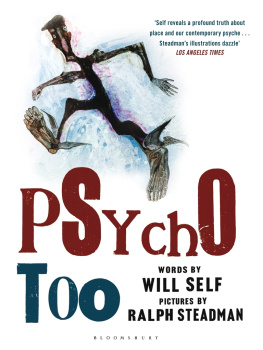

The right of Will Self to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books. You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

who kept on at me.

I N 1991 I WAS living outside Oxford and broke. I was paranoid as well, convinced that tax inspectors were surveying the isolated house we lived in from a hide, cleverly constructed to look like an enormous poll-tax demand. In order to persuade officials in the council offices to leave us alone, I went into town shoeless, dressed in a donkey jacket fastened with tow rope, and bought them off with three crushed fivers and a show of imbecility (perhaps not altogether a show).

Together with an acquaintance, Phil Robson, an able and humane psychiatrist (not quite an oxymoron) who was then running the Chilton Clinic drug dependency unit in Headington, I conceived of writing a book on drugs that would bring in some cash.

Needless to say, nothing came of this meretricious undertaking. Phil and I couldn't really agree on anything much beyond what we didn't believe in; and as for a methodology, it chopped, changed and eventually disintegrated altogether.

Drug use and procrastination often go hand in tourniquet, so there seemed a certain justice in this. But further, I had been troubled by the idea of writing a book-length work exclusively on drugs for a number of reasons. First and foremost there was my very English dread of, as De Quincey put it, 'twitching away the decent drapery' and revealing personal scars and chancres to the eyes of the world. I knew damn well that a large part of what sold the treatment of the book to its potential publisher was the expectation that I would publicly grass on myself.

This in turn led to two further problems: the ever present possibility of harassment by the police; and an allied difficulty, the fact that unlike so many people who write on the subject I was not about to beat my tits and proclaim: 'I used to be a teenage werewolf, but I'm all right naooooo!' Or, as Lou Reed so succinctly puts it: 'Does anybody need another rock-and-roll singer, whose nose he says has led him straight to God?' And by the same token, does anybody need another piece of drug pornography, aimed at giving straights a hit on the blunt - yet tapering - pipe of chemical ecstasy?

And to admit to, or attempt to put forward, even remotely serious views on the politics of the subject would be asking for more opprobrium. There's something about sumptuary militancy that doesn't quite come off: 'March Now For More Creme Brulee!' is not a slogan calculated to win many conscientious supporters.

But the fact is that the Gordian knot of hypocrisy is now tied far too tight round 'drugs' for anyone to be able to cut it, unpick it, or do anything much but gnaw frustratedly at its hempen strands. At different places in the pieces assembled here on the subject, I quote Thomas Szasz, the veteran anti-psychiatrist: 'The so-called debate on drugs has become boring.' Quite so.

But anyway, when I came to assemble the material for this volume I saw that a large part of it was concerned with the culture of drugs, and that scattered throughout the various pieces were all the arguments and points of information that I would have wished to bring together in a book.

However, the bulk of the book is not about drugs, but rather represents the fruits of being prepared to do more or less what any editor asks me to do, having calculated the ratio of glibness to money that the commission represents. For the sad fact is that all too often the pieces I have written that have required all the labour of lifting an arse cheek and pooting it out have garnered more attention - and more importantly more money - than those I worked on for long periods and took seriously. The culmination of this tendency is the state-of-English-culture piece reproduced here, which I agonised over for a full month, and which then was published to resounding silence on all fronts.

It is characteristic of collections such as this for the author to preface them with some remarks on how things have changed since they were first written. However, in this case the pieces were written over only three or four years and not much seems to have invalidated them in terms of the march of time. Excepting, I suppose, that a chronic optimist would now view all that I had to say on the conflict in Northern Ireland a year ago as an irrelevance, given the advance of the peace process. I am not a chronic optimist.

What the tight, temporal grouping does evince, though, is the preoccupation I have had with various writers and thinkers over this period. Most notably William Burroughs, J. G. Ballard, Adam Phillips and Thomas Szasz. I make no apology for this, and hope that the reader experiences the cross-referencing of ideas that these preoccupations have engendered as a more or less acceptable curdling of the whole dish.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank all of those who have published my stuffover the years. My career as a cartoonist was aided and abetted by among others: Anna Coote, Julian Rothenstein, John Fordham, Marcel Berlins, Vicky Hutchings and Cat Ledger. As a journalist I have tended to write for as many different publications as there are pieces in this volume, but there are some people I have maintained a continuing commissioning relationship with, and who have provoked some of the better writing I have done. In particular: Michael Watts, Andy Anthony, Tom Shone, Nick Lezard, Redmond O'Hanlon and Deborah Orr.

Thanks are also due to Shane Weller, Mary Tomlinson and all at Bloomsbury who helped with the preparation of the manuscript.

But I think the last word on both drugs and journalism must go to an anonymous man in Boston who I had dinner with in May of this year, who looked at me long and dolefully over the rim of his Martini, before pronouncing: 'I've given up smoking marijuana - it makes me think too much about journalism.'