Houghton Mifflin Company Boston

For Cathy and all others who have found their passion and not let go

Copyright 2000 by Nic Bishop

Map and diagram copyright 2000 by Houghton Mifflin Company

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bishop, Nic.

Digging for bird-dinosaurs : an expedition to Madagascar / Nic Bishop

p. cm.

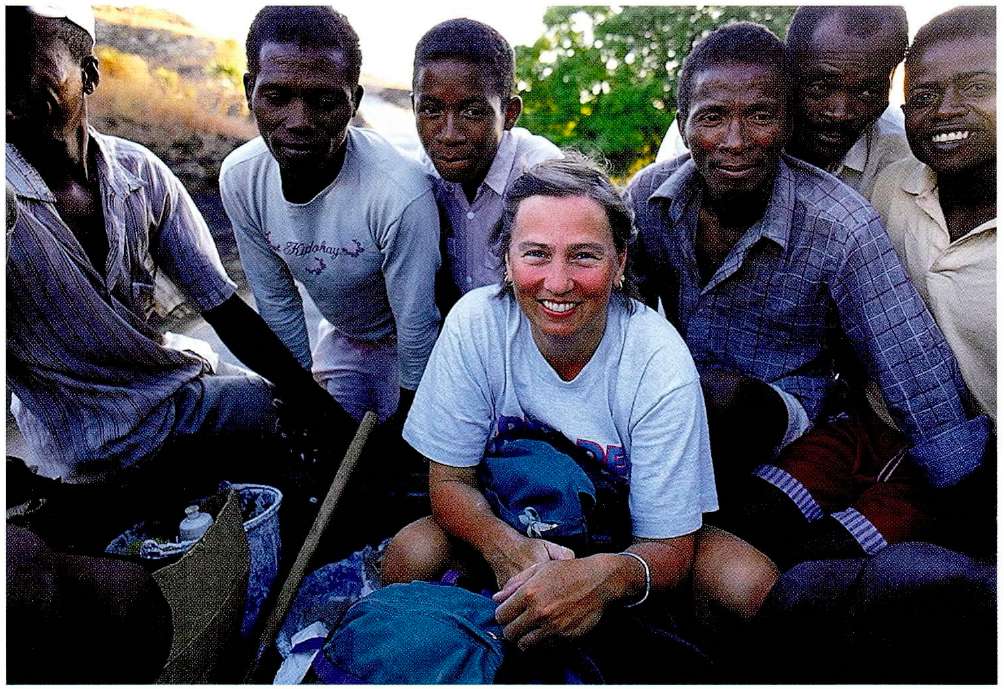

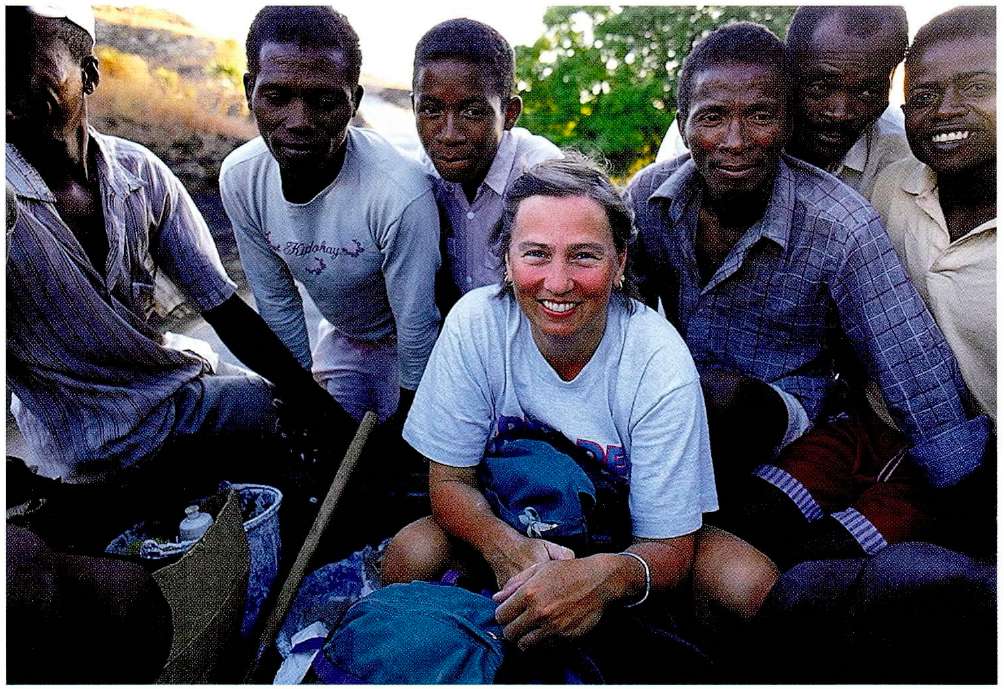

Summary: The story of Cathy Forster's experiences as a member of a team of paleontologists

who went on an expedition to the island of Madagascar in 1998 to search for fossil birds.

RNF ISBN 0-395-96056-8 PAP ISBN 0-618-19682-X

