Conclusion

History does not repeat, but sometimes it rhymes.

MARK TWAIN

Lyrics have given voice to the Mexican experience even since the earliest eras ofthe conquest and colony. In 1604, Bernardo de Balbuenas voluminous poetic workGrandeza mexicana told the Empire of the lands riches and wealth. New Spain representeda utopian potential:

Mxico hermosura peregrina,

y altsimos ingenios de gran vuelo,

por fuerza de astroso virtud divina;

al fin, si es la beldad parte del cielo, | Beautiful pilgrim Mexico,

towering with geniuses in flight,

by the strength of starsor divine virtue;

finally if beauty is part of heaven, |

Mxico puede ser cielo del mundo,

pues cra la mahor que goza el suelo, | Mexico could be the worlds heaven,

for it breeds greatness in its soil, |

Oh ciudad rica, pueblo sin segundo,

ms lleno de tesoros y bellezas

que de pecesy arena el mar profundo! | Oh rich city, town second to none,

more full of treasures and beauties

than the deepsea has fish or sand! |

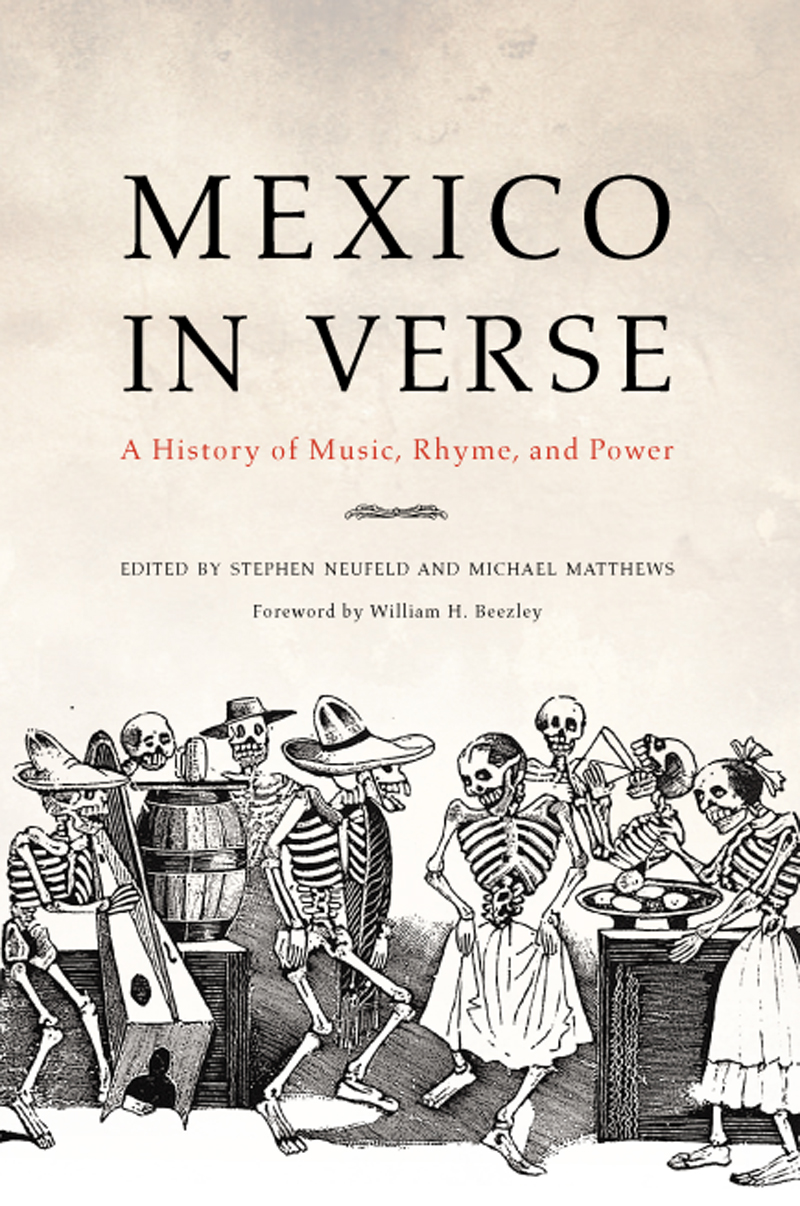

For centuries scholars took this work more or less at face value. Here, they asserted,was lyrical proof of colonial optimism, pride, and potential. Contemporaries knewbetter. Close interpretations of the political and social context of the time nowoffer us a different reading from the tradition of Balbuena as lauding greatness.The tract, it seems, reflected a deep and humorous satire of the disorder plaguingthe politics of the capital. Balbuena dedicated his work in its first edition toa notorious troublemaker, the Archbishop Francisco de Manso Zuega y Sola, and thesonnets thus spoke in double entendre to a distinct lack of order and good governance.Far from dismissing the work, this is precisely what should lend it weight for historiansseeking to learn about the roots of Mexican identity. Lyrical expression, powerfuland contextual, gives us a lens for seeing historical changes sometimes easy tomiss in broader political narratives.

