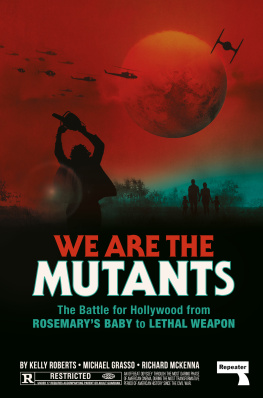

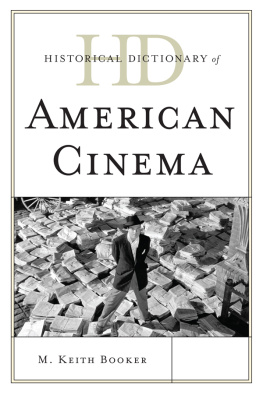

Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

Unit 11 Shepperton House

89-93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

United Kingdom

www.repeaterbooks.com

A Repeater Books paperback original 2022

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright Kelly Roberts, Michael Grasso and Richard McKenna 2022

Kelly Roberts, Michael Grasso and Richard McKenna assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

ISBN: 9781914420733

Ebook ISBN: 9781914420740

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books

PREFACE

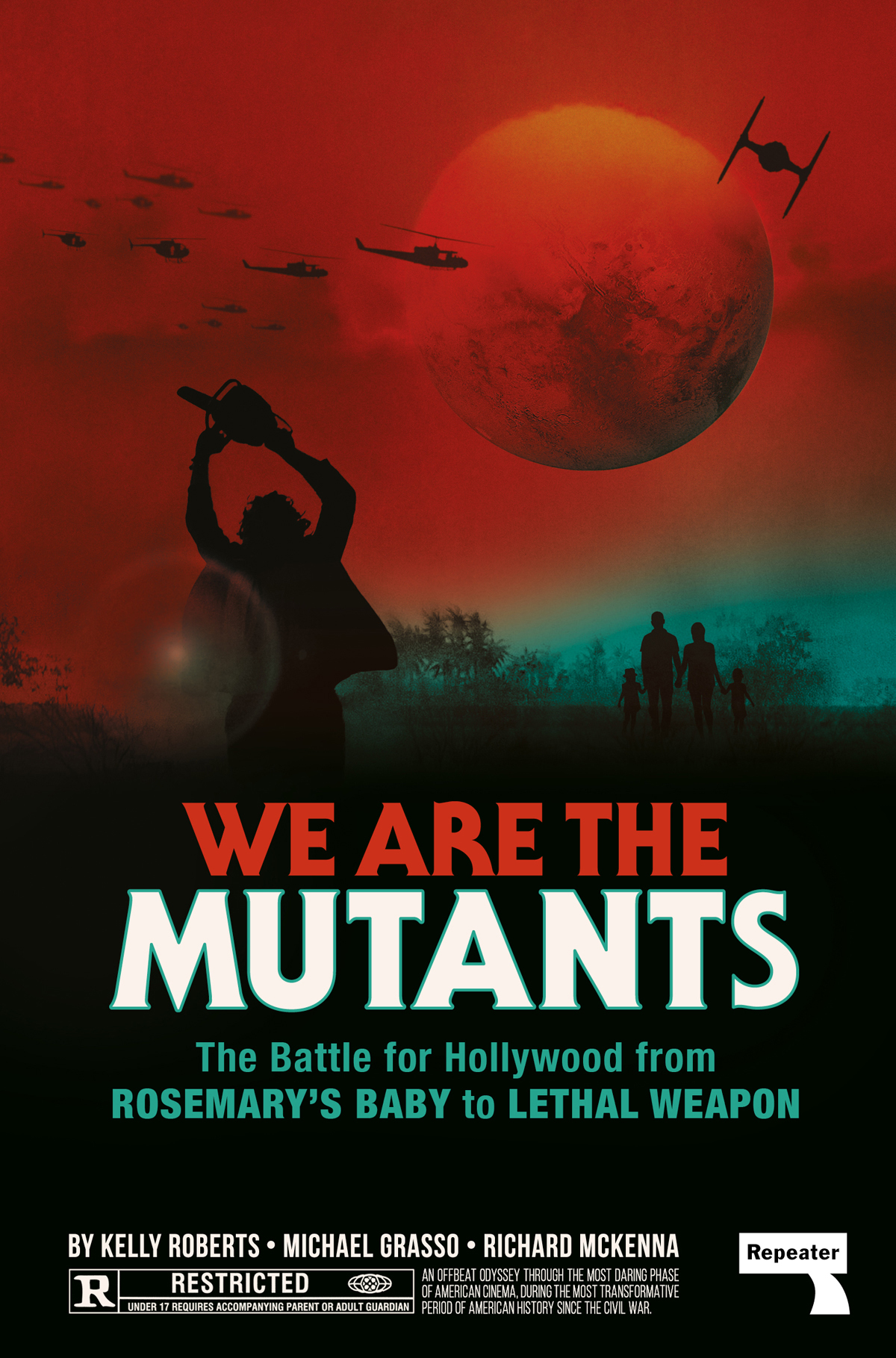

We Are the Mutants is a critical reassessment of what is arguably the most discussed and beloved stretch of movies in American history. Documenting the tumultuous and transformative years between the arrival of US combat troops in Vietnam and the end of President Ronald Reagans second term, weve chosen mostly to avoid the restrictive (and, if were being honest, overanalyzed) auteur cinema canon, focusing instead on an eclectic selection of films and filmmakers across multiple genreshorror, documentary, cinma vrit, disaster, vigilante action, neo-noir, post-apocalyptic sci-fithat together capture the push and pull of old and new Hollywood, New Deal and no deal America.

