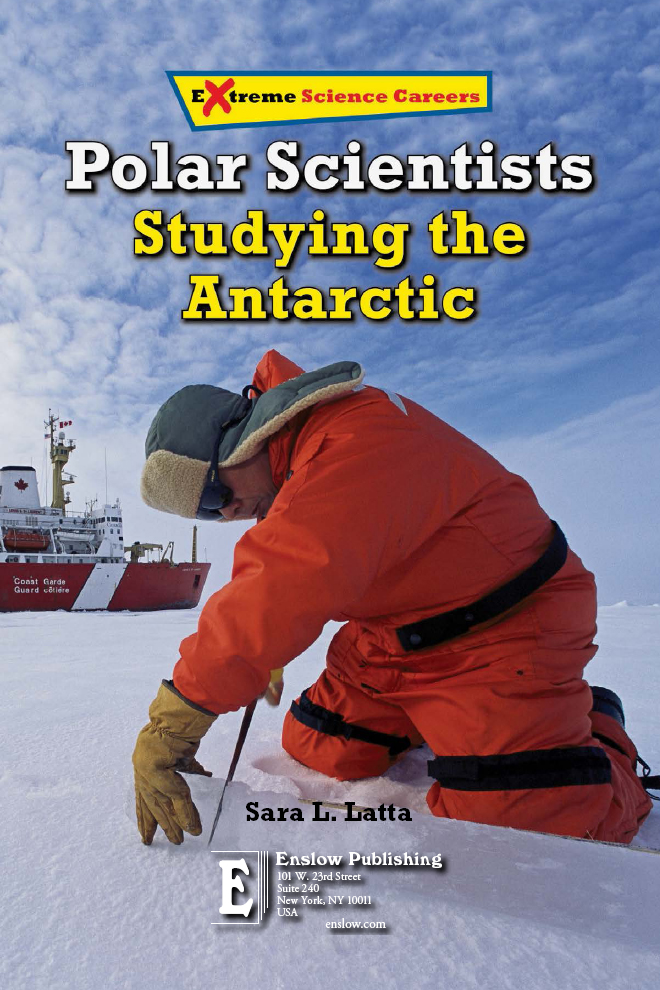

Published in 2016 by Enslow Publishing, LLC

101 W. 23rd Street, Suite 240, New York, NY 10011

Copyright 2016 by Sara L. Latta

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Latta, Sara L.

Polar scientists : studying the Antarctic / Sara L. Latta.

pages cm. (Extreme science careers)

Audience: 12-up.

Audience: Grade 7 to 8.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Discusses careers in polar science, including education, training, specialties, and salariesProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-7660-6966-4

1. ScientistsPolar regionsJuvenile literature. 2. Polar regionsResearchJuvenile literature. I. Title.

G863.L37 2015

559.89023dc23

2015011326

Printed in the United States of America

To Our Readers: We have done our best to make sure all Web site addresses in this book were active and appropriate when we went to press. However, the author and the publisher have no control over and assume no liability for the material available on those Web sites or on any Web sites they may link to. Any comments or suggestions can be sent by e-mail to .

Portions of this book originally appeared in the book Ice Scientist: Careers in the Frozen Antarctic.

Photo Credits: Andrew G. Fountain, pp..

Cover Credit: Paul Nicklen/National Geographic Creative/Getty Images (scientist taking ice sample).

Contents

This Laboratory Is Freezing!

Dinosaurs Frozen in Time

Space Rocks (on Earth)

A Big Job for Tiny Worms

Secrets of the Glaciers

The Fingerprint of the Big Bang

Athletes Under the Ice

Climate Clues to Ice Melt

Appendix: Polar Scientists: Jobs at a Glance

Chapter Notes

Glossary

Further Reading

Index

The ice of Antarctica contains clues to the history of the earths climate. Researchers use what they learn here to better understand what is in store for the future.

Chapter 1

This Laboratory Is Freezing!

