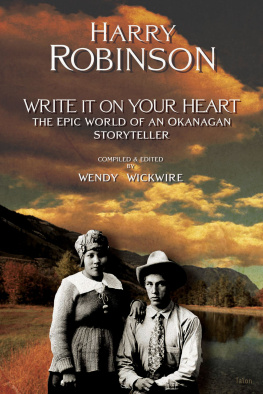

WRITE IT ON YOUR HEART

The Epic World of an Okanagan Storyteller Harry Robinson

Compiled and Edited by Wendy Wickwire

Copyright 1989 Harry Robinson and Wendy Wickwire Talonbooks

278 East 1st Avenue, Vancouver, BC, V5T 1A6

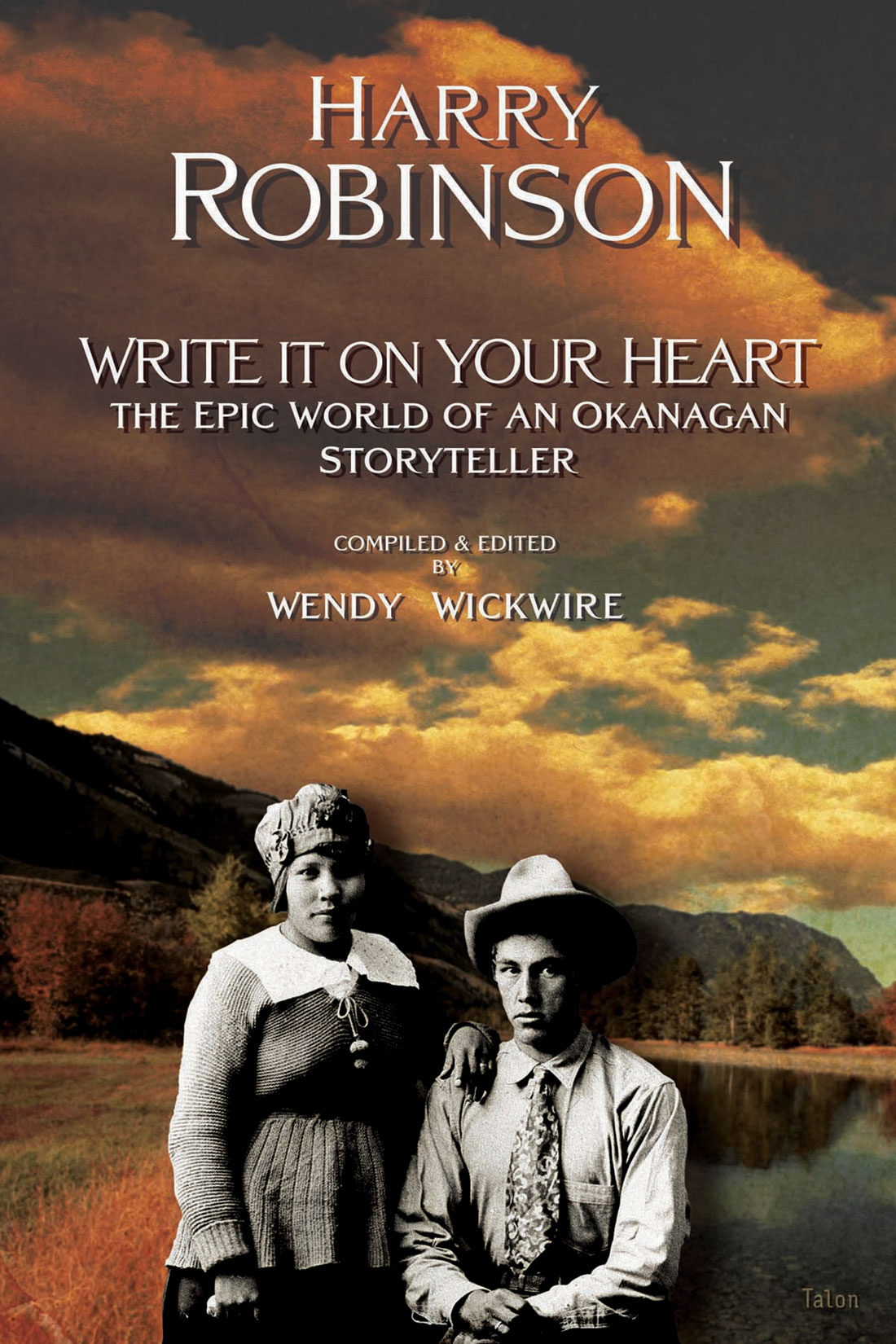

www.talonbooks.com On the cover: Harry Robinson with Margaret Holding, who taught him to read and write in English.

