Table of Contents

Guide

Before & After

Reading Activities | Level: R Word Count: 2,967 words 100th word: rock |

Before Reading:

Building Academic Vocabulary and Background Knowledge

Before reading a book, it is important to tap into what your child or students already know about the topic. This will help them develop their vocabulary, increase their reading comprehension, and make connections across the curriculum.

Look at the cover of the book. What will this book be about?

What do you already know about the topic?

Lets study the Table of Contents. What will you learn about in the books chapters?

What would you like to learn about this topic? Do you think you might learn about it from this book? Why or why not?

Use a reading journal to write about your knowledge of this topic. Record what you already know about the topic and what you hope to learn about the topic.

Read the book.

In your reading journal, record what you learned about the topic and your response to the book.

After reading the book complete the activities below.

Content Area Vocabulary

Read the list. What do these words mean?

contiguous

ecosystem

gravity

hydrothermal

infrared

lava

magma

seismic

spectrometer

submersible

tsunami

After Reading:

Comprehension and Extension Activity

After reading the book, work on the following questions with your child or students in order to check their level of reading comprehension and content mastery.

What fields should you study to become a volcanologist? (Text to self connection)

Why did the eruption of Mt. St. Helens trigger a greater need for volcano research? (Asking questions)

Why is it important to study past volcanic eruptions? (Summarize)

Explain how technology is changing volcanic research. (Asking questions)

What words did the author use to help you visualize a volcanic eruption? (Visualize)

Extension Activity

Volcanoes were a mystery for thousands of years. Cultures all around the world have legends that explain volcanic eruptions. Research volcanic legends and read how various groups explain volcanic activity. Then write your own legend to explain how volcanoes are formed or why they erupt. Share your legend with your teacher, classmates, or family.

KILLER MOUNTAIN

Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it! Those were the last words anyone heard from David Johnston. He was closely monitoring a steaming, trembling snow-capped mountain near Vancouver, Washington. Mount St. Helens had not erupted in more than 100 years. But two months earlier, an earthquake jolted it to life. Homes were evacuated and roads were closed as hundreds of explosive blasts of steam burst from the volcano. Earthquakes shook the area. Scientists knew pressure was building up inside the mountain. They could see the north side had grown outward almost 450 feet (140 meters). This was evidence that molten rock, called , had risen high into the volcano. They felt that a massive eruption could happen soon. But when?

On May 17, 1980, after two months of thousands of daily earthquakes and more steam blasts, the volcano was silent again. Many observers were there to watch the expected drama. They went home, thinking that the excitement was over.

But it wasnt.

On May 18, 1980, just seconds after David radioed those final words to his colleagues, the huge mountain blew itself apart in the worst volcanic event in the United States since 1915. His monitoring station was more than five miles (8 kilometers) away, which he considered a safe distance.

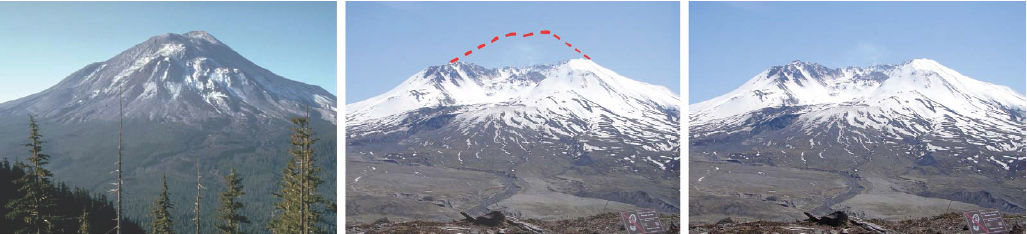

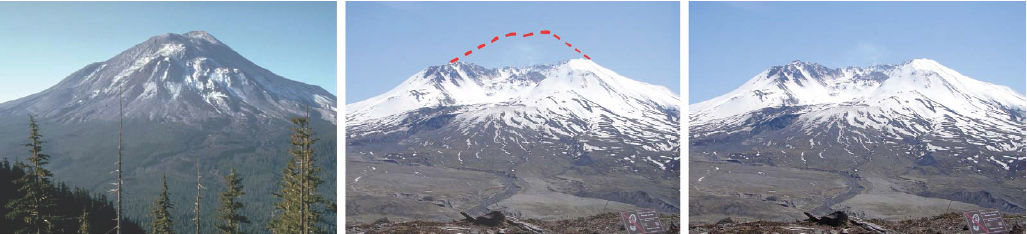

March 1980, small phreatic, or steam, explosions began.

