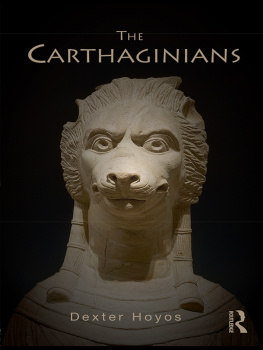

IT WAS WELL FOR THE development and civilization of the ancient world that the Hebrew fugitives from Egypt were not able to drive at once from the whole coast of Syria its old inhabitants; for the accursed race of the Canaanites whom, for their licentious worship and cruel rites, they were bidden to extirpate from Palestine itself, were no other than those enterprising mariners and those dauntless colonists who, sallying from their narrow roadsteads, committed their fragile barks to the mercy of unknown seas, and, under their Greek name of Phoenicians, explored island and promontory, creek and bay, from the coast of Malabar even to the lagunes of the Baltic. From Tyre and Sidon issued those busy merchants who carried, with their wares, to distant shores the rudiments of science and of many practical arts which they had obtained from the far East, and which, probably, they but half understood themselves. It was they who, at a period antecedent to all contemporary historical records, introduced written characters, the foundation of all high intellectual development, into that country which was destined to carry intellectual and artistic culture to the highest point which humanity has yet reached. It was they who learned to steer their ships by the sure help of the Polar Star, while the Greeks still depended on the Great Bear; it was they who rounded the Cape of Storms, and earned the best right to call it the Cape of Good Hope, 2,000 years before Vasco de Gama. Their ships returned to their native shores bringing with them sandal wood from Malabar, spices from Arabia, fine linen from Egypt, ostrich plumes from the Sahara. Cyprus gave them its copper, Elba Its iron, the coast of the Black Sea its manufactured steel. Silver they brought from Spain, gold from the Niger, tin from the Scilly Isles, and amber from the Baltic. Where they sailed, there they planted factories which opened a caravan trade with the interior of vast continents hitherto regarded as inaccessible, and which became inaccessible for centuries again when the Phoenicians disappeared from history. They were as famous for their artistic skill as for their enterprize and energy. Did the greatest of the Jewish kings desire to adorn the Temple which he had erected to the Most High in the manner least unworthy of Him? A Phoenician king must supply him with the well-hewn cedars of his stately Lebanon, and the cunning hand of a Phoenician artisan must shape the pillars and the lavers, the oxen and the lions of brass, which decorated the shrine. Did the King of Persia himself, in the intoxication of his pride, command miracles to be performed, boisterous straits to be bridged, or a peninsula to become an island? It was Phoenician architects who lashed together the boats that were to connect Asia with Europe, and it was Phoenician workmen who knew best how to economize their toil in digging the canal that was to transport the fleet of Xerxes through dry land, and save it from the winds and waves of Mount Athos. The merchants of Tyre were, in truth, the princes, and her traffickers the honourable men, of the earth. Wherever a ship could penetrate, a factory be planted, a trade developed or created, there we find these ubiquitous, these irrepressible Phoenicians.

We know well what the tiny territory of Palestine has done for the religion of the world, and what the tiny Greece has done for its intellect and its art; but we are apt to forget that what the Phoenicians did for the development and intercommunication of the world was achieved by a state confined within narrower boundaries still. In the days of their greatest prosperity, when their ships were to be found on every known and on many unknown seas, the Phoenicians proper of the Syrian coast remained content with a narrow strip of fertile territory, squeezed in between the mountains and the sea, of the length of some thirty miles and of the average breadth of only a single mile! And if the existence of a few settlements beyond these limits entitles us to extend the name of Phoenicia to some 120 miles of coast, with a plain behind it which sometimes broadened out into a sweep of a dozen miles, was it not sound policy, even in a community so enlarged, to keep for themselves the gold they had so hardly won, rather than lavish it on foreign mercenaries in the hope of extending their sway inland, or in the vain attempt to resist by force of arms the mighty monarchs of Egypt, of Assyria, or of Babylon? Their strength was to sit still, to acknowledge the titular supremacy of anyone who chose to claim it, and then, when the time came, to buy the intruder off.

The land-locked sea, the eastern extremity of which washes the shores of Phoenicia proper, connecting as it does three continents, and abounding in deep gulfs, in fine harbours, and in fertile islands, seems to have been intended by Nature for the early development of commerce and colonization. By robbing the ocean of half its mystery and of more than half its terrors, it allured the timid mariner, even as the eagle does its young, from headland on to headland, or from islet to islet, till it became the highway of the nations of the ancient world; and the products of each of the countries whose shores it laves became the common property of all.

But in this general race of enterprize and commerce among the nations which bordered on the Mediterranean, it is to the Phoenicians that unquestionably belongs the foremost place. In the dimmest dawn of history, many centuries before the Greeks had set foot in Asia Minor or in Italy, before even they had settled down in secure possession of their own territories, we hear of Phoenician settlements in Asia Minor and in Greece itself, in Africa, in Macedon, and in Spain. There is hardly an island in the Mediterranean which has not preserved some traces of these early visitors: Cyprus, Rhodes, and Crete in the Levant; Malta, Sicily, and the Balearic Isles in the middle passage; Sardinia and Corsica in the Tyrrhenian Sea; the Cyclades, as Thucydides tells us, in the mid-gean; and even Samothrace and Thasos at its northern extremity, where Herodotus, to use his own forcible expression, himself saw a whole mountain turned upside down by their mining energy: all have either yielded Phoenician coins and inscriptions, have retained Phoenician proper names and legends, or possess mines, long, perhaps, disused, but which were worked as none but Phoenicians ever worked them.

And among the Phoenician factories which dotted the whole southern shore of the Mediterranean, from the east end of the greater Syrtis even to the Pillars of Hercules, there was one which, from a concurrence of circumstances, was destined rapidly to outstrip all the others, to make herself their acknowledged head, to become the Queen of the Mediterranean, and, in some sense, of the Ocean beyond, and, for a space of over a hundred years, to maintain a deadly and not an unequal contest with the future mistress of the world. The history of that great drama, its antecedents, and its consequences, forms the subject of this volume.