1. DinosaursMadagascarJuvenile literature. 2. Birds, FossilMadagascarJuvenile literature.

3. Forster, CathyJourneysMadagascar. [1. Dinosaurs-Madagascar 2.Birds, Fossil-Madagascar.

3. Forster, Cathy. 4. Madagascar.] I. Title.

QE862.D5B525 2000

567.9'09691dc21

99-36145

CIP

Printed in China

SCP 10 9 8 7 6 5

The Mystery of Bird-Dinosaurs

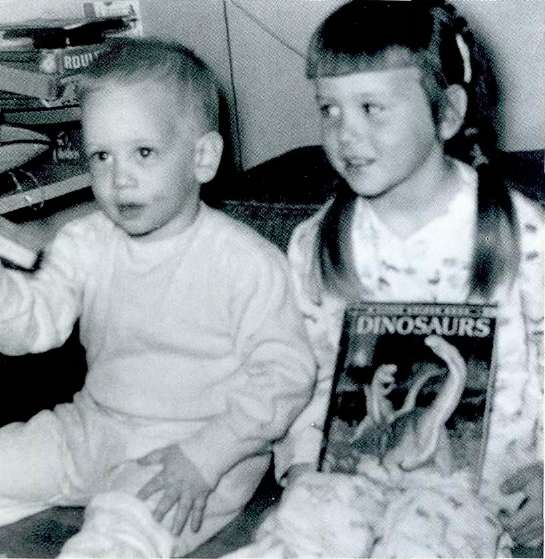

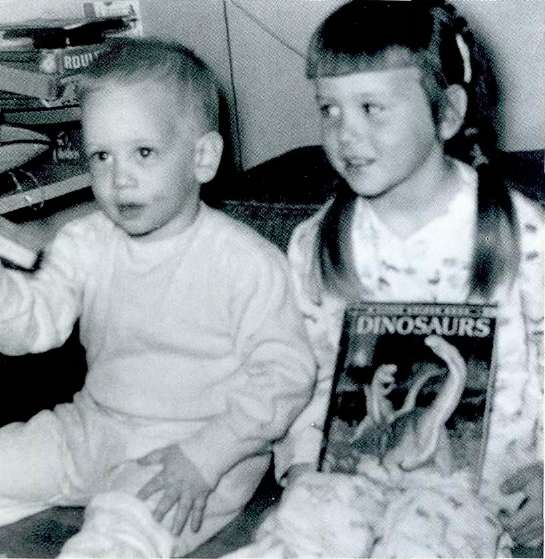

Cathy Forster was three years old when she first discovered dinosaurs. It was Christmas Day. As she opened one of her presents, out fell six of the strangest toy animals she had ever seen. Cathy was hooked even before her dad explained what they were.

