Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2010 by

CASEMATE

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

17 Cheap Street, Newbury RG14 5DD

Copyright Robin L. Rielly 2008

Paperback Edition ISBN 978-1-935149-41-5

Digital Edition ISBN 978-1-935149-91-0

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail: casemate@casematepublishing.com

Website www.casematepublishing.com

or

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01635) 231091, Fax (01635) 41619

E-mail: casemate-uk@casematepublishing.co.uk

Website www.casematepublishing.co.uk

To Emma Kaitlyn Rielly

Preface and Acknowledgments

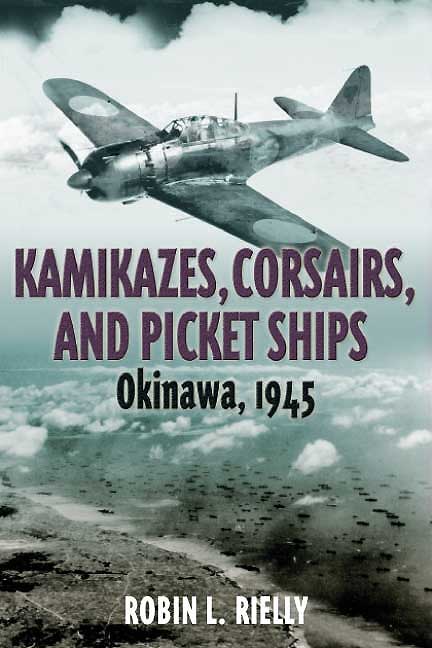

My initial interest in the ordeal of the radar picket ships at Okinawa was aroused during previous research on the LCS(L) gunboats in the Pacific theater. Many had served on the radar picket stations at Okinawa; however, the books about the battle for Okinawa hardly mentioned them. I began to realize that no historian had made a complete study of the radar picket ships ordeal at Okinawa. In the few works that touched upon the subject, destroyers were the focus of attention. With this in mind, I began a study to look further into the events surrounding the radar picket ships story.

As the project began, I had preconceived notions that the primary focus would be on the activities of the ships assigned to the radar picket stations. It soon became evident that there was another aspect to the ordeal, the flyers of the combat air patrols. At first the easiest and most obvious sources to find were those covering the activities of the navy and marine squadrons. After much research, occasional references to army air force planes began to show up, leading me down new paths. Within the first year of the study, the project had grown to include several classes of ships as well as the activities of navy, marine and army pilots as they worked in conjunction with the ships below them.

Since the fighting around the picket stations involved the kamikazes, it also seemed necessary to briefly describe their activities as well. Much of the informative material came from interrogations conducted by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, the Far Eastern Bureau of the British Ministry of Information, the Advanced Allied Translator and Interpreter Section, and the Military Intelligence Section of the General Headquarters Far East Command. The Japanese Monograph series was quite useful, providing information about various activities. As a result of the ULTRA program, numerous Japanese communications intercepted during the war were translated by American intelligence and are available as Magic Far East Summaries. In addition to supplying information about Japanese preparations and military movements, the summaries also helped to pinpoint the locations of various air units. Through these diffuse sources I have been able to write about the kamikazes activities as they relate to the picket ships.

Throughout the reports generated by American forces, as well as post-World War II literature, the kamikazes have continually been referred to as suicide pilots and I have used suicide throughout the text in order to keep some consistency in the writing. I do not, however, believe that this is an accurate descriptor for the actions of the men who flew special attack missions. When faced with the invasion of their country, these men were convinced by a militaristic government that the only way to save their homes and families was to use their aircraft, boats and other weapons in the most effective way, by crashing them into an American ship. Many did not believe their government to be correct in this assertion, but they did what men frequently do in combat, they followed orders and sacrificed themselves for their family, friends and country. This is quite different from committing suicide. I feel it important to make this distinction at the outset since I have, of necessity, quoted many reports describing their activities as suicidal. The Japanese themselves never considered these missions to be suicidal. They viewed the tactic as a special type of weapon borne of necessity. In spite of my disagreement with the term, it has been necessary to use that term continually as all of the official records contain it. Mixing terms would lead to confusion.

In an interview after the war, Lt. Gen. Masakazu Kawabe, who served as commanding general of the General Air Army noted:

You call our Kamikaze attacks suicide attacks. This is a misnomer and we feel very badly about your calling them suicide attacks. They were in no sense suicide. The pilot did not start out on his mission with the intention of committing suicide. He looked upon himself as a human bomb which would destroy a certain part of the enemy fleet for his country. They considered it a glorious thing, while suicide may not be so glorious.

To which his interrogator, Col. Ramsay D. Potts, replied, We call it suicide because we cannot find any other word in our vocabulary to describe those certain tactics.

Throughout the text, I have used the Allied code names for Japanese aircraft. The most famous of them was the Mitsubishi A6M5 Zero. However, all action reports filed by ships and aircraft squadrons use the allied code name of Zeke. To avoid confusion, I have used this code name throughout the text. Other aircraft are best known to Western readers by their code names. Japanese names are given in the western style, that is, surname first and family name last. Although it is not Japanese practice, it is more familiar to American readers. Ranks for individuals mentioned are contemporaneous with the event. Throughout the reports utilized in this work, times of the day have all been given in military time, i.e. 0-24 hours. In addition, all times are Item, which is Greenwich Mean Time minus 9 hours.

American ships have a class designator and hull number after their name. To make the text more readable, I have only included them in the full list of radar picket ships in the appendix. In a few cases I have included them for lesser known types of civilian ships or auxiliaries.

The overwhelming majority of the text is based on original source material, including unit war diaries, action reports, ship logs, interviews, correspondence, interrogations, and official documents. In many cases I have been able to access private diaries kept by men involved in the action as well as those who personally communicated their stories to me. A number of self-published books by participants have also been written, providing the reader with eye-witness accounts of the action.

I have tried to avoid a journalistic style in my writing; however, in order to understand the extent of the carnage on the radar picket stations it was sometimes necessary. Ship action reports do not describe the grisly aftermath of a kamikaze attack. In contrast there were torn limbs, decapitated bodies and terrible burns suffered by the men who experienced the kamikazes crash. By comparison, aircraft action reports frequently read as though they were written by journalists. In order to keep some semblance of continuity in writing style, I have attempted to bridge the gap between both writing styles in my own prose. In regard to the many quotes from action reports and other primary sources, I have not made any alterations to their text. In many cases the reports are terse, slang ridden, missing words, and not always grammatically correct, having been produced under conditions that might conservatively be described as difficult. The term for unidentified aircraft, bogeys, is frequently spelled as bogies in many of the official reports and the plural for various ships usually is spelled using an apostrophe s. In order to maintain accuracy, I have not altered the originals even though many are grammatically incorrect. I have also refrained from constantly inserting [sic] to indicate these errors in order to maintain readability. In a few instances it was necessary to insert a word to enhance clarity.