The Wars of the Roses

The Author

Anthony Goodman read Modern History at Magdalen College, Oxford and is Reader in History at the University of Edinburgh. He is author of The Loyal Conspiracy: The Lords Appellant under Richard II (Routledge, 1971); History of England from Edward II to James I (Longman, 1977); co-author with Michael Cyprien, A Travellers Guide to Medieval Britain (Routledge, 1986) and The New Monarchy in England, 14711534 (Blackwell, 1988); co-editor with Angus MacKay, The Spread of the Renaissance. Essays in Honour of Denys Hay (Longman, 1990).

To the memory of my mother

First published in 1981

by Routledge & Kegan Paul

Published in 1990, 1991, 2002

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

First issued in hardback 2016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor and Francis Group, an informa business

Anthony Goodman 1981

British Library in Cataloguing Publication Data

Goodman, Anthony

The Wars of the Roses

I. Great BritainHistoryWars of the Roses, 1455-1485

I. Title

942.04 DA250

ISBN 13: 978-1-1381-4851-2 (hbk)

ISBN 13:978-0-415-05264-1 (pbk)

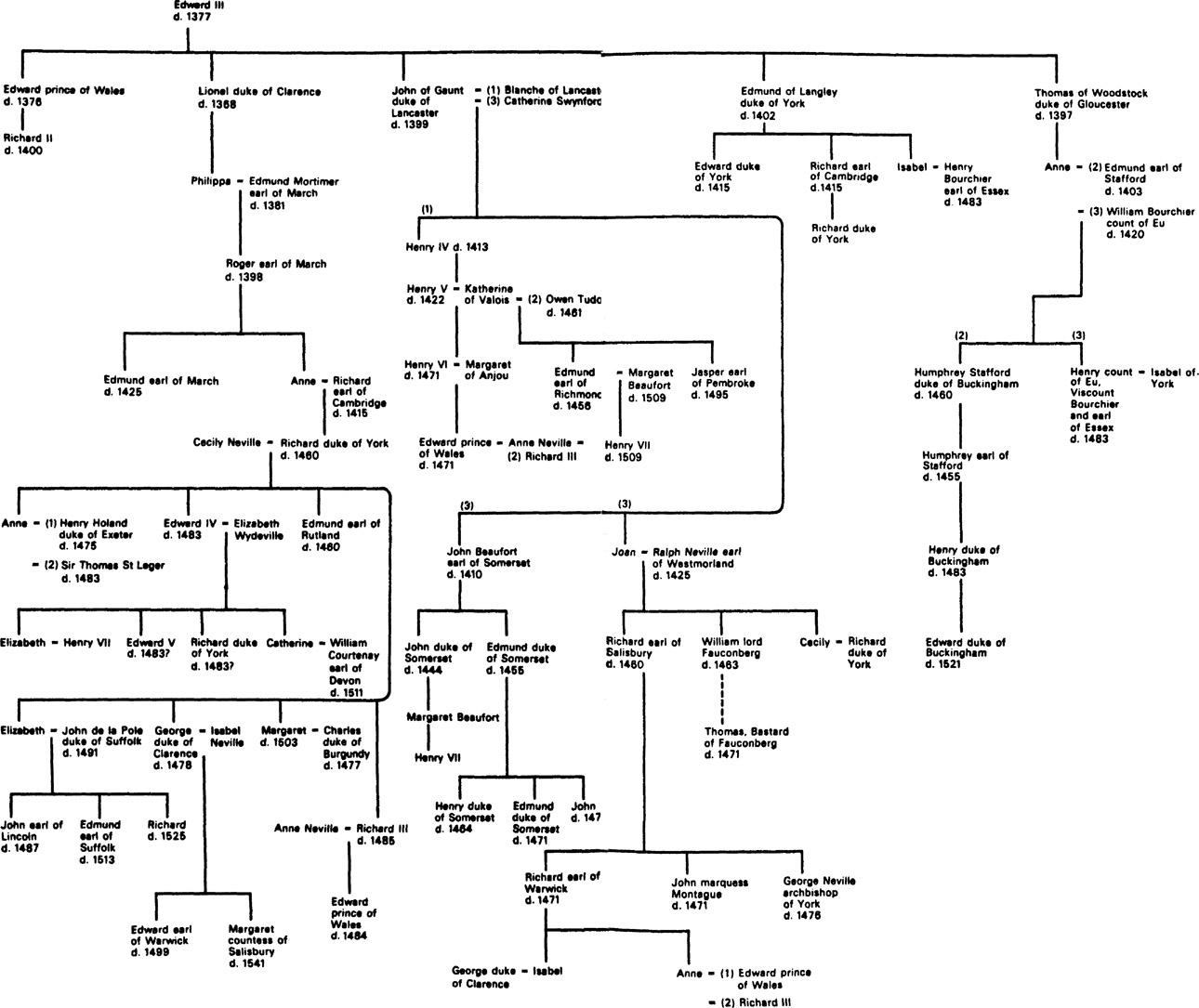

The succession to the English throne in the later fifteenth century

Since the publication of this book, the spate of works published on English politics and society in the second half of the fifteenth century, which was then in full flow, has continued unabated. The Wars of the Roses have in themselves continued to be treated as an important subject, a particular phenomenon whose study has a crucial bearing on the understanding of late medieval/early modem politics and society in England and Wales. There have been monographs on individual campaigns and battles the anniversary of Bosworth in 1985 inspired a good deal of re-appraisal. I have made additions to the Select Bibliography which reflect these scholarly trends. Here I wish to mention only three of the books I have listed, none of them specifically about the Wars of the Roses or even about England and Wales, but which collectively throw a flood of light on European warfare in the period and on its effects on society the magisterial general studies by Professor Contamine and Sir John Hale, and Dr Vales illuminating study of the techniques of warfare and the meanings of chivalry in the period.

There are two points which I wish to make about the general interpretation offered in this volume an interpretation which has the aim of stimulating consideration of the effects the Wars of the Roses had on society. The first is that I have characterized them as a series of upheavals because I have looked at them from military and social viewpoints. Concentration on political causation produces a different sort of profile, in which particular campaigns, sometimes spread over a period of years, appear as episodes in ongoing political dramas with distinctive characters and causes. From the political viewpoint, for instance, the rebellions of 14837 can arguably be accounted as one war fought over issues which were separate and in many ways different from the war which started with the campaigns of the 1450s, whose issues were finally settled in 1471.

My second point is that the list of campaigns in the Appendix is incomplete and that, therefore, as Dr Pollard has pointed out, the total I arrive at for campaigning periods can be accounted a serious underestimate. The ommissions were deliberate; I was concerned not to overstate the case I was making. Therefore, I excluded the campaign of 1452 and those after 1485, since my view that the Wars of the Roses were not confined to the period 145585 could be considered an idiosyncratic one. I also excluded within that period campaigns which I felt did not involve some widespread form of English national involvement over a sustained period and over large and diverse areas. My approach does, indeed, reflect too centralist a view of history. Those suffering in the siege of Calais in 14601 or the fighting in Northumberland in 1464 would hardly have been consoled by the assurance that the historian might write these affairs down as little local difficulties.