Photo courtesy of Harry Robinson.

Cover design by Adam Swica. Second Revised Printing: January 2006 No part of this book, covered by the copyright hereon, may be reproduced or used in any form or by any meansgraphic, electronic or mechanicalwithout prior permission of the publisher, except for excerpts in a review. Any request for photocopying of any part of this book shall be directed in writing to Access Copyright (The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5E 1E5; Tel: (416) 868-1620; Fax: (416) 868-1621. Some of these stories appeared in slightly different form in

Canadian FictionMagazine and

Whetstone. Unless otherwise stated, all photographs are by Robert Semeniuk. The photograph of Harry and Margaret Holding (1922), Harry and his dog (1927), and Harry and Matilda (1948) are courtesy of Harry Robinson.

To the Okanagan peopleCONTENTS

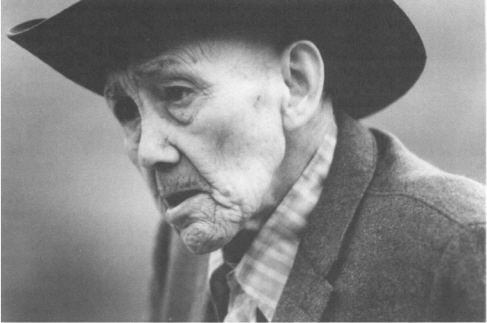

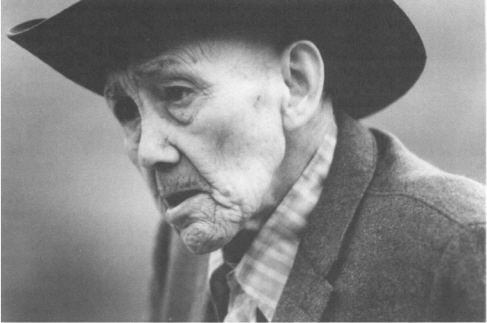

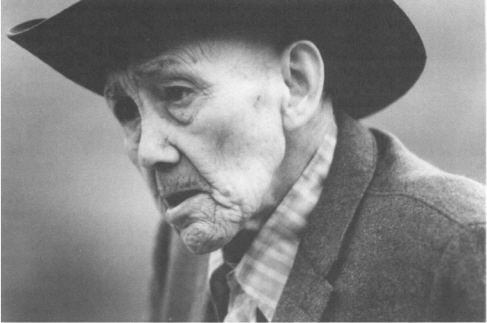

It was a blazing hot August afternoon when I first met Harry Robinson.

To the Okanagan peopleCONTENTS

It was a blazing hot August afternoon when I first met Harry Robinson.

It was the summer of 1977 and two friends had invited me to accompany them on a trip with Harry to the annual Omak rodeo in Washington State. He was very happy to see us when we arrived at his small house beside the highway near Hedley. As I was to discover was his custom, he invited us all to sit with him around the arborite table which stood prominently in the centre of his clean and ordered living room. While we were chatting during dinner, some element in the conversation suddenly prompted Harry to launch into a story. The story continued for several hours until well past midnight. The next day we all set off for Omak and the rodeo.

But this, my first experience of a true traditional storyteller has drawn me back to Harry again and again, year after year. In addition to his wealth of stories, many exciting and moving adventures were to followrodeos, sacred winter dances, and walks to his favourite mythological sites. Here in this quiet setting beside the Similkameen River in British Columbias southern interior, in a neat and simple house without television, radio or newspapers, Harry lives with an unbroken contact to a deep past. It has been a privilegeand a most enjoyable oneto spend time with him. THE MAKING OF A STORYTELLER Harry was born on October 8th, 1900 at Oyama, in the Okanagan Valley near Kelowna. Along with many other seasonal workers, his mother, Arcell Newhmkin and her parents had stopped there temporarily to earn some money digging and packing potatoes.

