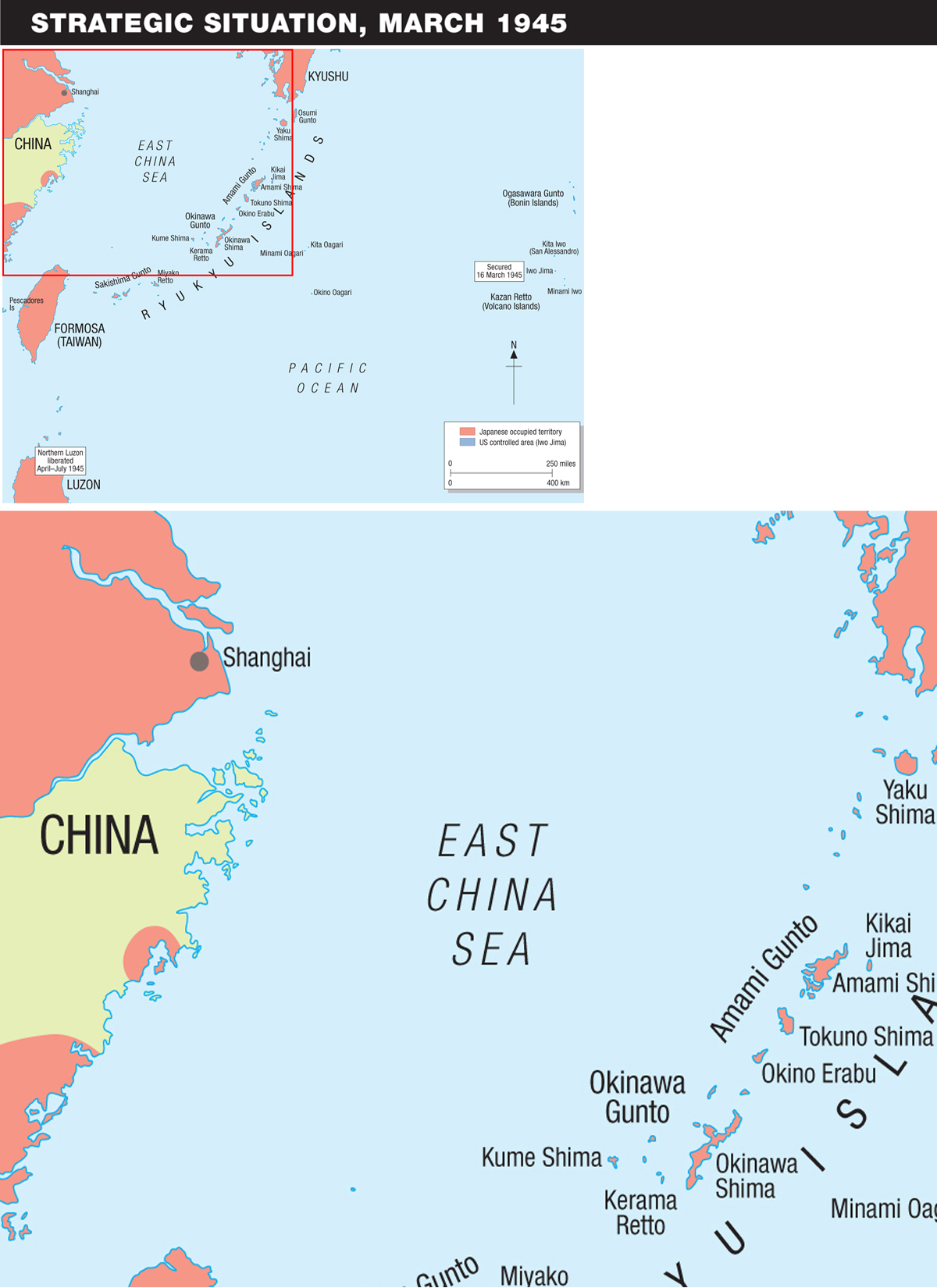

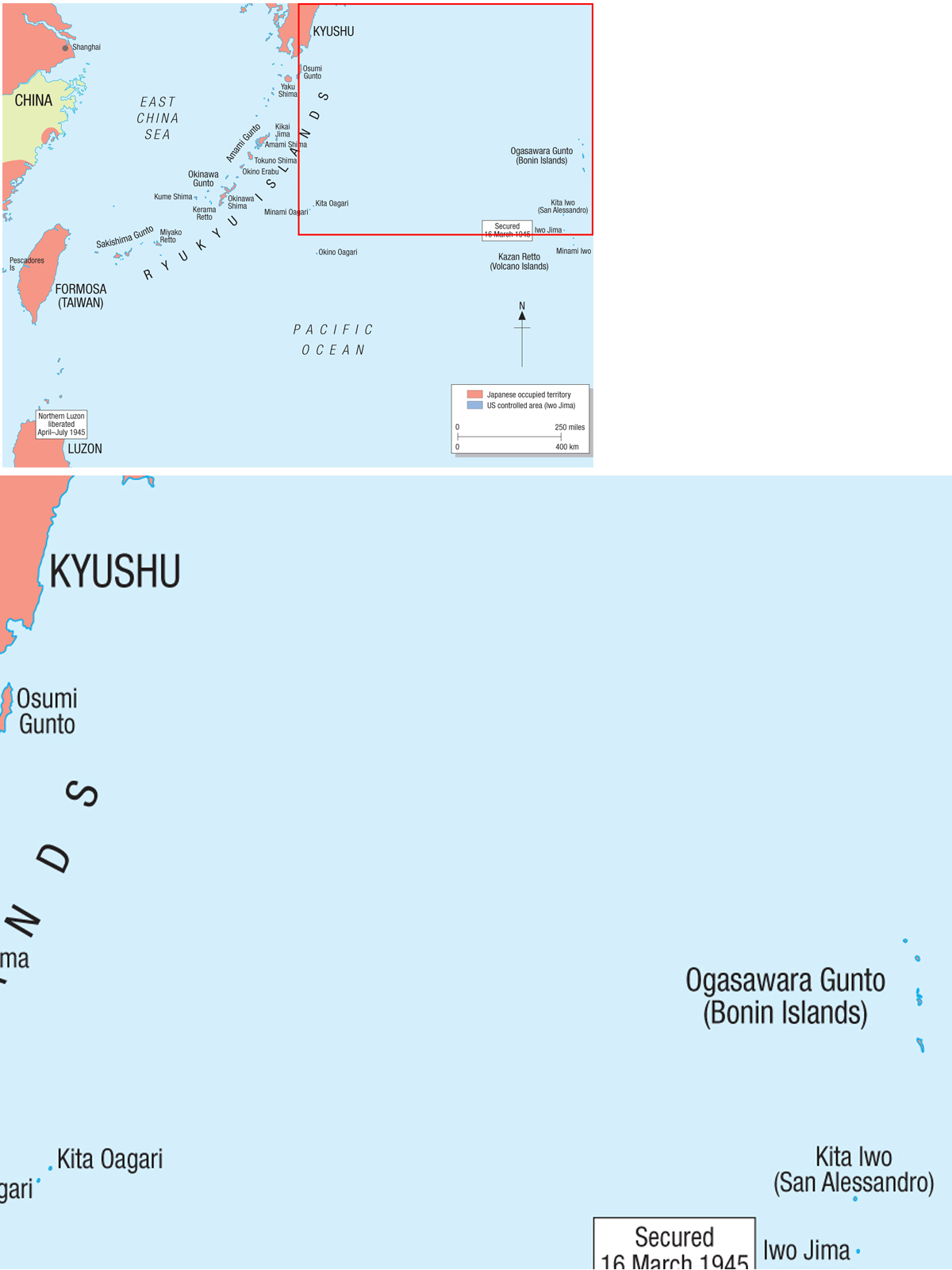

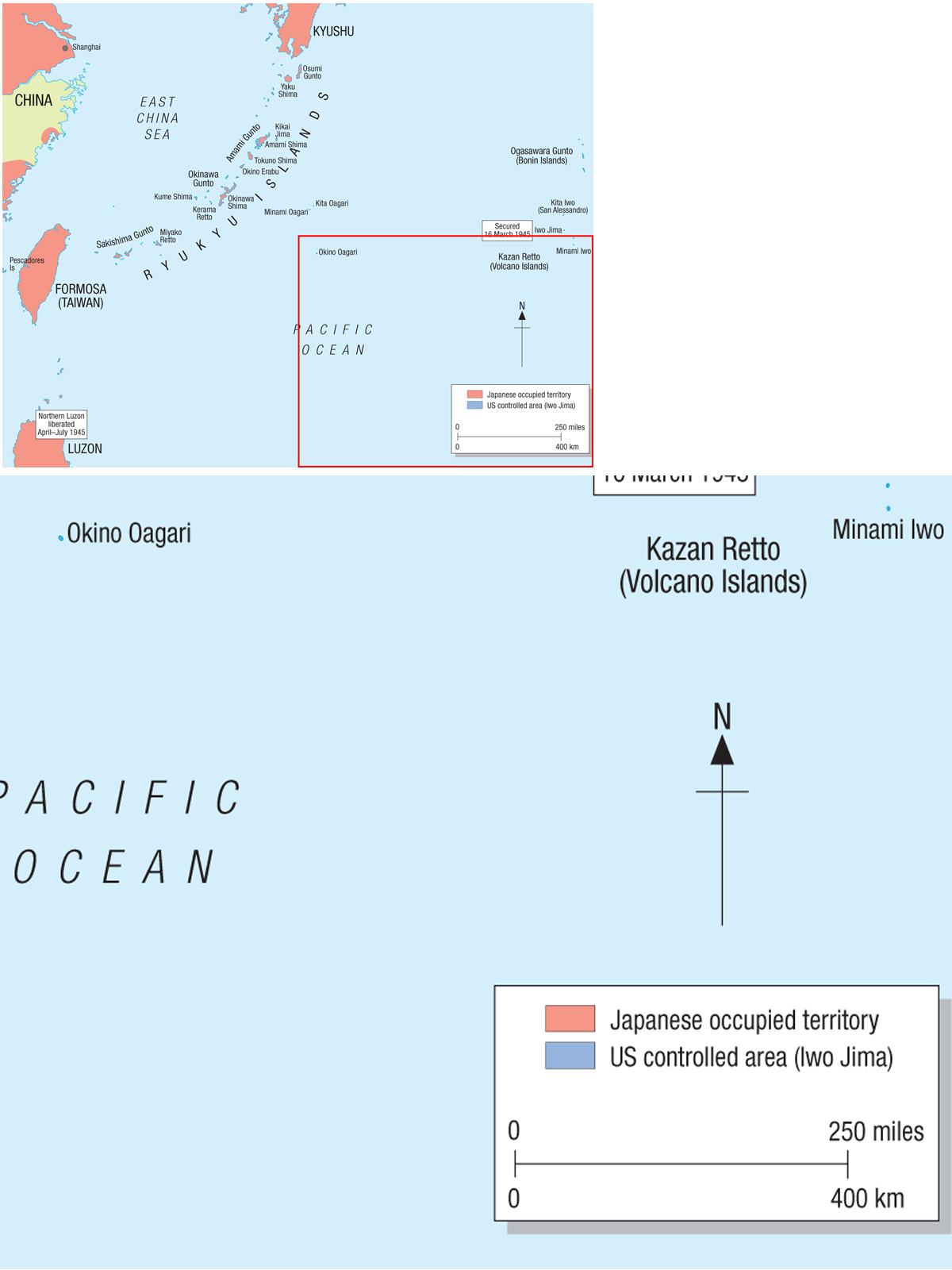

T he spring of 1945 found Allied fortunes in the Pacific very much in the ascendant. A series of victorious campaigns had reclaimed many of the islands and territories seized by the Imperial Japanese forces at the end of 1941 and the early months of 1942. The dark days of humiliating defeats were long behind the unstoppable Allied juggernaut. There was no doubt who would be the ultimate victor. The only questions remaining were when the final battle would be fought and how many more men would have to die to set right a grievous wrong.

Allied strategy entailed three thrusts across the Pacific. In the North Pacific Area the US Army and Navy, backed by Canadians, cleared the Japanese from Alaskas Aleutian Islands. In the Southwest Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur had at his disposal combined US Army, US Marine, Australian, and New Zealand forces with the Third and Seventh Fleets mainly supported by land-based aircraft. They first secured the line of communications between the US and Australia. Then they seized the Solomon Islands, with the main objective being Rabaul on New Britain, and thrust along New Guineas north coast aiming at the Philippines.

