Published in 2016 by Enslow Publishing, LLC

101 W. 23rd Street, Suite 240, New York, NY 10011

Copyright 2016 by Sara L. Latta

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Latta, Sara L.

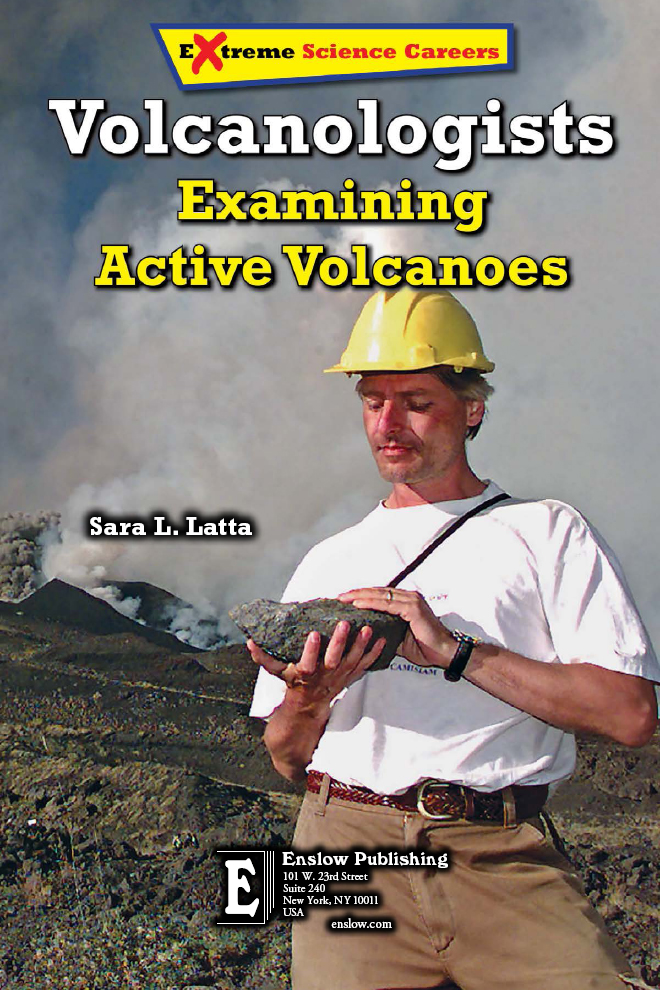

Volcanologists: examining active volcanoes / by Sara L. Latta.

p. cm. (Extreme science careers)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7660-6972-5 (library binding)

1. Volcanologists Juvenile literature. 2. Volcanological research Juvenile literature.

I. Latta, Sara L. II. Title.

QE521.3 L38 2016

551.21092d23

Printed in the United States of America

To Our Readers: We have done our best to make sure all Web site addresses in this book were active and appropriate when we went to press. However, the author and the publisher have no control over and assume no liability for the material available on those Web sites or on any Web sites they may link to. Any comments or suggestions can be sent by e-mail to .

Portions of this book originally appeared in the book Lava Scientist: Careers on the Edge of Volcanoes.

Photo Credits: .

Cover Credit: AP Images (volcanologist examining lava sample).

Contents

Volcanoes: Creators and Destroyers

Journey to the Center of the Earth

The Fury of Vesuvius

Hawaiian Hot Spots

Space Volcanoes

Into the Mouth of the Volcano

Deep Sea Volcanoes

Supervolcano!

Saving Lives When Disaster Strikes

Careers in Volcanology

Appendix: Volcanologists: Jobs at a Glance

Chapter Notes

Glossary

Further Reading

Index

Volcanologists study volcanoes like Mount Hood in order to learn more about the earths interior and to be able to better predict when eruptions might occur.

Chapter 1

VOLCANOES

Creators and Destroyers

T he Puyallup Indians of the Pacific Northwest tell the legend of an old woman named Loowit who tended the only fire in the world. People came from every direction to gather embers from that fire. She was so dedicated to her task that the Great Spirit Sahale decided to give her eternal life. But instead of being grateful, Loowit cried. She did not want to be an old woman forever. So he granted her wish to spend eternity as a beautiful young woman.

