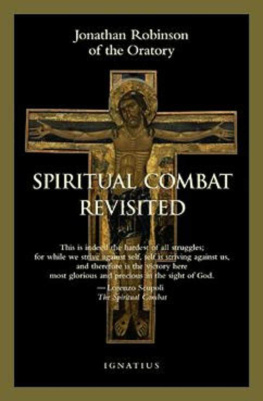

THE MASS AND MODERNITY

Jonathan Robinson

of the Oratory

The Mass and Modernity

Walking to Heaven Backward

We advance to the truth by experience of error; we succeed through failures. We know not how to do right except by having done wrong.... We know what is right, not positively, but negativelywe do not see the truth at once and make towards it, but we fall upon and try error, and find it is not the truth. We grope about by touch, not by sight, and so by a miserable experience exhaust the possible modes of acting till nought is left, but truth, remaining. Such is the process by which we succeed; we walk to heaven backward .

John Henry Newman,

Parochial and Plain Sermons

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover art:

Pietro Lorenzetti (c. 1306-1345)

The Last Supper , Fresco Lower Church, S. Francesco, Assisi, Italy

Scala / Art Resource, N.Y.

Cover design by Riz Boncan Morsella

2005 Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-069-1

ISBN 1-58617-069-4

Library of Congress Control Number 2005924112

FOR DAVID AND DEREK

SINE QUIBUS NON

CONTENTS

by the Very Reverend Ignatius Harrison, Superior of the London Oratory

PART ONE

The Enlightenment: Daring to Know

Latitudinarianism: Giving Up on Revelation

Kant and Moral Religion: Giving Up on the Church and the Sacraments

Hume and Atheism: Giving Up on God and Everlasting Life

Hegel: God Becomes the Community

Comte: Policing the Sublime

PART TWO

PostmodernismBlowing It All Up

The Church in Society

Swimming against the Tide

PART THREE

The Paschal Mystery

With Desire I Have Desired

From Communal Divinity to the Holy Community

Mr. Ryder Comes to Town

Know What You Are Doing

P REFACE

There is no shortage of books today that discuss the life of the Catholic Church in the modern world with a particular emphasis on the post-Vatican II liturgy. Often these writings shed more heat than light, sometimes because of their shrill tone and intemperate language or their indiscriminate dislike of anything modern. All too often they suffer from a markedly superficial analysis of the ideas behind the reforms. Sometimes we do find a more rigorously intellectual approach, but even that can be marred by an authors lack of practical or pastoral experience. The present volume by Fr. Robinson is notable for being the work of someone who is a pastoral priest, an experienced spiritual director, and a professional philosopher who has been a full-time member of the Department of Logic and Metaphysics at the University of Edinburgh and of the Department of Philosophy at McGill in Montreal. This is a rare combination and explains why this volume is so refreshing and illuminating. The author knows well what he is talking about, both in the theory and in the practice.

We find here a book that is friendly to the cause of post-Vatican II liturgical reform but also willing to question the usefulness of much that has been promoted in the name of that reform. We find here a circumspect critique of modernity based on the careful analysis of ideas and their cultural ramifications. There is, for example, an unusually attentive reading of Kants Religion within the Bounds of Reason Alone and Hegels philosophy of religion. We also find here an unwavering defense of the divine transcendence. This defense invokes the mystical writings of Dionysius the Areopagite and is preceded by a survey of recent sociological studies on secularization. Here the Southern writer and self-proclaimed hillbilly Thomist Flannery O Connor rubs shoulders with Iris Murdoch, the philosopher-novelist. Fr. Robinson speaks throughout with the voice of a working parish priest who is undaunted by the more impractical prescriptions of liturgical experts. He is a bold analytical thinker with an uncommon ability to cut through entrenched cant.

What will you not find in this book? The author endorses no familiar party line, nor does he seek to initiate a new party of his own. The modest liturgical reforms he does propose at the end of the book may appear radical to some, but that is a sure sign that they need to read the rest of the book. What we have here is a well-constructed working-kit for those who understand that any serious discussion of the modern liturgy must be based on sound philosophical and theological premises. I pray that this book might bring to the current liturgical wars an infusion of the authors own reasonableness, moderation, and reverent humilitythe humility with which he tackles the important liturgical question: What next?

I do not mean to suggest that this is a book without passion. No one who works his way through the following pages can doubt Fr. Robinsons passionate devotion to the sacred liturgy as the God-given means for the sanctification of mankind. He has the strong conviction that without the lure of the beauty of holiness as found in the liturgy, the Church has nothing substantial to offer the world. This conviction is what informs Fr. Robinsons dissection of the obstacles and opportunities of modernity in relation to the shibboleths and false turns of late twentieth-century liturgical reform.

A major influence on Fr. Robinsons insights has been his experience as founder of the Toronto Oratory and, subsequently, his many years as its superior and parish priest. Part of the Oratorian tradition, which, inspired largely by the English Oratory, he established in Canada, is a love of the Catholic Churchs public worship. The sixteenth-century founder of the Oratory in Rome, St. Philip Neri, knew that divine worship was an essential way of raising hearts and minds to God and, thus, changing lives for the better. Since its beginnings, the Oratory of St. Philip Neri has been known for the splendor of its liturgy. This love of the liturgy, always going hand in hand with a deep love of, and fidelity to, the Church, is something that the English Oratory has taken pains to maintain. This was a patrimony loyally transmitted by Newman and Faber from Rome to nineteenth-century England, and this patrimony was later fruitfully transplanted and has taken root in Canadas Toronto Oratory.

At times our critics have not hesitated to accuse us of being overly conservative or even obscurantist. I hope I can be forgiven for citing here just one true anecdote. One Sunday morning in the early 1980s, a bright young priest (and member of a distinguished religious order) stood outside the church of the London Oratory in South Kensington at about 12:15 P.M., watching several hundred of the faithful leaving the Oratory church after the solemn Latin Mass had ended. Later that week he said to me, I just cant understand why so many young people go to that eleven P.M. thing of yours. He asked himself, in a state of some perplexity, how it was that the hundreds of Mass attenders he had seen included a high proportion of people under thirty years of age. How was it that young families and young people could get anything out of a solemn Latin Mass ( Novus Ordo ), celebrated ad orientem , with polyphony and Gregorian chant? He could not understand why such a church and such a Mass were full. Indeed, he seemed to resent the fact. It seemed to him an aberration, a blot on the politically correct landscape of the liturgical establishment. I do not suggest that his question is easy to answer, beyond stating the obvious, that the crowds regularly attending such Masses clearly found something there to inspire and invigorate them. But if I had had Fr. Robinsons book to hand on that occasion, I would have been better able to steer this baffled and modern young cleric through the issues raised by his question and his prejudice.

I very much hope that this book becomes available to all those who do wonder what authentic worship is about and that it will help both clergy and laity to evaluate what they are doing when they approach the altar of sacrifice and how best to do it, for Gods greater glory and for the good of all his people.

Next page