Published 2002 by

Routledge

Taylor and Francis Group

270 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10016

Routledge

Taylor and Francis Group

2 Park Square

Milton Park, Abingdon

Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

Copyright 2001 by Beth LaDow

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

1 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

LaDow, Beth.

The medicine line : life and death on a North American borderland / by Beth LaDow.

p. cm.

Includes bibliograhical references a(p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-415-92765-X

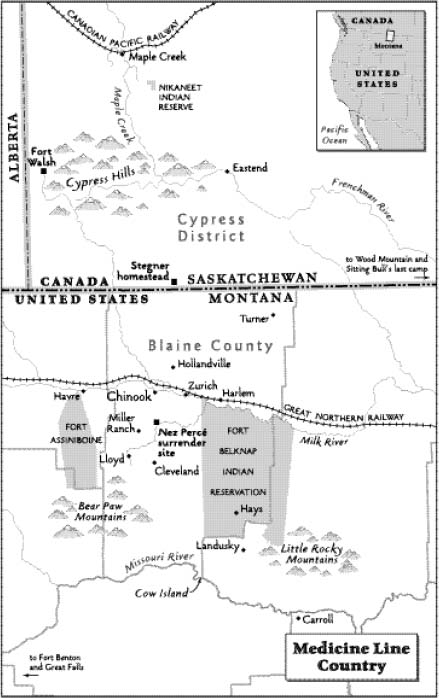

1. Blain County (Mont.)History19th century. 2. Cypress Hills (Alta. and Sask.)History19thcentury. 3. For Belknap Indian Reservation (Mont.)History19th century. 4. Frontier and pioneer life MontanaBlaine County. 5. Frontier and pioneer lifeCypress Hills (Alta. and Sask.) 6. Norther boundary of the United StatesHistory19th century. 7. Indians of North AmericaMontanaBlaine County History19th century. 8. Indians of North AmericaCypress Hills (Alta. and Sask.)History19th century. 9. PioneersMontanaBlaine CountyHistory19th century. 10. PioneersCypress Hills (Alta. and Sask.)History19th century. I. Title.

F737.B63 L34 2001

978.61502dc21

00-042496

T o those whose generosity, knowledge, help, and encouragement made this parcel of vain strivings into a book, all of whom I cannot possibly name, my deepest gratitude: Dave Walter and the staff at the Montana Historical Society; Donny White and the Medicine Hat Museum and Archive; Malinda Drury and others at the Southwest Saskatchewan Old Timers' Museum; Jude Sheppard at the Blaine County Museum and Blaine County Library; Preston Stiff Arm and the Fort Belknap Tribal Archives, Fort Belknap College; Don Richan and the Saskatchewan Archives Board in Regina; and the staffs of the James J. Hill Reference Library, Eastend Museum, Manitoba Provincial Archives, Brandeis University and Harvard University libraries, University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections, Glenbow Museum, American Museum of Natural History, Public Archives of Canada, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, and Denver Public Library. Also, Robert Utley, Gerald Davidson, Michael Doxtater, Bill Asikinack, and others on-line on H-West and H-Amindian; John Bennett; Mary Stegner and JoAnn Rogers; Joyce King, Scott Armstrong, and Jennifer Long at Sherin and Lodgen in Boston; Lee Harrison and Irene Ford Grande in Helena; Michael Ober and Flathead Valley Community College; Waldine Miller Lindquist; George VandeVen, Anne Schroeder, Linda Haugen, Alice O'Hanlon, Olive Sattleen, and others in Chinook, including Richard Ford and his grouse; my students at Brandeis and Harvard Universities; participants in the University of Kansas Hall Center nature and culture colloquium, and the Western History Association and American Studies Association conferences at which I presented papers; and the Western History Association committee who gave this project the Rundell Award. I thank Ivan Doig for his early encouragement; Janet LaDow Payne and Christopher Payne for research and support; Neil Leifer, for advice on Indian law; the late John Conway, for teaching me about Canada; John Mack Faragher, for commenting on an early paper from which this project grew and William Lang and Montana, the Magazine of Western History for publishing it; David LaDow, for teaching me that writing is a craft; my extraordinary collection of neighbors in Winchester, Massachusetts, who understand community; and Andrew Caffrey and Lindsay Miller at WBUR, Boston, for discovering my radio voice.

I am especially indebted to Micha Grudin and Christine Heyrman, for inspiring me early on; Patricia Limerick for teaching me about the West and quoting from Lewis Carroll once in an airport, we shall all be queens together; Morton Keller, who reminded me during years of patient teaching just how far from the East the West really is; Peter Mancall, ace scholar, publishing advisor, and uplifting friend; the late Randy Swartz, kindred spirit and co-deviser of the diversity index, and the late Mark Alpertheir spirits endure; Sarah Flynn, wise counselor and superb editor who never let me give up; and Deirdre Mullane, Publishing Director and editor at Routledge who understood this hybrid book better than I, and the Routledge staff for their outstanding work.

Finally, for striking me with the lightning of their intelligence and spirit, I thank the late Wallace Stegner, who dwelled in and reimagined this borderland; Donald Worster, best of all possible mentors and Kansans whose brilliant and lyrical understanding of nature, ideas, and people changed my life; my parents, Jess and Jean LaDow, whose joke write that down, Flavus I may have finally taken too far; my daughter Kate, twice my companion to the borderland who grew up with this book, lovelier than it by far; my son Sam, who increasingly seems to know more history than I do; and my husband Josh Alper, editor, supporter, and life companion nonpareil with whom I'll cross the border.

THROUGH THE

LOOKING GLASS

W e do not know precisely when Sitting Bull abandoned hope, but he had certainly given up by July 12, 1881, and perhaps on that very day. In the dust of trader Jean-Louis Lgar's thirty-seven wagons and screeching Red River carts, he rode his pony through the fly-thick Canadian prairie heat, south across the Canada-Montana border, preparing to submit to the United States Army he and his Sioux followers had eluded in 1877, evading capture after their victory at the Battle of the Little Big Horn the year before. In eight days he would become the last Northern Plains Indian to surrender his rifle to a United States soldier. The surrender, like most moments of defeat, was a physical and mental journey

Sitting Bull had been resisting surrender for years. Even though he had thought about giving up at least since November 1880, he had stayed the impulse repeatedly during the spring and early summer of 1881. Rain-in-the-Face, another Sioux leader, had surrendered the summer before, followed by Gall, who took 110 households from Sitting Bull's camp along with him, and then Crow King and others. Hundreds of Sioux were abandoning the uneasy refuge of Canada for the dull security of Standing Rock Agency, a reservation in Dakota Territory maintained courtesy of the U.S. government, one of several outposts on the Missouri River. Sitting Bull was the last holdoutthe most stubborn, the most committed to his land and former way of life. By spring his remaining bedraggled band of followers was starving. Their clothes were rags, some of them rotting off their bodies. The Canadian Mounties were less openly hostile than American soldiers, but during the Sioux's four-year stay in the land of the White Mother it had become clear that food and aid were not amenities the refugees could count on. Cadging supplies from Mounties and traders, they wandered the rapidly diminished buffalo grounds between Eastend and Wood Mountainfrom a Mounted Police post near the international border to a timbered trough in the prairie thirty-five miles east of Wood Mountain called Willow