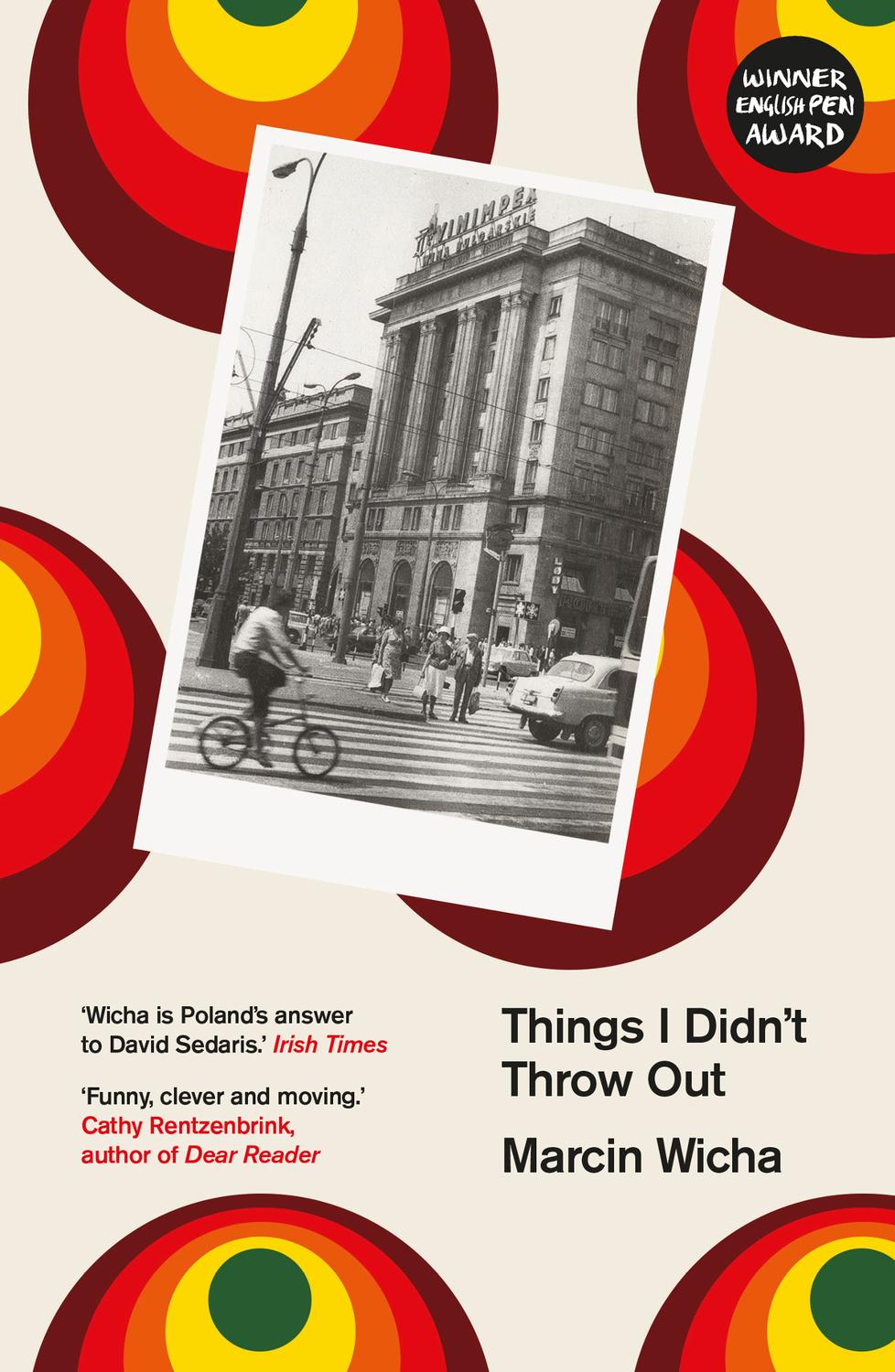

This is a story about things. And about talking. That is about words and objects. Its also a book about my mother, and so it wont be too cheerful.

I used to think that we remember people for as long as we can describe them. Now I think its the other way around: theyre with us for as long as we dont know how to pin them down with language.

Its only dead people that we can make our own, reduce to some image or a few sentences, figures in the background. Suddenly its clear they were like this or like that. Now we can sum up the whole struggle. Untangle the inconsistencies. Put in the full stop. Enter the result.

But I dont remember everything yet. As long as I cant describe them, theyre still a little bit alive.

Forty years ago and I dont understand why this particular conversation lodged itself in my memory I was complaining about some dull educational programme on Polskie Radio, and my mother said: Not everything in life can be turned into a funny story. I knew it was true. But still I tried.

She never spoke about death. Just once. A vague hand movement, a wave towards the shelves:

What are you going to do with all this?

