SPIRITUAL COMBAT REVISITED

Jonathan Robinson

of the Oratory

SPIRITUAL COMBAT

Revisited

This is indeed the hardest of all struggles;

for while we strive against self, self is striving against us,

and therefore is the victory here

most glorious and precious in the sight of God.

Lorenzo Scupoli, The Spiritual Combat

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover art: Crucifix with Christ and Saint Peter

Master of Saint Francis of Bardi (13th century)

Museo Bandini, Fiesole, Italy

Copyright Scala/Art Resource, New York

Cover design by Roxanne Mei Lum

2003 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 0-89870-930-x

Library of Congress Control Number 2002112863

Printed in the United States of America

To Joseph PopeIn remembrance of his unwearied and generous support of the Toronto Oratory and in gratitude for his many and unsung kindnesses to all of us in St. Philips House.

JR.

January 2002

CONTENTS

SPIRITUAL COMBAT

THE DEVELOPMENT OF PRAYER

WHAT IS VERY PLAIN

PROLOGUE

SPIRITUAL COMBAT TODAY

The function of grace, according to Augustine, is not to drag us kicking and screaming to salvation, but to allow us to want and to do the things that are right and in every sense desirable. For no one is just against his will. We shall want to do the right if we love the right, so that once we are prepared to love well, we shall need no manipulation, but simply Gods support to keep us going.

John M. Rist, Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized

It is a part of the unvarying tradition of the Church that there must be a continuing effort to bring the way we live into harmony with the demands of our faith. This effort involves a struggle with ourselves because we are divided creatures; we are pulled toward what is good, and we lean to what is evil. No one has ever written with more accuracy and pathos than Newman about our fallen human condition:

Oh, what a dreadful state, to have our desires one way, and our knowledge and conscience another; to have our life, our breath and food, upon the earth, and our eyes upon Him who died once and now liveth; to look upon Him who once was pierced, yet not to rise with Him and live with Him; to feel that a holy life is our only happiness, yet to have no heart to pursue it; to be certain that the wages of sin is death, yet to practise sin; to confess that the Angels alone are perfectly happy, for they do Gods will perfectly, yet to prepare ourselves for nothing else but the company of devils.

The struggle, or combat, to overcome these deep divisions in our nature and to bring our lives into harmony with the demands of our faith is called asceticism, and asceticism is an essential element of Christianity. Our desires must gradually be reordered so that we learn to want what Christ wants of us and to loathe in ourselves whatever stands in the way of our being united to his will. In its most general sense asceticism can be said to represent all those elements of the spiritual life that involve an organized campaign against the sinful aspects of the self, and against exterior temptation, as well as positive efforts directed toward the perfection of our own spiritual activities.

This book is about the theory and the practice of spiritual combat, or ascetical life, understood as the ordered effort to imitate Christ Jesus, and him crucified (1 Cor 2:2), and what the reader will find here is a discussion of asceticism as understood in the light of a tradition that stretches from the New Testament to our own day. The discussion has been undertaken within the theological framework of the Second Vatican Council and the Catechism of the Catholic Church . The fundamental lines of this tradition are constant: Asceticism is essential, but by itself it is not enough.

It may indeed have been the case that sometimes in the past the theory and practice of asceticism were badly understood, and imperfectly practiced, and this has provoked a reaction in favor of a less structured, less law-orientated Christianity. That is not to say that those who are unhappy about the way the ascetical life was taught and was practiced are advocating a sinful lifestyle or saying that the virtues do not matter. Nonetheless, they do want to contend that the ascetical life in the past had come to dominate most peoples conception of Christianity in a way that deformed the very notion of what being a Christian meant. They argue that the horizons of Christianity were reduced to a sort of unattractive, and largely irrelevant, obstacle race in which those who stayed the course without knocking over too many hurdles were assured of a prize in some future state. This misreading of the place of asceticism, they maintain, had especially deleterious effects in the life of prayer.

This perception, that the ascetical life had come to dominate the thinking and the practice of many Catholics to a disproportionate degree, is so widespread that it cannot be ignored. Nonetheless, however imperfectly understood or practiced, the conviction that Christianity demanded an effort to fight personal sin and to develop virtues such as kindness, patience, truth-telling, and chastity was and remains a valid one. It is true that spiritual combat is not an end in itself but is undertaken to work for perfection, purity of heart, or charity, and to lose sight of this is to have a deformed picture of the Christian life. On the other hand, it does not follow from this that authentic Christianity can, or should try to, forget about the tradition of asceticism.

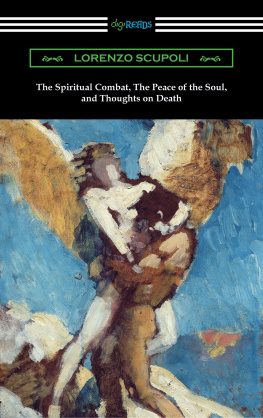

In order to provide the reader with a short and coherent statement of the elements of this tradition, I have followed the structure of one of the classics of ascetical theology, The Spiritual Combat , by Lorenzo Scupoli (1530-1610). On the other hand, his book is extremely condensed and presupposes a theological and moral outlook that today has to be sketched in if the contemporary reader is to benefit from its teaching. My own book spells out the elements of these moral and theological presuppositions.

Spiritual Combat Revisited should be understood, first of all, as an invitation to every reader to recognize the necessity of a spiritual combat in serious Christian living as well as a discussion of the weapons to be used in this warfare. At the same time, I would also like to think that my work might help to revive interest in one of the great spiritual classics of the ascetical life, that is, in Scupolis own book, The Spiritual Combat .

PART ONE

SPIRITUAL COMBAT

O let not your foot slip, or your eye be false, or your ear dull, or your attention flagging! Be not dispirited; be not afraid; keep a good heart; be bold; draw not back;you will be carried through. Whatever troubles come on you, of mind, body, or estate; from within or from without; from chance or from intent; from friends or foes;whatever your trouble be, though you be lonely, O children of a heavenly Father, be not afraid! quit you like men in your day; and when it is over, Christ will receive you to Himself, and your heart shall rejoice, and your joy no man taketh from you.

J. H. Newman, Warfare the Condition of Victory,

Parochial and Plain Sermons

In this part of Spiritual Combat Revisited the reader will find an analysis of the structure and some of the main arguments of Scupolis book. Before beginning this analysis, however, we should know something about the author himself and the circumstances under which The Spiritual Combat was written. In addition to this information, I have added a few lines on the sources of Scupolis work and on his influence.

Scupoli was born in Otranto (Italy) about 1530, and at the age of thirty-nine he was admitted to the Theatine Order, a community that was dedicated to the cultivation of the spiritual life, to preaching and teaching, and to the care of the sick and of prisoners. Scupoli, who had St. Andrew Avellino as his novice master for part of his novitiate, took his vows, was ordained a priest in 1577, and worked in Milan in a house of his order and then in Genoa. He was strict in the observance of his rule, constant in prayer, and a lover of solitude and silence. In 1585 there began a harsh ordeal and a long humiliation. By order of the general chapter of his order, he was sent to prison, deprived of the sacraments for a year, and reduced to the status of a lay brother. There is no evidence as to what he had done to merit this severe judgment, as, after a reconsideration of the verdict a year later, all the papers concerning the trial were burned. Whatever the cause may have been, Scupoli made no appeal, and it was not until April 1610, the year of his death, that he was once again allowed to take up his priestly ministry.

Next page