Each of our chapters pairs two films that at first glance may appear unrelated but ultimately intersect in meaningful and unexpected ways, both artistically and in the larger arenas of politics and culture. Weve focused on feature films because those are the ones that, intentionally or not, fairly or unfairly, best capture the beliefs, hopes, and anxieties of the audiences that paid to see them, as well as the realities and preoccupations of the day. Even though (and because) the national psyche was reeling from what Andreas Killen called the schizoid awareness that institutions were toppling and yet remained more firmly in place than ever, Americans always went to the movies, and in ever-increasing numbers. They went for new stories and old stories, for innovation and tradition, for engagement and escape. They went, and continue to go, because movies are how Americans choose to see the world.

We wrote this book during a global pandemic that, in the US at least, was made exponentially more catastrophic because of the ideological inheritance passed down by Richard Nixon and made permanent by Reagan: the idea that we must sacrifice our obligations to the community to enrich mercenary self-interest and protect individual liberty, even though liberty can only exist and be exercised within the context of community. The grueling and tragic events of the last two years (and how many more?) make any attempt to analyze the present moment just as urgent as it is futile. So well tell the story of how we got here instead.

INTRODUCTION

It was Theodore Roszak, a history professor at California State College at Hayward, who popularized the term counterculture and, in 1969, finally put into words the revolutionary impulse at its heart: a culture so radically disaffiliated from the mainstream assumptions of our society that it scarcely looks to many as a culture at all, but takes on the alarming appearance of a barbaric intrusion.

They were no such thing, of course, but they did radically shift those mainstream assumptionsabout youth, community, commerce, sexuality, authority, duty, recreation, ecology, media, artand they were an unprecedented generational phenomenon, especially through the eyes of their Depressionera parents. Born of postwar bounty and reared in the new suburbs, where the sorcerous glow of the first TV sets crossed the long shadow of the atomic bomb, literary critic Leslie Fiedler compared them not to barbarian invaders but to an alien civilization. Specifically invoking the language of science fiction, the only genre equipped to imagine the kinds of visionary transformations the young were chasing, he called them the new mutants: drop-outs from history

Spiro Agnew, poeticizing Richard Nixons gruff disdain, called them an effete corps of impudent snobs. read a defining passage of 1962s Port Huron Statementmost were apolitical or even anti-political: they were lifestyle consumers who wanted to rebrand themselves, not rebuild society. Others believed that the only way to become truly free was to remake their own minds, by means of psychedelic drugs, spiritual experience, or both. Their attitudes and behaviors and interests, subsumed under the expansive aegis of youth culture, sometimes overlapped and sometimes didnt.

Either way, it was not all peace signs and tambourines. During 1967s Summer of Love, the bohemian hippies poured into San Franciscos low-rent Haight-Ashbury district by the tens of thousands, picking all the flowers in Golden Gate Park and scattering trash and excrement along the Panhandle (the rats soon arrived). They also swamped the health and housing resources (clinics and hospitals were overrun with cases of overdose, venereal disease, and malnutrition) that already fell well short of meeting the needs of the areas poor and working-class residents, who only wanted ready access to the material security and middle-class comforts that had underwritten the countercultures great refusals in the first place. willfully uncoupled from the traditions and institutions of their forebears: addicts crumpled up on the floorboards, trust-funded runaways and burn-outs, black-caped paranoids, a tragically precocious five-year-old plied with LSD. Answers were not forthcoming.

As for the activist set, while hundreds of well-intentioned young whites temporarily abandoned their secure sinecures in Berkeley and Chicago and New York to volunteer for civil rights initiatives in the South, they had a habit of, in the words of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Chairman and Black Power vanguardist Stokely Carmichael, showing [Black people] how to do it.

It was obvious that dissenting white youth, whether acidheads or anarchists, in a sense wanted to become more Black than White,)

They were punished for their transgressions, though, this youthful opposition. They were beaten by the Hells Angels in 1965 on the Oakland-Berkeley border (the police, Hunter S. Thompson believed, moved aside to let the Angels do it).

It was as if the rod their parents had spared them in childhood (millions followed the nurturing, child-centric advice of pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock, who later became a vehement anti-war activist) was visited upon them a hundredfold for daring to talk back as young adults. What had they done to deserve such a punishment? They had mobilized against what history has proven to be an obscenely immoral war that three consecutive White Houses knew was unwinnable in every conventional sense. They rejected white supremacy, even if they did not always acknowledge white privilege. They denounced the genocidal stockpiling of nuclear weapons and demanded that the planet and all the life on it be nurtured. They made art in every medium that has always been revered and emulated. And yet, by the time Roszak put a name to their struggle, they had already lost: Richard Nixon was president, elected in 1968 by appealing, explicitly, to the forgotten Americans, the non-shouters and non-demonstrators. What future could there be in a nation that sanctioned the killing of its own children to sanctify the narcotic illusions of its elders?

Next page