When the work was done, they moved on with their new baby to their home near Chopaka, in the Similkameen Valley near Keremeos. Members of the Lower Similkameen Indian Band, Harrys mother and her family were of full Okanagan ancestry. The Okanagan Indian reserves cover a huge territory, from the upper end of Okanagan Lake in the north, to Brewster, Washington in the south. Their language belongs to the Interior division of the Salishan language family. In south central British Columbia, this division also includes the Shuswap, Lillooet, and Thompson languages. The Similkameen Valley has not always been occupied by Okanagan-speaking people.

Research conducted in the late 1800s shows that an Athapaskan-speaking people, possibly related to the Chilcotin people in the north, once occupied this country as well as the Nicola Valley to the north. Exactly what these Similkameen-Nicola Athapaskans, as they have come to be known, were like and where they came from remains a mystery. As early as about 1700 they began to be absorbed by the Thompson and Okanagan-speaking peoples. By 1900 their language was nearly extinct and, by 1940 almost all memory of this culture was gone. In the Similkameen Valley today, only Okanagan is spoken and the most elderly natives acknowledge only that at one time the Similkameen language, not the Okanagan language, was spoken by the people who lived in this valley. Harrys father, Jimmie Robinson, was born in Ashnola in the Similkameen Valley, of an Okanagan mother and a Scottish father.

Arcell and Jimmie had parted ways before their son was born, so Harry spent his childhood years with Arcell and her parents, Louise and Joseph Newhmkin, at their small ranch near Chopaka. Louise was almost seventy years old and partially blind when her grandson was born. She had been raised in Brewster, south of the border, but had moved to Chopaka after her marriage in 1852. While Arcell worked to support the small family, Harry looked after his grandmother, and during their many hours together, she began to tell him stories which would later become the centre and meaning of his life: Somebodys got to be with her all the time. And when were together just by ourselves, she'd tell me, Come here! And I sit here while she hold me. And she'd tell me stories, kinda slow.

She wanted me to understand good. For all that time until I got to be big, she tell me stories. She tell me stories until she die in 1918 when she was eighty-five. Harrys storytelling circle was larger than just his grandmother. He speaks of others, including, for example, old Mary Narcisse, who was reputed to be 116 when she died in 1944, and John Ashnola, with whom Harry lived for almost a year when he was fourteen. Every night when I come in from working, he always tell me stories until late.

John Ashnola died in the 1918 flu epidemic at the age of ninety-eight. Other names figure prominently as well. Alex Skeuce, old Pierre, and old Christine, who was blind, are just some of the oldtimers who passed their stories on to Harry: I got enough people to tell me. Thats why I know. There was a small public school in Cawston, another village in the same area, and for five months, at the age of thirteen, Harry made the daily twelve-mile return trip to attend. But the trip was exhausting, and he soon stopped his public-school education.

Only later, when he was twenty-two, did he learn to read and write with the assistance of a friend, Margaret Holding. Ranching was the major way of life in the Similkameen Valley of Harrys youth and, to him, learning the skills of raising cattle was more important than acquiring a formal education. For his first job as a ranch-hand in January of 1917, he fed 580 head of cattle and 10 horses for two months. The following year, in March, he worked as a packer for a local sheep camp. That winter he fed the sheep (all 1800 of them) in addition to 80 head of cattle and 30 horses, staying on with the camp until 1919. That year, however, hearing that an older rancher, Bert Allison, needed workers, Harry went to him in search of a job and Allison placed him in charge of his hayfield.

It was a tough job. As Harry describes it, I piled sixteen to eighteen stacks of haythats about 400 tons. He stayed with Allison until 1920, and for the next few years he took on a variety of jobs, such as cutting wood near Summerland, clearing land, feeding stock, and baling hay. Finally, through marriage, Harry acquired his first ranch. The year was 1924, and he was working for a local rancher, Felix Johnny, breaking horses. Hearing that one of his mothers neighbours had died suddenly while bronco-riding, Harry took one of the horses and rode to the funeral.

![J K Rowling - Harry Potter [Complete Collection]](/uploads/posts/book/117015/thumbs/j-k-rowling-harry-potter-complete-collection.jpg)

Copyright 1989 Harry Robinson and Wendy Wickwire Talonbooks

Copyright 1989 Harry Robinson and Wendy Wickwire Talonbooks It was a blazing hot August afternoon when I first met Harry Robinson. To the Okanagan peopleCONTENTS

It was a blazing hot August afternoon when I first met Harry Robinson. To the Okanagan peopleCONTENTS