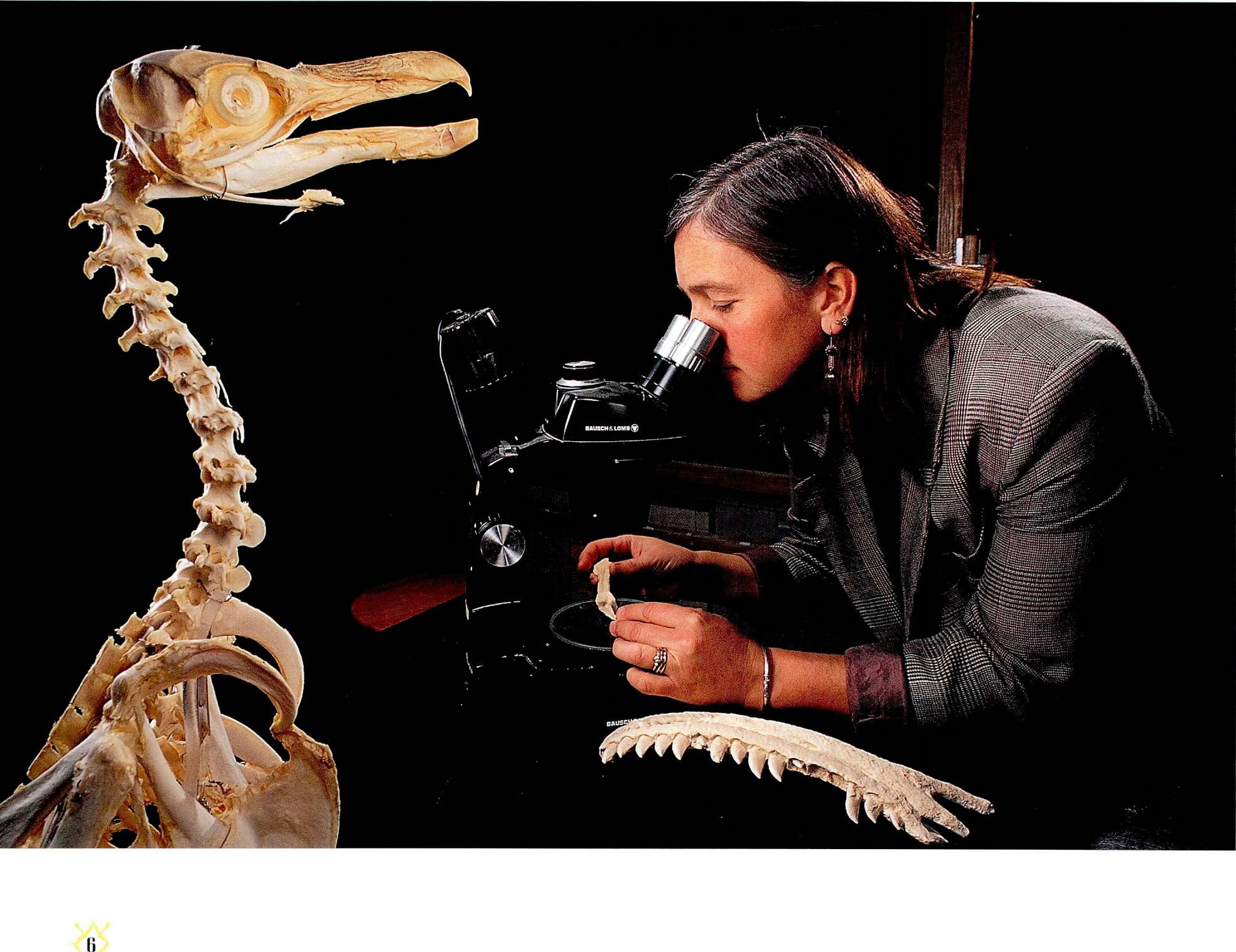

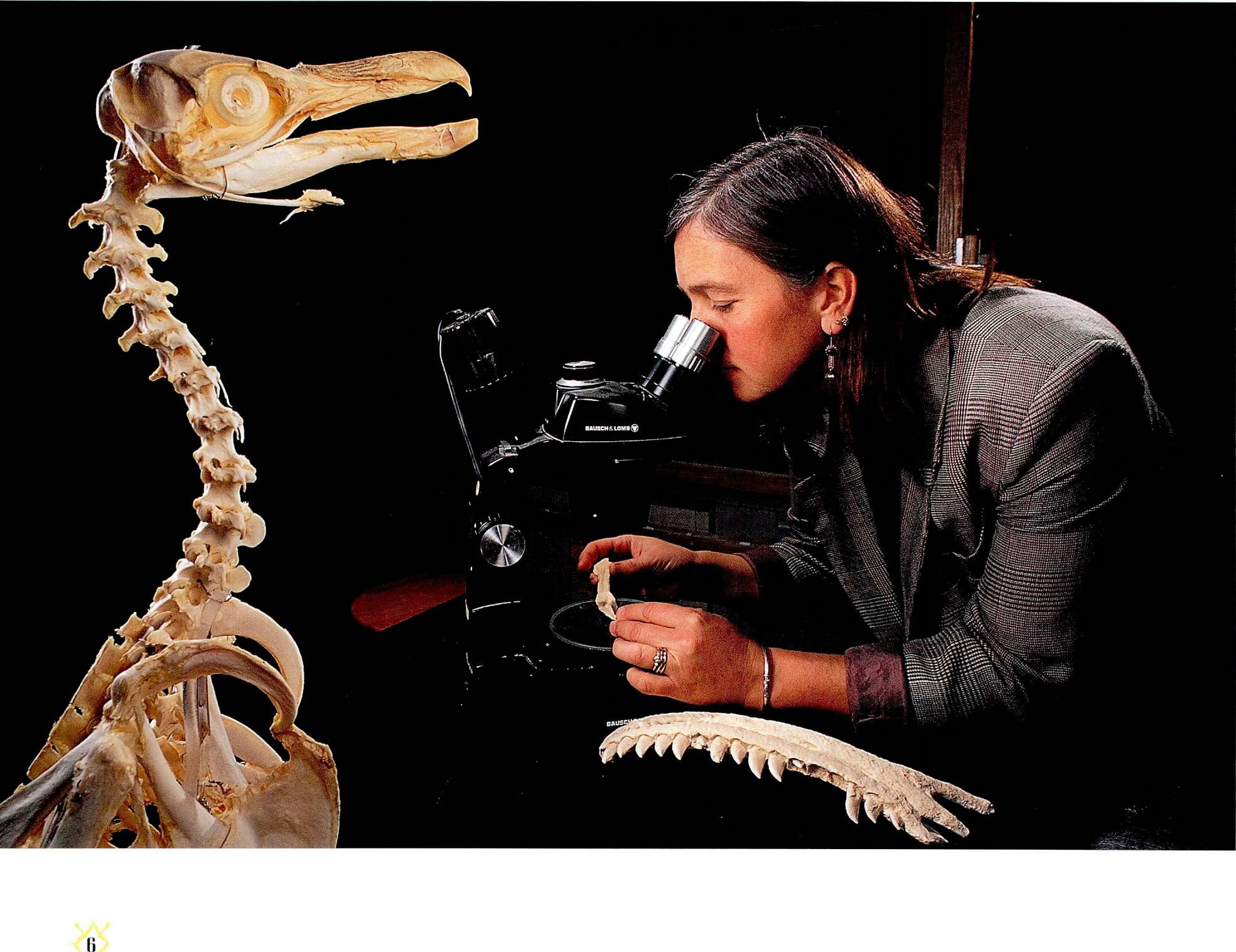

Now, as a paleontologist at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, discovering dinosaurs is Cathy's job. Her lab is filled with fossils from expeditions all over the world. The benches are covered with tyrannosaur teeth found in Montana, dinosaur skulls excavated in Madagascar, an iguanodon-tian from South Africa, and crocodile

photo John A. Forster

photo John A. Forster

Above: Cathy was fascinated by dinosaurs as a girl. Opposite: Cathy picks out two primitive bird-dinosaur bones from a drawer in her lab.

bones from Zimbabwe. Hundreds of other fossil bones are catalogued and carefully stored on shelves or in the cabinets that line the walls.