The news of her beauty spread far and wide. One day Sahales sons Klickitat and Wyeast came to see her. Both sons fell in love with Loowit, but she could not choose between them. The young men fought a mighty battle over the beautiful Loowit, burning and burying entire forests and villages. Sahale was beside himself with anger. He struck down the three lovers: Loowit, Klickitat, and Wyeast. In their places, he created enormous mountains. Loowits mountain, today known as Mount St. Helens, was a beautiful, evenly shaped cone, topped with a brilliant white headdress. Wyeasts mountain, now called Mount Hood, lifts its head in pride. And tender-hearted Klickitats mountain, now Mount Adams, bends its head in sorrow toward its beloved young maiden.

Mount St. Helens Stirs

In the spring of 1980, the beautiful Mount St. Helens began to awaken from her slumber. The often-climbed volcano in Washingtons Cascade Range had been quiet for over a century. After days of earthquakes that gradually became stronger, a volcanic explosion blasted a 250-foot-wide crater near the top of the peak.

Within the next few weeks, the rumbles continued, and the crater grew. A bulge appeared on the north side of the volcano as molten rock, or magma, rose up from deep within the earth. Scientists monitoring the volcano were very concerned. They knew that if the volcano erupted, it would put many in danger. Scientists declared a red zone in an area around the volcano. Only scientists, law enforcement, and other officials were allowed in this area. Everyone else was ordered to leave and stay outside the red zone. Journalists and tourists joined the group at the edge of the red zone. They hoped to witness the first volcanic eruption in the continental United States since 1914.

May 18, 1980, dawned bright and clear. Dave Johnston, a volcanologist working for the United States Geological Survey, was on duty at an observation post about six miles north of the volcano. Johnston was in charge of studying the gases coming from the volcano. He had studied active volcanoes in Alaska, and understood just how dangerous they could be. Still, he knew that thousands of lives would be at risk when the volcano blew. Someone had to monitor the volcano, so he chose a spot that seemed fairly safe.

The huge crater near the top of Mount St. Helens was created during its violent eruption in 1980.

At 8:32 A.M., an earthquake shook the volcano. The bulge on the side of Mount St. Helens collapsed and slid away in the largest landslide ever recorded. By radio, Johnston sent the message, Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!

Seconds later, the scientist was engulfed in the gigantic blast, which traveled 17 miles (27 kilometers) north of the volcano at speeds of up to 300 miles (480 km) per hour. The blast produced a column of ash and volcanic gas that rose more than 15 miles (24 km) into the atmosphere. Over the course of the day, the wind blew 520 million tons (470 metric tons) of ash eastward, blocking light from the sun. The city of Spokane, 250 miles (400 km) from the volcano, was plunged into darkness.

Just after noon, avalanches of hot ash, pumice, and gas poured out of the crater at 50 to 80 miles (80130 km) per hour. The hot rocks and gas melted some of the snow and ice on top of the volcano, creating a flood of water that mixed with loose rocks and dirt to form a volcanic mudflow, or lahar. The lahar poured down the volcano into river valleys, ripping trees from their roots and destroying roads and bridges. In the end, the volcano blast and its aftereffects killed fifty-seven people, including Johnston. His body was never found. Countless animals died. The surrounding lush green forest became a wasteland of mud, ash, and debris.

After the initial eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, five more explosions occurred in the following months, including this one on July 22.

The Mount St. Helens eruption, as terrible as it was, is far from historys most disastrous. The AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius, in southern Italy, killed thousands of people living in Pompeii and Herculaneum. In modern times, the 1902 eruption of Mount Pele in the West Indies completely destroyed the nearby city of St. Pierre and caused the deaths of twenty-nine thousand people.

The Volcanoes Gifts

Volcanoes are not all bad! Over the long term, volcanoes have played a key role in forming and modifying the earth. More than 80 percent of the earths surface arose from volcanic activity.

Over time, volcanic materials break down to create rich, fertile soil. This is one of the key reasons that so many people live in the shadow of volcanoes, especially in tropical areas where valuable nutrients in the soils are quickly used up. Most of the large sugar, coffee, and cotton plantations in Central and South America, Indonesia, and the Philippines are located downwind from recently active volcanoes. In many parts of the world, especially in Iceland, people harness the heat generated inside some types of volcanic systems to produce electrical energy. And for scientists, volcanoes offer a fascinating glimpse into Earths fiery interior.