In the Central Pacific Area the Fifth Fleet, supported by carrier-based aircraft, secured the Gilberts in late 1943, with the ultimate objective being the Japanese base at Truk Atoll in the Carolines. The Japanese bastions at Rabaul and Truk were neutralized by air power and bypassed. The Fifth Fleet went on to seize the Marshalls in early 1944. The Fifth and Third Fleets next target was the Mariana Islands. The seizure of the Marianas proved to be an extremely serious blow to Japan. Part of the Mandated Territories bequeathed to Japan by the League of Nations in 1919, the former German possessions were considered part of the Japanese Empire. The fall of Saipan and neighboring Tinian in July 1944, followed by the liberation of Guam in August, led to such an outcry in Japan that General Shigenori Tojo was forced to resign as prime minister and a new cabinet was formed.

MacArthur invaded Leyte in the Philippines in October 1944 with the Sixth Army and Seventh Fleet. By the end of the year they had secured several solid footholds in the massive archipelago. The Philippines was finally declared liberated on 5 July 1945, two weeks after Okinawa was secured. In the meantime the Third Fleet took Iwo Jima between February and March 1945.

The Japanese knew what was coming next. What they did not know was exactly where the Americans would strike. The Imperial General Headquarters (IGHQ) narrowed the possible targets to Formosa off the Chinese mainland or Okinawa southwest of the Home Islands. The Japanese began to reinforce both areas as the American Fifth Fleet and Tenth Army marshaled at island bases across the Pacific.

An aerial view of Okinawa Shima looking north. The islands southern tip, Cape Kiyan, is cut off, but most of the south of the island, where the battle was largely fought out, is shown. (US Army)

A photograph of the Katchin Hanto (Peninsula) area on the east coast taken on 2 June 1945 shows the open areas encountered on much of southern Okinawa. (US Army)

