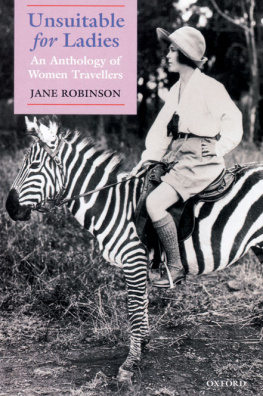

Hero stories are wearing thin. We have lived a male life, we have lived within the patriarchy. Its something else to take ownership of your own story.JANE CAMPION

THE GUARDIAN, 20 MAY 2018

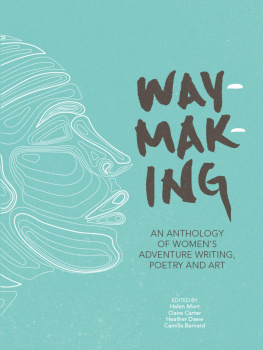

The idea for Waymaking came about during a run. For a short while Helen and I both worked in central Leeds, we met up once a week to run at lunchtime, heading from the university, through Headingleys ginnels, along hidden trails to the woods on the north-western edge of the city.

We would talk about many things as we ran, but one of the things we most keenly discussed was what a womans narrative of wild adventure would look like. And by narrative we were thinking prose, poetry, visual art; there are so many ways to express the creativity inspired by being outdoors.

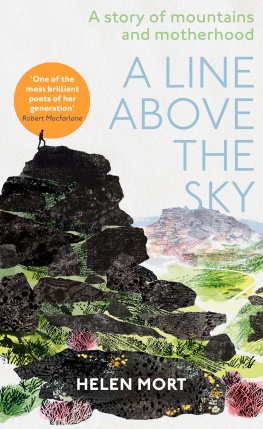

While there are accomplished female writers and artists out there and we have early pioneers like Nan Shepherd and Gwen Moffat to look to I think our voices are often not heard above the, at times, clichd stories of men conquering mountains, rock faces and other wild places.

We wanted to explore this more, and got talking with Claire, a poet and filmmaker then working at Vertebrate Publishing, who was very supportive. Waymaking was born. After speaking with Jon Barton at Vertebrate to see whether he would be interested in publishing such a book, a website was built and the call-out for contributions began in earnest. The submissions were surprising and recognisable, active and still, participatory and observational. Women were voicing and marking all sorts of narratives from the outdoor and the wild.

Roll forward a few years and here we are, with a successful Kickstarter campaign and generous support from Alpkit. This book wouldnt have happened without Vertebrate taking it on, bringing our ideas and everyones contributions to print. Camilla has been a great editor for the book; her enthusiastic, considered and honest thoughts certainly helped to shape my contribution for the better.

At the heart of Waymaking is a desire to encourage more women to express their love of the wild and adventure, and to get these voices heard. All royalties will be split equally between two charities: Rape Crisis and the John Muir Trust. Thank you to everyone who contributed and to everyone who has supported this book. We hope you like what you read and see.

Running with no steps or breaths.

Climbing with no moves.

Watching without thinking.

Sharing without judging.

Dancing without caring.

A day spent without a narrative.

No failure, no success.

Pure absorption.HAZEL FINDLAY , NO-SELF

I grew up in love with everything outdoors, and most particularly with Dartmoor, where my grandparents lived and where wed spend our holidays tramping from tor to tor, swimming in the ice-cold Dart and scrambling up and down scree. That wild, upland landscape is still the wellspring of my imagination. Everything I write is rooted in landscape and nature; yet it remains a genre dominated by men. Part of the problem is the barriers women often face in becoming a protagonist in a world removed from the domestic or the professional. Yet given half a chance and perhaps a courageous example to follow, like the women in this book we can move through the world just as freely as men.

Some years ago I gave a talk about the process of writing my second novel, a process during which I set out alone to walk north up the A5 for four days and three nights. To be clear, I didnt wild-camp: I booked B&Bs and pubs and simply walked between them, and in busy suburban England there wasnt even any possibility that I could have got lost. Yet while it pales into insignificance measured against the adventures described in this collection, this simple trip still felt like a challenge because it meant, at every stage, going against what other people believed I should do.

After the talk, a woman approached me: I could never do that, she said, shaking her head. Of course you could, if you really wanted to, I replied with an encouraging smile. Oh no, I honestly couldnt Id be way too scared. And my husband wouldnt like it, anyway.

The stories women are told and which we also tell ourselves about what is safe or acceptable or possible for us reflect neither our true capabilities or the risks the world really presents. They are stories that contain and circumscribe us and make us fearful; they deny us our full agency, our right to gamble; they keep our world small, and often domestic. The irony, of course, is that it is in the domestic that so frequently the greatest danger waits.

What does it look like when despite these narratives women go out and take up our full space in the world; when we answer a need to come into relationship with wild places in a way that is unmediated by guardians or gatekeepers; or when we push our bodies and minds to places that are impossible to find indoors? These words and images are a glimpse of that world seen through the eyes of women who may not think of themselves as pioneers may in fact shrug that label off, or point to others, anyone but themselves but who, for those of us yet unsure, or hesitant, are exactly that.

And theres something else this collection demonstrates. The female relationship with nature and landscape is often described as more spiritual, more physical and embodied, or more nurturing than the male encounter. But those seeking an essentialist view of how women relate to wild places one in which women as a group share certain experiences and preferences relating to the natural world, experiences and preferences which perhaps can be discovered by reading this book may be disappointed. The voices and perspectives in Waymaking are radical precisely for their sheer variety, something that demonstrates the profound and manifest truth that the female experience of the wild like all female experiences is simply the human one; which is, like humans, infinitely varied.

In Waymaking you will find women seeking solitude and women travelling in company; women out to conquer and women who need to commune; women who are fearless, and women battling their fear; women who are mothers, daughters, wives and lovers, and women who tell us nothing about those parts of their lives; white women, women of colour and First Nation women; women of deep faith and of none; bruised, broken and heartsore women, and women focused only on how their skill and their sinews and muscles can carry them up, over, into and away.

Climbing, running, wild swimming, skiing, mountain biking, sailing, working and walking everywhere from Cumbria to Antarctica, the Alps to Alaska, Patagonia to Wyoming and Ireland to Australia, meet the adventurers, the waymakers, the women who have found their place in the wild world: All of them, out there, in the sun/and wind, making their way/under the tremendous, as Ruth Wiggins writes.

May they inspire you to do the same.

MELISSA HARRISON

Suffolk, April 2018

Lost Valley, Glen Coe, Scotland by Tessa Lyons

Gravel road, once short

stretches hot, sore and dusty.

A stranger points: fountain.

Paella for one?

She says: walk with heart open