I owe especial thanks to Professor Kenneth Fowler for his comments on , and to Dr Angus MacKay for introducing me to Mosn Diego de Valeras and Andres Bemaldezs lively reactions to the turbulent and ferocious English. I hope that my incidental remarks about institutions and society adequately reflect the stimulating teaching of my former colleagues Professor Ted Cowan and Professor Alan Harding, with whom I taught a senior course on such aspects of late medieval British society for several years. I am grateful to the officers of county record offices who have helpfully answered my inquiries about urban financial accounts particularly to Jennifer Hofmann, Senior Assistant Archivist at the Dorset County Record Office, who brought the Bridport Muster Roll to my attention. Anna P. Campbell typed the manuscript with her customary skill.

But, above all, I owe thanks to the encouragement of my wife, Jacqueline, and to the patience of my daughter, Emma. Regrettably, my mother, Ethel Lilly Eels, did not live to see this book, to whose completion she looked forward eagerly.

The Wars of the Roses is the name commonly given by modern historians to campaigns in the second half of the fifteenth century which were fought mainly in England and Wales, but also spilled over on to Irish, French and Scottish soil, and had important international repercussions and involvements. Their starting-point has usually been taken to be the brief revolt in May 1455 headed by the richest secular magnate in the realm, Richard duke of York, a great lord in that part of Wales known as the Marches as well as in northern England. York was protesting against the enmity shown to him by those favoured by Henry VI, notably Edmund Beaufort, duke of Somerset.

Henrys grandfather, Henry of Bolingbroke, duke of Lancaster, had gained the throne in 1399 as Henry IV, by procuring the deposition of Richard II. The claim to the succession of Yorks uncle Edmund Mortimer, earl of March (whose heir York was), was passed over then. In 1459 and 1460 York again headed rebellions against counters and councillors whose hostility towards him was strongly sustained by the forceful queen, Margaret of Anjou. The wars began as a lengthy political, and eventually armed, struggle, predominantly for influence at court and in the localities, between alliances of magnates and gentlefolk. But after the success of the 1460 revolt York gave primacy to the dynastic issue. He laid claim to the throne in right of his Mortimer descent before parliament, which recognized that he should succeed Henry, displacing as heir the laners son, the young Edward prince of Wales. Soon afterwards, however, York died fighting against the queens and princes supporters who opposed the parliamentary compromise.

In March 1461 Yorks eldest son, the earl of March, was acclaimed in London by his supporters as Edward IV. Though the young king speedily drove Henry and Margaret from the realm, it was not until 1464 that the last serious Lancastrian stir was defeated. Thereafter the queen and her son maintained a threadbare court over the water, a centre for intrigue, and Henrys standard was still on occasion defiantly raised in Wales.