RIDDLE OF THE FEATHERED DRAGONS

RIDDLE OF THE FEATHERED DRAGONS

Hidden Birds of China

Alan Feduccia

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2012 by Alan Feduccia.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (UK office).

Designed by Lindsey Voskowsky. Set in Fournier MT type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Feduccia, Alan.

Riddle of the feathered dragons : hidden birds of China /Alan Feduccia.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-16435-0 (hardback)

1. Birds, FossilChina. 2. BirdsEvolution. 3. Evolutionary paleobiology. I. Title.

QE871.F43 2012

568dc23 2011015862

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer (18991972), who cast a flood of light on the field of avian evolution

The truth is rarely pure and never simple.

Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Ideas on bird origins have been rapidly evolving since the great bonanza of Chinese Lower Cretaceous fossils began to be unearthed beginning in the early 1990s, so likewise the views expressed in this book metamorphosed in the hopes of conforming to the best explanations of the latest evidence; and therefore this book owes a debt to many people. For valuable discussion and input I thank David Burnham, Stephen Czerkas, Frietson Galis, Richard Hinchliffe, Lian-hai Hou, Frances James, Theagarten Lingham-Soliar, Paul Maderson, Larry Martin, Gerd Mller, Storrs Olson, John Pourtless, John Ruben, and Zhonghe Zhou. The entire manuscript was reviewed by Dominique Homberger, Lian-hai Hou, Frances James, and an anonymous paleontologist; and I particularly thank John Pourtless for suggestions and adroitly editing and making suggestions for all the chapters at an early stage. Additionally, chapters and sections were critically read by Walter Bock, David Burnham, Tom Kaye, Larry Martin, Ann Matthysse, Pavel Pevzner, David Pfennig, John Ruben, Steven Salzberg, and Zhonghe Zhou. Illustration contributions are individually acknowledged, but I would particularly like to thank Stephen Czerkas, who kindly permitted the use of many of his excellent drawings. I also owe a huge debt of gratitude to Susan Whitfield, artist-illustrator in the Department of Biology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who formatted the figures and skillfully rendered many of the illustrations. The book was enthusiastically received by editor Jean Thomson Black, expertly formatted by Joyce Ippolito, and superbly edited to completion by Laura Jones Dooley.

THEME

How the euphoria of paleontologists at having solved the century-and-a-half-old mystery of bird origins and the origin of flight was premature, generated by unfounded confidence in a rigid methodology that excludes geologic time and biological phenomena, some extravagant in nature; and how we have yet to discover the true ancestry of birds

INTRODUCTION

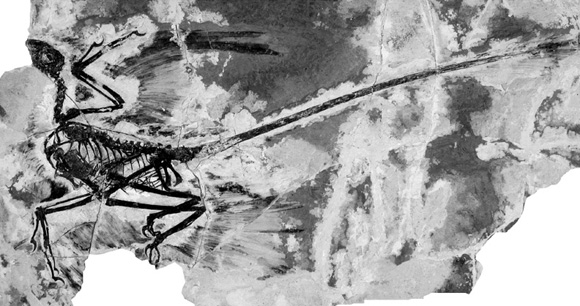

The news medias feeding frenzy on the recent dinosaur bonanzas seems never ending, with publications reporting almost weekly astounding breakthroughs on the origin of birds ranging from deciphering the color of supposed dinosaur protofeathers to unearthing birds actual ancestors. Under T. rex Discoveries, USA Today reported on 29 December 2009 that for a critter dead 65 million years, T. rex had a pretty good year as relatives turned up in study results almost weekly. Accompanying the article was an illustration of the small ancestor clothed in a pelt of presumed protofeathers. Just a year earlier, a rex-chicken nexus based on a dubious report in Science of preserved protein from the sixty-eight-million-year-old dino-icon was covered in the Associated Press: It looks like chickens deserve more respect. Scientists are fleshing out the proof that todays broiler-fryer is descended from the mighty Tyrannosaurus rexnot from a mere Allosaurus or Alioramus but from the 8-ton, mighty T. rex! Bolstered by publications in such prestigious journals as Science and Nature, the bandwagon on the direct descent of birds from earthbound feathered dinosaurs (presumably hot-blooded) has become an unchallengeable orthodoxy, such that those who oppose the consensus view find themselves unable even to offer contrary evidence or opinions, which are no longer considered respectable science. The debate is over, proclaims the paleontology editor of Nature. The sheer number of shared characters between maniraptorans (raptor theropods) and early birds is compelling, writes one book reviewer: The results have convinced all but the tiniest band of ornithologists.

Amid the haze of this hyperbolic rhetoric is an all-too-common but dangerous scientific development: the ascendency of a consensus view that has quickly evolved into a dogma. As the great twentieth-century philosopher of science Karl Popper noted presciently in 1994, There is an even greater danger: a theory, even a scientific theory, may become an intellectual fashion, a substitute for religion, an entrenched ideology.

The popular press has distorted the arguments on bird origins out of proportion. Simply put: Are birds derived from dinosaurs? Both sides agree that birds are closely allied with theropod dinosaurs; the only question is at what level. If direct descent from earthbound theropodsthe current orthodoxyis correct, then its corollarythat all avian flight adaptations and sophisticated anatomical aerodynamic architecture evolved in a context other than flightmust also be part of that doctrine. For such a theory to be true stretches biological credulity and must therefore involve an extreme in special pleading. Until the 1970s it was considered the consensus view that birds and dinosaurs shared common thecodont, or basal archosaur, ancestry. This view requires neither that flight evolved from the ground up from the worst possible anatomical plan for the origin of flight (bipedal with foreshortened forelimbs) nor a nonflight origin of aerodynamic architecture.

Much of the discussion of this dino-bird nexus is considered a direct outcome of what has come to be known as the cladistic revolution in systematic biology, a transformative methodological upheaval during the second half of the twentieth century initiated by German biologist Willi Hennig in the 1950s and stated more formally in his book Phylogenetic Systematics in 1966. Hennigs phylogenetic systematics provided the basis of a formal algorithmic system for divining the family tree of life by comparing shared, derived characters (synapomorphies), entirely skeletal in the case of dinosaurs, which are coded by the investigator and dealt with by computer algorithms that align ancestor-descendant relationships by matching taxa with increasing numbers of shared, derived characters. Largely because of its simplicity and its ability to solve, albeit in naive fashion, long-term, intractable problems of the field, cladistics soon became a dominating force, blending ideology with science. A number of scientific advancements have derived from cladistic thinking, but many scientists practicing evolutionary biology in recent decades without a pledged commitment to this phylogenetic catechism have been severely criticized, and many, including myself, have given talks at which they were the target of emotionally charged, derisive comments from audience members. In a blustering review of my book

Next page