Introduction

Oh hell, I wanted to talk to you, Dorothy Parker wrote. So here's this letter. Then she sat down and typed five single-spaced pages to Alexander Woollcott, five pages that make you feel as if you are sitting across a table from her, having smoke and memorable observations blown into your face. You hear her, and not just because she was such a vivid writer. You hear her because women's letters talk. They are monologues, dialogues, diatribes: They are voices fixed on paper. Like women talking over the back fence, the telephone, the breakfast plates, or the business lunch, women's letters rarely just exchange information. Instead, they tell stories; they tell secrets; they shout and scold, bitch and soothe, whisper and worry, console and advise, gossip and argue, compete and compare. And along the way, theyusually without meaning towrite history.

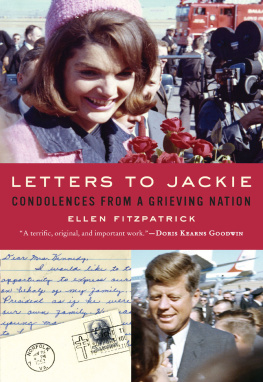

In these pages, you will hear the frontierswoman of 1852 and the feminist of 1974, the flirtatious teenager of 1777 and the runaway slave of 1862. You will hear the poet, the doctor, and the breast-cancer survivor, the devout Quaker and the president's mistress. You will hear the soldier's wife, the soldier's mother, and, even in the nineteenth century, the soldier. You will hear famous voices, like those of Abigail Adams, Jacqueline Kennedy, Amelia Earhart, and Katharine Graham. More often, you will hear voices of women whose names you never knew.

But for all the variations and intonations, you will hear something universal as well. In the course of our research, we rarely found a document that we thought had been written by a woman, only to get to the end and find that the signature was a man's. Apart from the fact that men tended to spell better and to have slightly less flowery handwriting, their letters naturally conducted more business, discussed and shaped more politics, in a public world where they were always more present and more powerful. Women's letters, by contrast, were often more casual, usually more intimate, and frequently more memorable.

Yet this is not really, or at least not only, a book about women. It is not limited to letters written to women or about women. It is really a book about America, as seen by women, which is why it is arranged chronologically rather than by theme. For most of America's history, women simply had no public forum in which to express the way they saw their own country. Letters (and diaries, but that's another book) were among their only outlets for recording what they saw of, how they felt about, and even how they helped to shape the world around them.

That world, of course, changed radically between the eve of the American Revolution, where this volume begins, and the war in Iraq, where it ends. The first letters here were written with quills, the last ones on computer laptops; the first ones were carried by horses, the last ones by ether. In 1775, American colonial women were living a largely rural existence, in constant proximity to death and disease, with God a palpable presence, invoked in nearly every letter. Where women lived, whether they were educated, what they worked at, and the number of children they bore were almost never choices they were able to make. Over timebut, as these letters suggest, by very small stagesthe world of the American woman was radically alteredmost powerfully by war, medicine, industrialization, electricity, birth control, and women's fight for equality. But luckily, through all the changes, the impulse women had to talk in writing never waned.

So what can you find in their letters? Most obviously, you can find historical events when they still sounded like the day's news. Dolley Madison told her sister about the burning of the White House. Cornelia Hancock described the Battle of Gettysburg, and a young immigrant widow wrote about the Triangle Shirtwaist fire. A day after the battle that began the American Revolution, Anne Hulton detailed what was not yet a legend:

The People in the Country (who are all furnished with Arms & have what they call Minute Companys in every Town ready to march on any alarm), had a signal it's supposed by a light from one of the Steeples in Town.

And the day after Lincoln's assassination, Julia Shepherd, who had been in the audience at Ford's Theater, wrote:

The report of a pistol is heard Is it all in the play? A man leaps from the President's box, some ten feet, on to the stage. The truth flashes upon me. Brandishing a dagger he shrieks out The South is avenged, and rushes through the scenery. No one stirs. Did you hear what be said, Julia? I believe he has killed the President.

In these letters, you will also find events that are far less famous but were no less dramatic. On the home front, women faced such adversaries as illness, poverty, hunger, drought, rattlesnakes, and terrible loneliness, all of which you will hear and see them battling in these pages. In 1776, a Massachusetts woman named Christian Barnes described her encounter with a rebel soldier who forced his way into her house:

I went in and endeavored to pacify him by every method in my power, but I found it was to no purpose. He still continued to abuse me, and said when he had eat his dinner he should want a horse and if I did not let him have one he would blow my brains out.

After the fateful journey west with the Donner Party in 1847, Virginia Reed described the ordeal to her cousin:

we had to kill littel cash the dog & eat him we ate his entrails and feet & hide & evry thing about him there was 15 in the cabon we was in and half of us had to lay a bed all the time thare was 10 starved to death then we was hadly abel to walk

And in 1855, still years before the use of anesthesia was common, Lucy Thurston had to undergo a mastectomy while fully conscious. Afterwards, she wrote to her daughter: