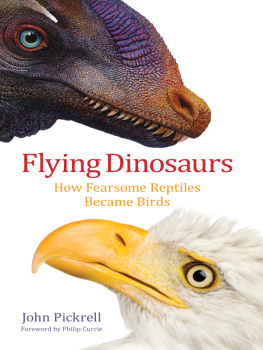

Flying Dinosaurs

Flying Dinosaurs

How Fearsome Reptiles

Became Birds

John Pickrell

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 John Pickrell

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53878-7

First published in Australia by NewSouth, an imprint of the University of New South Wales Press, Ltd.

ISBN 978-0-231-17178-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53878-7 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number : 2014938400

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Book design: Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design: Xou Creative

Front cover images: Feathered dinosaur Guanlong wucaii faces off against its modern relative and flying dinosaur, the bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). Guanlong is the earliest known tyrannosaur (Late Jurassic, 158163 million years ago) and one of the smallest members of the group at about 4 metres long. Top: Guanlong wucaii Peter Schouten, reproduced with permission. Bottom: Haliaeetus leucocephalus Eric Issele/iStock/Thinkstock.

Chapter opening image: The evolution of flightJeff Goertzen/Australian Geographic.

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

For my father

A great friend and inspiration

Contents

by Philip Currie

Towards the end of the twentieth century there was a flurry of publication of dinosaur books, so much so that even professional palaeontologists stopped noticing the new titles. It was therefore with genuine surprise that I read the book in your hands, because I was impressed by how many exciting discoveries have been made in the last decade or so, and how much we have learned about the biology of dinosaurs.

One area in particular the origin and diversification of birds has seen an astounding turnover of productive discovery and research. Yes, I was part of many of these discoveries, but its like watching a child grow up: you dont see the differences from week to week, but one day you are shocked to realise that your youngster is fully fledged!

One tends to think of palaeontology as a field where science marches forward at a slow and ponderous pace. However, the advances of the last decade and a half read like a science fiction novel as palaeontologists have embraced new and exciting technologies and approaches to learn things that Id never have thought possible when I started collecting dinosaurs professionally many decades ago.

For example, in the early 1990s who would have thought that many astoundingly well-preserved feathered dinosaur and bird skeletons would have been discovered in China and other parts of the world?

Profound thinking had predicted 20 years earlier that some dinosaurs should have been covered by feathers, and artists had even started drawing them with feathers in the 1970s. But the chance of finding preserved feathers in fossils seemed so remote that, even when I saw the first feathered dinosaur in 1996, I was trying to find other explanations for the halo of fuzz around Sinosauropteryx.

Now there are thousands of fossils of feathered dinosaurs and birds, from China, Mongolia, and other parts of the world. Even my own backyard, the province of Alberta in Canada, has now produced ornithomimids with feathers, and non-avian dinosaur feathers in amber. These discoveries should be exciting enough, but they have also opened up new areas of research on the origin of feathers, and the origin of powered flight in birds.

Studies of fossilised soft tissues have given us clues about growth, longevity and physiology. Stomach contents in the feathered dinosaurs have revealed diets that include fish, lizards, birds and mammals. The discovery of pigment-holding structures in feathers and skin has even revealed the colours and patterns of the feathered dinosaurs and early birds!

Thoroughly researched, with new interviews, this is one of the best, most accessible dinosaur books that has appeared in years.

Philip Currie, MSc, PhD, FRSC

Professor and Canada Research Chair, Dinosaur Palaeobiology University of Alberta

How I came to write this book.

Most palaeontologists will tell you they arrived in their job because, as a child, they loved prehistoric creatures, particularly dinosaurs. They just never grew up or at least they never stopped seeing a world filled with wonder and excitement. In that sense, I never grew up either. I never stopped being the little kid staring up in awe at the 32-metre-long fossil of Dippy the Diplodocus that fills the vaulted Central Hall of Londons Natural History Museum.

Ive long been in awe of the museum too, a grand cathedral to the natural world and Darwins theory of evolution by natural selection, all showcased in architect Alfred Waterhouses great neo-Romanesque confection of a building. The overall effect is one of Victorian grandeur, but with splendid detailing, right down to the gargoyles and statues of pterodactyls, cats, sabre-toothed lions, wolves, bears and numerous other creatures both prehistoric and modern.

After childhood visits to the museum helped nurture a passion for all things dinosaur, many roads in my early life led back to that imposing Victorian building in Londons leafy suburb of South Kensington. The offices where my dad had his business were just around the corner, so as a teen Id often pay visits, wandering the galleries or sitting out the front on the grass. When I started my degree in biology in 1996, I chose Imperial College, which lies right in the shadow of the museum.

While studying at Imperial, I spent some time volunteering in the museum press office. Then for my undergraduate project in my final year I spent a month in the mammal tower of the museum pulling out drawer after drawer of primate bones and measuring the skulls with calipers (my study didnt come to any strong conclusions about the evolution of primate body size as it was supposed to, but I drank in the opportunity to rummage through the museum collections). The next year I decided to take a masters degree at the museum itself, studying biodiversity, evolution and museum science.

Spending a year at the museum as a postgraduate was when I really grew to love the place. We had pretty much free rein behind the scenes, and I quickly came to realise that only a tiny fraction of the collections is on display. Most of the 70 million or so specimens (some of which were collected by Charles Darwin on the Beagle and by Joseph Banks, Captain Cooks botanist on the 176871 voyage of the Endeavour) are squirrelled away in climate-controlled corridors and towers that sprawl on and on, like a miniature campus. I spent many a productive afternoon exploring the bowels of this fantastic institution.

When my studies concluded, I chose not to pursue the academic route, instead becoming a science and environment journalist. This gave me the opportunity to remain involved with the field I loved, but allowed me to constantly learn new things in many different avenues of science. I never stopped following the latest dinosaur discoveries, and continued to write about them whenever I could some stories for National Geographic, others for New Scientist. But it was a feature story summarising all the many streams of evidence that birds are descended from dinosaurs, which appeared in Australias