PLANNING ICEBERG

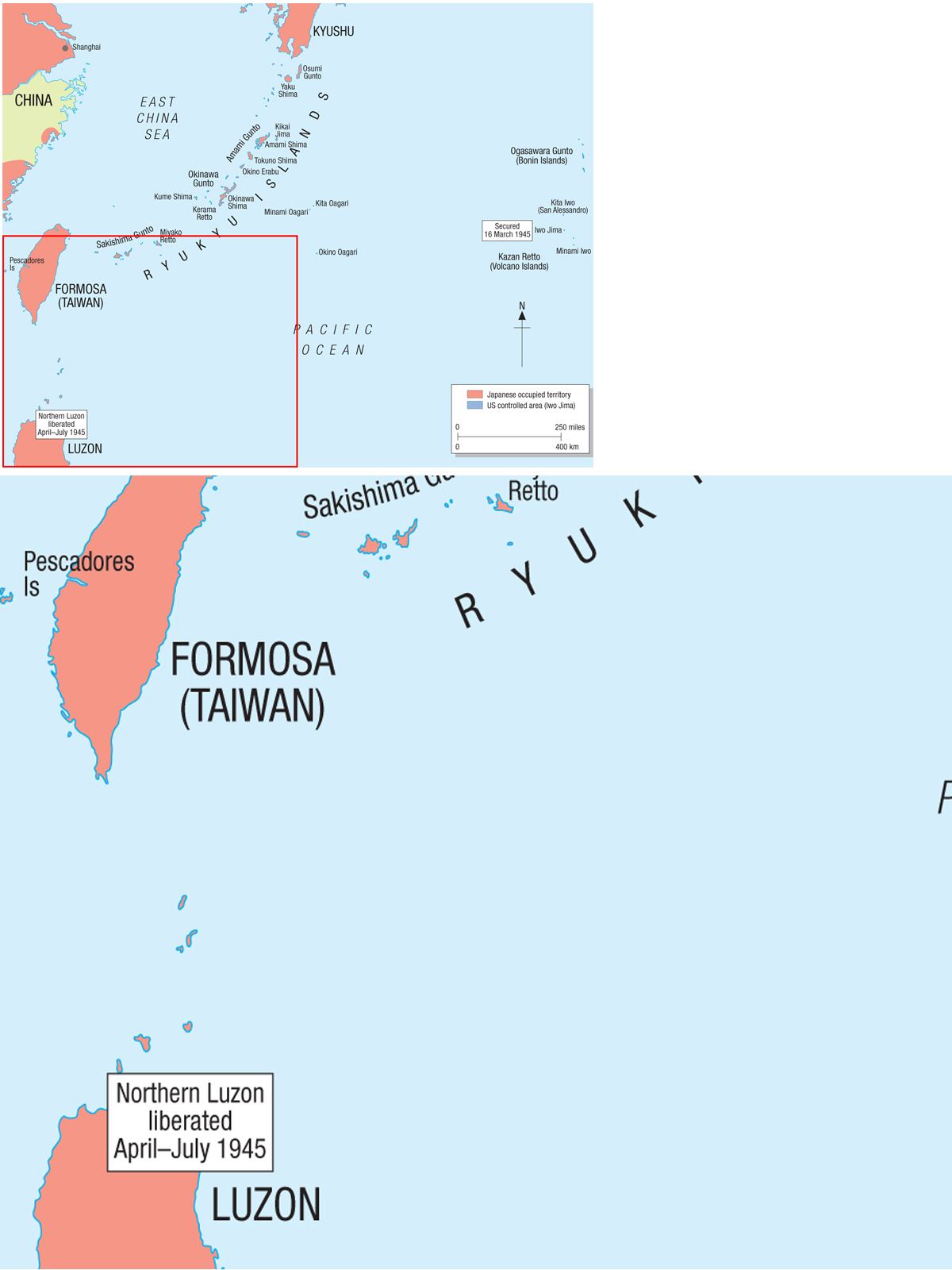

The battle for Okinawa is said by some to have begun in May 1944; a year before the landing. During the lull before the Marianas landings, Admiral Earnest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief, US Fleet, met with Admirals Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet/Commander, Pacific Ocean Area (CinCPAC/POA), and William F. Halsey, Commander, Third Fleet, in San Francisco to discuss future Pacific Theater strategy. A major concern was the possibility that Japan might conclude a separate peace with a hard-pressed China. Nimitz suggested establishing US positions on the coast of China and opening supply lines to the interior. Supplying the massive, but ill-equipped, Chinese Army would force Japan to reinforce the mainland and stretch its forces. Consideration was given to invading Formosa, 670 miles (1,079 km) southwest of Japan, before it could be reinforced, and thereby bypass the Philippines.

Formosa, basically a Japanese colony, had its advantages. Bypassing the Philippines would prevent a potentially protracted campaign requiring a massive commitment of US forces. Formosa would provide a base from which to invade the mainland, protect sea routes to China, and launch long-range bombers at Japan. B-29 Superfortresses of the Twentieth Air Force were operating out of southern China at extreme range and experiencing major difficulties receiving supplies and fuel from India.

Formosa could be a problem as well, however. It was well within range of Japanese air bases on mainland China, was garrisoned by substantial forces, could be easily reinforced from the mainland only 100 miles (161 km) away, and was a large mountainous land mass 240 miles (386 km) long and 90 miles (145 km) wide, with elevations to 13,000 ft (3,943 m). It promised to be a tough campaign; Formosa was about the size of Kyushu, the southernmost island of Japan.

In July 1944, with the Marianas campaign winding up, President Roosevelt met with Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur. Nimitz, as Commander, Pacific Ocean Area, controlled the South, Central, and North Pacific Areas from his headquarters at Pearl Harbor. MacArthur commanded forces coming out of Australia in the Southwest Pacific and New Guinea. He opposed the plan to bypass the Philippines contending that, with additional naval support, he had the forces to liberate them. Nimitz agreed to an alternate plan that included recapturing much of the Philippines between October and December 1944. Depending on the situation, either Luzon would be invaded in February 1945 or FormosaAmoy Area (on mainland China) in March. This would be followed by the Bonins (Chichi Jima) in April and the Ryukyus (with Okinawa) in May. MacArthur insisted on liberating Manila on Luzon, determined to fulfil the promise he made to return on his departure in March 1942.

Soon after the proposed plan was developed, Lieutenant-General Millard F. Harmon, Army Air Forces, Pacific Ocean Area, proposed that Operation Causeway Formosa be abandoned with compelling arguments that air operations could more effectively be conducted against Japan from the Marianas. He pointed out the threat posed by remaining hostile forces (it was not to be completely occupied because of its size), possible interception from the Chinese mainland along the entire route to Japan, and less favorable weather. Harmon proposed that Iwo Jima in the Volcano Islands (south of Japan) be seized in January 1945 and Okinawa (southwest of Japan) in June, simultaneous with the invasion of Luzon. General Robert C. Richardson, US Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Area, agreed with Harmon. Other key commanders tagged for

Next page