Calling out leadership and making subtle attacks on too-comfortable elites, writersof verse showed that their works represented far more than empty vessels of language.Poets and songwriters worked inexorably to erode the bastions of hegemonic power.They eroded it with often nearly imperceptible challenges. Their words conjuredimages and sculpted memories among the broader populace. Ordinary masses had therebya discursive set of beliefs, symbols, and visions that, simply by existing, challengedthe narrower official narratives of the powerful. In these cultural productionsthey offered a counterhegemonic option for understanding society and events thatthey filled with popular aspirations and repetitions of favorite historical memories.At the same time, this was a slippery sort of collective memory. Highly contingenton place, performance, and audience, verses often expressed highly subject-specificmeanings. In other words, the interpretive nature of the genre made it highly personal,and matters of import to contemporaries may not always make sense to us now. Theysaw and heard verse from their perspective, not ours. As such, as with the Grandezamexicana, we should remember that any analyses of the lyrical past should be approachedwith humility and the awareness of deeper layers where oral and written verse hasshaped the national counternarrative of history.

The place of Mexican music and poetry, as our chapters illustrate, reveal that thenotion of lo mexicano shifted according to peoples subjectivities. Gender, class,race, religion, and location reshaped both the meaning and articulation of verse.Popular groups, policymakers, and cultural producersboth elite and commonunderstoodthe power of verse in articulating their own visions of truth, identity, and memory.Music and poetry were and are ubiquitous mediums that infuse and surround Mexicanslives. Yet scholars have tended to ignore those venues as epiphenomena to supposedlymore important economic and political structures. Indeed some scholars have trivializedthe value of examining cultural productions. Alan Knight and Stephen Haber have beentwo vociferous challengers to the so-called new cultural history. Alan Knight suggeststhat all history is cultural history and thus the label is meaningless. For Knight,defining culture as a system of signs and codes that produce meaning is too vague,making every historical study, in one way or another, cultural history.

Implicit in both critiques is that scholars should give up such attempts to exploresubjectivities and delve into the somehow more concrete genres of social, economic,and political approaches (as if those realms of investigation do not pose similarquandaries regarding the interpretation of documentary evidence). Whether studyingthe economic impact of railways on a country or the role played by peasants in revolution,ignoring the terms in which these events were understood by the less-literate peoplewho were affected or who participated leaves a significant historical void. The chaptersin this volume reject the defeatism inherent in Knight and Habers position. Insteadthey take up the (admittedly ambiguous and messy) challenge to explore how peopleimagined and understood the complex historical developments that played out in theirlives. Habers contention that due to its subjectivist epistemology cultural historyis fundamentally flawed in its ability to advance knowledge represents too narrowa view. Indeed, attempting to survey how people engaged and understood suchhistorical developments represents an ontological necessity in the formation andadvancement of knowledge. At times, we are forced to imagine the diverse waysthat people comprehended the complexity of economic, political, and social developmentsthat reshaped their experiences, yet we cannot imagine whatever we like.

Instead, as John Lewis Gaddis maintains, we must employ our experience, expertise,and intuition to do so, a process that involves heavy contextualization. Theseessays show that people interpreted broader issues of economic and political changethrough verse. Studies might tell us about the battles that militaries fought, theimpact of the railway on the economy, or that Catholic rebels opposed the secularizingpolicies of the state. Yet they do little in helping advance our understanding ofwhy men enrolled in the military and what that meant to them, or about how ordinarypeople viewed the arrival of the locomotive, or how Catholic rebels characterizedthe government that they took up arms against. Moreover, approaches that ignorethe cultural venues where people expressed their outlooks fail to provide insightsof the actors (aside from the elite) that drove history. This volume, humbly andrecognizing the difficulties and pitfalls inherent in such an endeavor, has soughtto provide these insights.

Beyond that, an exploration of the songs and poems recited and heard provides anunderstanding of the shifting social imaginary. While it is difficult to determinehow people received the lyrics that entered their lives, the essays here make knownthat the topics and issues that verses addressed found audiences with whom thosesubjects resonated. Music and poetry could introduce ordinary people to topics andpolitical agendas that they did not previously consider. At the same time, an analysisof music and poetry, at the very least, shows that socially and economically marginalizedgroups used verse to question and air their understandings of historical events and,in so doing, sought political incorporation and a more meaningful political voice.Elite groups and policymakers understood the power of verse and, as several chaptersdisclose, attempted to use such venues to shape the political values and consumptionpreferences of common people, often with mixed results.