All this meant one of those shelving systems you buy at IKEA. Metal runners, brackets, planks, paper, dust, kids drawings hung up with drawing pins. Also postcards, mementoes, wrinkled little chestnut people, bunches of last years leaves. I had to react somehow.

You remember Mariuszek from school?

A lovely boy, she said, because she remembered I didnt like him.

A few years ago, Marta and I visited his mother-in-law to bring or take something, something for kids, a playpen or what have you.

How many children does he have?

I dont know, but the mother-in-law spoke very highly of him. She said that when her roof started leaking, Mariuszek paid to have it replaced, in bituminous tile, all very expensive, and he told her: Dont you worry about money, Mummy, it will all stay in the estate.

So how is he doing?

I dont know, he works at a law firm. Dont worry about the estate. Theres still time.

But there wasnt.

My mother adored shopping. In the happiest years of her life shed set off to the shops every afternoon. Lets go into town, shed say.

She and my father liked to buy small, unnecessary things. Teapots. Penknives. Lamps. Mechanical pencils. Torches. Inflatable headrests, roomy toiletry bags, and various clever gadgets that might come in useful when travelling. This was strange, as they never went anywhere.

They would trek halfway across town in search of their favourite kind of tea, or the new Martin Amis novel.

They had their favourite bookshops. Favourite toyshops. Favourite repair shops. They struck up friendships with various always very, very nice salespeople. The antique shop lady. The penknife man. The sturgeon man. The lapsang souchong couple.

Every purchase followed the same ritual. They would notice some extraordinary specimen in the shop that sold second-hand lamps, for example, where the lamp man held court, a very pleasant citizen, to use my fathers jaunty phrase.

They would have a look. Ask about the price. Agree they couldnt afford it. They returned home. Suffered. Sighed. Shook their heads. Promised themselves that once they had some money, which should happen soon, they really must

In the days that followed they would talk about that unattainable lamp. They wondered where to put it. They reminded each other it was too expensive. The lamp lived with them. It became a part of the household.

My father talked about its remarkable features. He sketched the lamp out on a napkin (he had excellent visual memory), pointing out how original certain solutions were. He stressed that the cable had textile insulation, barely worn. He praised the Bakelite switch (I could already see him taking it apart with one of his screwdrivers).

Sometimes theyd decide to visit it again. Just to have a look. I suspect it never occurred to them to bargain. In the end, theyd make the purchase.

They were perfect customers. Kind-hearted. Genuinely interested in new merchandise. Then my father tried a sample of the green Frugo soft drink in a shopping centre and had a heart attack. We had a little time to joke about it. Even the doctor at A&E thought it was funny.

A thin trickle was all that was left after they were both gone. The TV remote. The medication box. The vomit bowl.

Things that nobody touches turn matt. They fade. The meanders of a river, swamps, mud.

Drawers full of chargers for old phones, broken pens, shop business cards. Old newspapers. A broken thermometer. A garlic press, a grater, and a whats it called? we laughed at that word, it featured in so many recipes for a time: a quirl whisk. A quirl whisk.

The objects already knew. They felt they would be moved soon, shifted out of place, handled by strangers. Theyd gather dust. Theyd smash. Crack. Break at the unfamiliar touch.

Soon nobody will remember what was bought at the Hungarian centre. Or at the Desa gallery, the folk art stall, the antique shop in times of prosperity. For a good few years, trilingual Christmas cards would arrive from businesses, always featuring a photo of some plated trinket. Eventually they stopped. Maybe the owners lost hope of further purchases. Maybe they closed down.

Nobody will remember. Nobody will say that this teacup needs to be glued back together. That the cable needs to be replaced (and where would you find one?). Graters, blenders and sieves will turn into rubbish. Theyll stay in the estate.

But the objects were getting ready for a fight. They intended to resist. My mother was getting ready for a fight.

What are you going to do with all this?

Many people ask this question. We wont disappear without a trace. And even when we do disappear, our things remain, dusty barricades.

This is supposed to be me? Well, if thats how you see me She didnt receive handmade greeting cards easily. She wasnt an easy model. In fact, with her nothing was easy.

Polish homework in Year 4: Describe your mother, or rather mum, because the school relished diminutives. God, forgive me, because I wrote: My mother has dark hair and is rather stout. Children have a different concept of weights and measures.

The Polish teacher weighed a hundred kilograms and underlined the phrase rather stout. She pressed the ballpoint pen down so strongly that she ripped through the paper. On the margin she carved the words: I wouldnt say that. My mother rarely agreed with the education system, but that pleased her.

She also had what respectable compatriots called ahem. Let me repeat: respectable. Less respectable ones had no difficulty with pronunciation.

There was something disconcerting about the ostentation of her features. She had the, ahem, look. The look of someone of, ahem, ahem, descent. What descent? Ahem. Upf.