S urrounding the South Pole, Antarctica is the coldest, driest, highest, and windiest place on the earth. A thick sheet of ice covers nearly all of the continent. All around this icy land are giant icebergs, pack ice, and rough ocean waves. Living and working in Antarctica can be a real challenge, even dangerous. Yet many scientists find themselves returning to this frozen continent year after year.

Imagine a day as a field scientist in Antarctica. You and your tent mate awaken from your sleep, cozy in your sleeping bags. The sunlight filters in through your bright yellow tent, bathing you and your companion in light as you melt snow to make breakfast on your cooking stove. Outside, it is 20F (29C), so you dress warmly, layer upon layer. You begin with a layer of lightweight materials that will draw any moisture away from your body. You add a middle layer of loose-fitting clothes that trap air and body warmth. Over this goes a layer of windproof and waterproof clothing that lets any moisture from your body escape. Do not forget your head and neck warmers, insulated boots, and windproof fleece gloves. Last of all, you put on the goggles that will protect your eyes from the blinding glare of the sunlight bouncing off the snow. (Out here, snow blindness is a real danger. It is extremely painful, like sunburn on your eyeballs.) You unzip the door to your tent and step outside.

The sun is shining brightly, as it has been all night long. Overhead is a clear, blue sky. Aside from the white mountains in the distance, all you can see is snow, ice, and the tents of your fellow workers. There are no birds singing, no flies buzzing, no squirrels chattering. Your world is quiet. The only sound you hear is the crunch of your boots on the snow. Welcome to life in an Antarctic field camp!

A Singular Site for Research

Scientists from around the world come to Antarctica to do research they cannot do anywhere else. Here, the largest ocean current on the planet circles the continent and the surrounding sea ice. It affects not only Antarcticas climate, but also that of the entire planet. Scientists study the atmosphere high above the continent for signs of damage to the environment. Antarcticas thick ice sheets hold clues to the history of Earths climate. Scientists compare the chemicals deposited deep in ancient ice with newer ice to help predict future climate changes.

Most scientists live in Antarctica for a few months out of the year. This is one of the buildings used as temporary housing.

The high elevation and clear, dry atmosphere make Antarctica one of the best places on Earth for astrophysicists to peer deep into outer space. Its covering of ice and snow makes Antarctica by far the best place on Earth to search for and spot meteorites, including some from the moon and Mars.

Biologists come to Antarctica to learn how living things adapt to such an extreme environment. Fossil hunters uncover clues about the life that once flourished in Antarctica. And that, as they say, is just the tip of the iceberg.

The Discovery of Antarctica

The great explorer Captain James Cook sailed around Antarctica in 1775, but bad weather and ice prevented him from discovering land. Later, he wrote that if another explorer should find the southern land he sought, I make bold to declare that the world will derive no benefit from it. Captain Cook would probably be very surprised to learn that many scientists today think of Antarctica as a very cool kind of paradise.

Cook may have thought that whatever land might lie to the south of the icy waters he sailed was of no benefit, but his descriptions of the many marine animals he saw there caught the attention of whale and seal hunters. The oil from whales and elephant seals was useful for making candles, soap, and fuel for lamps and heating. Other kinds of seals were valued for their soft, thick fur. It was not long before hunters followed in the wake of Cooks ship, killing millions of seals from the islands near Antarctica.

As the seals grew scarcer, the hunters ventured ever closer to the continent. The first recorded landing on Antarctica took place in 1821. Men from an American sealing ship landed at what is now called Hughes Bay, on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula. The captain of the ship, John Davis, correctly guessed that this new land was not another island, but a continent.

By the end of the nineteenth century, there were few fur or elephant seals left in the Southern Ocean. Commercial seal hunting was all but over. Whale hunting, though, continued well into the twentieth century. Whales are no longer plentiful in the Southern Ocean, but the seal populations have since recovered.

Some of the nineteenth-century whale and seal hunters, to their credit, were also amateur scientists. Others carried professional scientists aboard their ships to collect specimens and make observations. The scientists reports made the rest of the world hungry for more information about this icy land. While the whalers and sealers did terrible damage to the seal and whale populations around Antarctica, they also paved the way for future scientific exploration on the frozen continent.