Warm thanks are due to:

Erlend Clouston and the Nan Shepherd Estate for their support and permission to reproduce the works in this volume; the Trustees of the National Library of Scotland; the University of Aberdeens Special Collections; Dairmid Gunn for permission to quote from unpublished letters. Sources for material quoted in the Introduction are given below.

Endnotes

Robert Dunnett, Nan Shepherd: One of the Scottish Moderns , The Scotsman, July 1933.

Coley Taylor, Duttons Weekly News, 1928, MS 27443/5, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Elizabeth Kyle, Modern Women Authors, Scots Observer, June 1931.

Rachel Annand Taylor to Nan Shepherd, 30 Aug 1959, MS 3036, Special Collections, University of Aberdeen.

Sheila Hamilton, Writer of genius gave up, Evening Express (Aberdeen) 15 Dec 1976.

Nan Shepherd, Wild Geese in Glen Callater, p. 75

Agnes Mure Mackenzie to Nan Shepherd, 19 May 1926, MS 2750, Special Collections, University of Aberdeen.

Nan Shepherd, James McGregor and the Downies of Braemar, p. 68

Nan Shepherd, Marion Angus, p. 120

Nan Shepherd, Charles Murray, p. 130

Nan Shepherd, The Old Wives, p. 149

Nan Shepherd, James McGregor and the Downies of Braemar, p. 70

Nan Shepherd, The Colours of Deeside, p. 54

Nan Shepherd, Wild Geese in Glen Callater, p. 75

Nan Shepherd, Descent from the Cross, p. 21.

Neil Gunn to Nan Shepherd, 26 Jul 1943, MS 15520, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Nan Shepherd to Neil Gunn, 14 Mar 1930, Deposit 209, Box 19, Folder 7, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Nan Shepherd to Neil Gunn, 2 Apr 1931, Deposit 209, Box 19, Folder 7, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

ibid.

Nan Shepherd to Neil Gunn, 15 Sep 1931, Deposit 209, Box 19, Folder 7, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Sheila Hamilton, Writer of genius gave up, Evening Express (Aberdeen) 15 Dec 1976.

The sonnet, Without My Right, published in In the Cairngorms, was originally titled Illicit Love see Nan Shepherds manuscript, MS 27442, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Nan Shepherd, The Burning Glass, p. 90.

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain, (Edinburgh: Canongate, 2011) p. 108.

Nan Shepherd to Neil Gunn, 5 Jun 1937, Deposit 209, Box 19, Folder 7, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Nan Shepherd, Achiltibuie, p. TBA.

Nan Shepherd, Wild Geese of Glen Callater, p. 74

Nan Shepherd, On Noises in the Night, p. 143

Miss Anna Shepherd: Women Citizens, MS 27443, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Nan Shepherd, The Quarry Wood, (Edinburgh: Canongate, 1996) p. 208.

Nan Shepherd to Neil Gunn, 14 Mar 1930, Deposit 209, Box 19, Folder 7, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain ( Edinburgh: Canongate, 2011) p. 105.