April 1980, a bulge developed on the north side of Mount St. Helens as magma pushed up within the peak explosion.

May 1980, Mount St. Helens erupts in a massive explosion.

An aerial view of Mount St. Helens showing the Plinian eruption column on May 18, 1980.

A huge landslide bulldozed down the mountain at almost 700 miles (1,126 kilometers) per hour, crashing over everything in its path. Debris roared through the land below, as far as 14 miles (23 kilometers) west of the blast. The explosion that followed sent ash, magma, rocks and sand high into the air. David and his trailer were never found. It was assumed that both were engulfed by the blast and buried in the debris from the landslide. Fifty-six other people also were killed that day.

Immediately before the blast, an earthquake loosened the snow and soil on the north side of the volcano. Johnston was probably alerting his colleagues to the huge swell of dirt and snow that broke free and started rushing down the mountain.

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens destroyed more than 230 square miles (370 square kilometers) of forests and the wildlife that lived there.

The ground covering had kept the volcano from releasing the building pressure. Now the mountain was free to explode, and thats what it did.

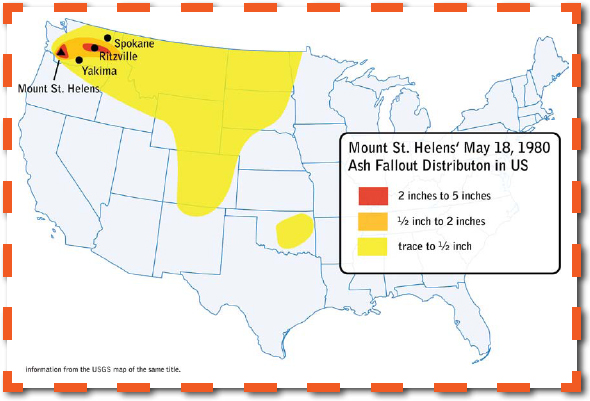

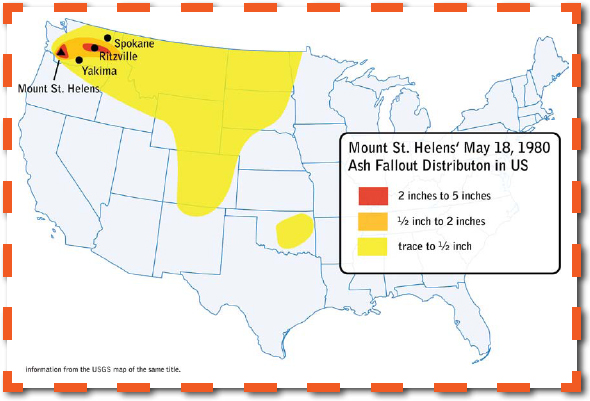

For the next nine hours, ash and magma spewed thousands of feet up in a three mile (4.8 kilometer) wide plume. People 30 miles (48 kilometers) away reported that burned pinecones and pebbles rained down around them. The day started with the largest landslide in recorded history and ended with a devastating volcanic eruption that spread ash and debris over thousands of miles of landscape. It took many years for the area to recover.

Even though the eruption of Mount St. Helens was a disastrous event, it did some good. It taught scientists an important link between earthquakes and volcanic activity. Some refer to the eruption of Mount St. Helens as the dawn of earthquake science in the United States.

Left: This photo of Mount St. Helens was taken a day before the May 1980 eruption. Middle and Right: The volcano after the eruption with a line showing what disappeared.

Map showing the distribution of ash fallout after the 1980 eruption.

Since that terrible day, scientists have learned a lot about how volcanoes grow and change, as well as how they are linked to earthquakes. Scientists like David, who lost his life monitoring Mount St. Helens, are a brave bunch. They are called volcanologists. Volcanologists may have the most dangerous job in the field of science.