Cathy has loved to explore the outdoors and collect things ever since she was a little girl growing up in West St. Paul, Minnesota. On weekends and after school she would head to Mud Lake with her best friend, Nan. Together they climbed trees, caught turtles, or looked for snakes. "I filled my bedroom with things I found on my adventures," she recalls. "I had a butterfly collection, a shell collection, and a rock collection."

Whenever she had a chance, Cathy also collected fossils. "They were mostly fossil shellsthe sorts of things any young collector finds," she says. "My dad had studied biology in college, so he was always very patient with my interest in nature. It was just as well, since I often pestered my parents to take me to the science museum at St. Paul to see the dinosaurs. I loved to look at them all, but my favorite was a Triccratops, with three horns on its head. It was fabulous."

Much later, Cathy studied Triceratops for her doctoral degree at the University of Pennsylvania. Then after several years her curiosity turned toward other dinosaurs. Since coming to the State University of New York in 1994, Cathy has studied one of the greatest dinosaur mysteries of all: the evolution of birds.

People are fascinated by birds. We marvel at the magic of their flight and the extraordinary details of their wings and feathers. Birds are so different from other animals, it's natural to wonder how they evolved. What did their ancestors look like? What events led to the evolution of flight?

"We still don't know the answers to all these questions," Cathy says. "The biggest problem is that bird fossils are very rare. Their bones are so fine and fragile they tend to get broken up before they turn into fossils." As Cathy talks, she opens a special drawer in her lab. Inside are rows of small boxes filled with bones, some no larger than matchsticks. She picks out two bones and holds them gently, as if they were antique china. "These come from a very primitive bird that lived alongside the dinosaurs about 70 million years ago. We discovered it in Madagascar, and it's new to science."

Cathy believes that birds are closely related to dinosaurs. "If you study a modern bird skeleton you can find many things that are similar to dinosaurs," she says. "And if you look at primitive bird bones like these, it can be hard to tell them apart from dinosaur bones."

Many scientists go so far as to say that birds are a type of dinosaur. If this is true, then dinosaurs are not really extinct after all. Even though Tyrannosaurus, Triccratops, and most other dinosaurs died out, one group survivedthe birds. This idea sounds unbelievable at first. Do we really have feathered dinosaurs flying around the garden? But it does make some sense. Birds have scaly feet like dinosaurs, with three forward-pointing clawed toes and a hallux, a big toe that points backward. They lay eggs as dinosaurs do and, like some dinosaurs, they run on two legs.

Paleontologists first wondered about the link between birds and dinosaurs more than a hundred years ago. In the mid-nineteenth century some strange fossil animals were discovered in a limestone quarry in Germany. They had feathers like birds, but unlike any bird we know, their beaks had teeth and their wings had sharp claws. They also had the long bony tail of a reptile. They looked as much like dinosaurs as like birds. These creatures were named Archacoptcryx, from Greek

words meaning "ancient wing," and they were hailed as one of the most important scientific discoveries ever made. Scientists who studied Archaeopteryx started to think that birds must have evolved from dinosaurs.

But not everyone agreed. One paleontologist pointed out that one of Archaeopteryx's bones, called the collarbone or wishbone, was not found among dinosaurs, so they could not be related. In time, scientists began to believe that birds were not descended from dinosaurs after all but from some other reptile group that lived a lot earlier.

"In the end," says Cathy, "there really wasn't enough evidence to say one way or the other, and for a very long time no more fossil birds were found." Not only are fossil bird bones rare, but fossil impressions showing that an animal had feathers are even rarer. Yet without some feather impressions, it can be hard to recognize a fossil bird. For a long time, even museum experts mistook some Archaeopteryx specimens for dinosaurs because they lacked clear feather impressions.

But in the last twenty years, new evidence has come to light. Some dinosaurs have been discovered that have wishbones like birds. In China, paleontologists have made exciting finds of animals that appear to be feathered dinosaurs. One of Cathy's friends, Fernando Novas, found a two-legged dinosaur with birdlike limbs in Argentina. He called it

Next page

photo John A. Forster

photo John A. Forster