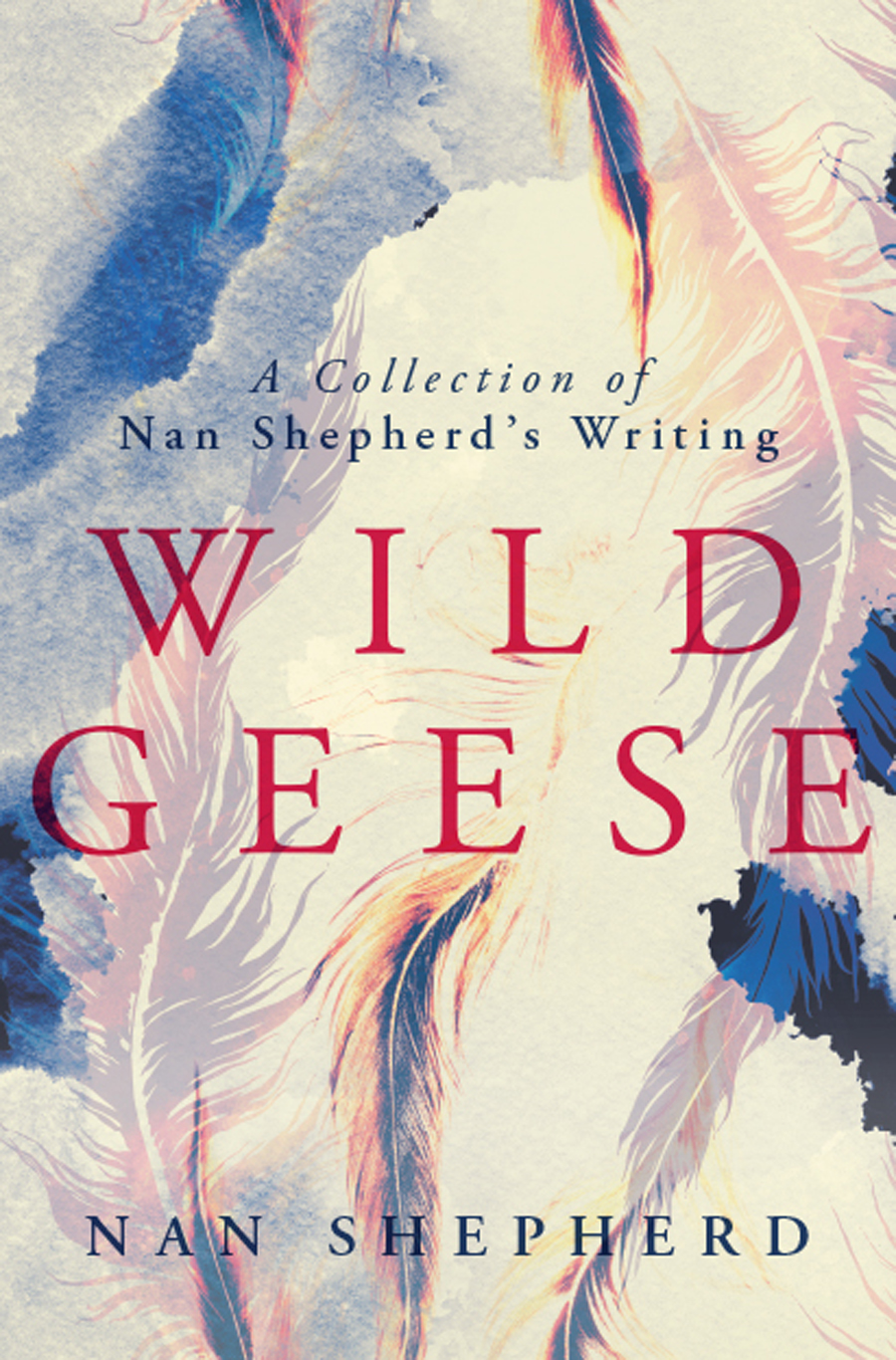

Also by Nan Shepherd

The Quarry Wood (1928)

The Weatherhouse (1930)

A Pass in the Grampians (1933)

In the Cairngorms (1934)

The Living Mountain (1977)

Galileo Publishers

16 Woodlands Road

Great Shelford

Cambridge CB22 5LW

UK

www.galileopublishing.co.uk

ISBN 978-1-903385-79-1

First published in the UK 2018

Text 2018 The Estate of Nan Shepherd

Selection and editorial work 2018 by Charlotte Peacock

Introduction 2018 Charlotte Peacock

All rights reserved.

This book is sold subject to the

condition that it shall not, by way of trade or

otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise

circulated in any form of binding or cover other

than that in which it is published and without a similar

condition including this condition being imposed

on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed in the EU

Contents

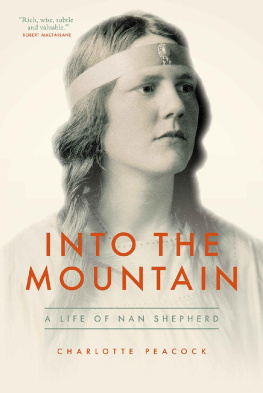

by Charlotte Peacock

I dont like writing, really. In fact, I very rarely write. No. I never do short stories and articles, Nan Shepherd confessed in 1933. I only write when I feel that theres something that simply must be written. Certainly, Shepherd was not one to shout for the sake of making noise: her oeuvre is slender. During her lifetime (1893-1981) she published just five major works.

First, between 1928 and 1933, came three complex and remarkable novels: The Quarry Wood ; The Weatherhouse ; and A Pass in the Grampians . Declared Scotlands answer to Virginia Woolf,

Readers and critics eagerly waiting for what Miss Shepherd did next, however, were disappointed. She appeared to have lost her voice. By the late 1960s her books were out of print and she had slipped into literary obscurity. Why, I wonder, did you give up literature so early?, the poet, Rachel Annand Taylor asked in 1959.

But Shepherd had not given up. Like the skein she describes in Wild Geese in Glen Callater, which, buffeted and mishandled by the wind, turned back before disappearing into diaphanous cloud, her flight was merely deflected.

Towards the end of the Second World War something else simply had to be written. An enlightened series of meditations on her beloved Cairngorms, Shepherds last book was ahead of its time. Courteously rejected in 1945, the manuscript lay in waiting for over thirty years, until she decided the world was ready for it. First published in 1977, The Living Mountain is now considered a masterpiece of landscape literature.

You can never know if your work is positively good until youve been dead a century or so, the historian and writer Agnes Mure Mackenzie told Shepherd after the publication of The Quarry Wood. It has taken less than half that time for Shepherds literary legacy to be given the recognition it deserves. The first woman writer to grace a Scottish banknote, all five of her major works are once again in print. A volume of her other writings is timely if not overdue.

During those forty-three years between books, speech did return to Shepherd, albeit intermittently. And despite what she said in 1933, it took the form of a short story and a host of articles. She also produced more verse. Gathered here is a selection of these writings, as well as some earlier pieces. For someone who professed not to like writing, each text, in whichever medium she chooses, reveals her artistry.

Her habit of engaging readers with casually conversational asides Why I should begin by writing of his drollery I hardly know is deceptive.

Her descriptions of the natural world are as vividly wrought. Scotlands blue can be azure thinned outbeaten to a transparency of itself or seems to be substance, lying like the bloom on a plum, or the pile of plush.

Light haunts Shepherds work. In Descent from the Cross, its presence is made tangible:

It was a day so filled with light that the stubble shone and in the

sun-saturated

atmosphere floated gossamers, thistledown and the seeds of

willowherb, airier

than snowflakes, more delicate than moths, as though light had

flaked itself off in filament and frond and brushed their cheeks

Written in 1942, at ten thousand words Descent from the Cross is a long, short story. Readers familiar with Shepherds novels will recognise her trademarks: her use of language English prose and dialect for dialogue; her wit; her compassion for her cast; and a female protagonist challenging convention in a small Scottish community. Like the multi-perspective, layered narratives of the novels, too, Descent from the Cross demands close reading. Then all its surfaces are seen as surfaces, its significance revealed.