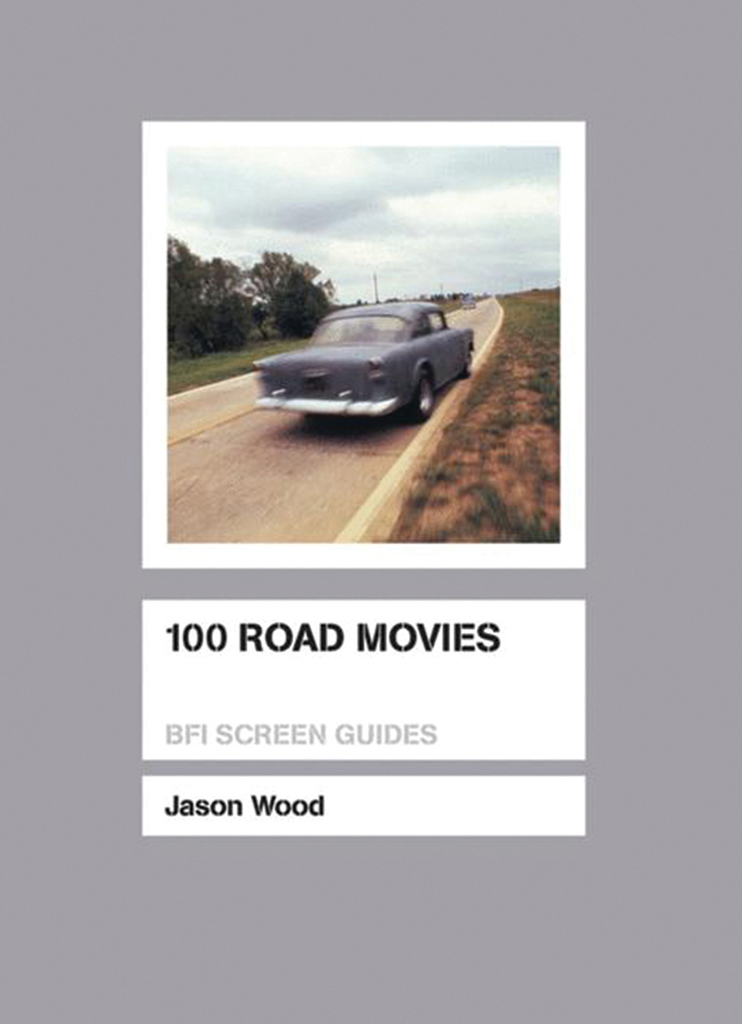

100 Road Movies

First published in 2007 by the

British Film Institute

21 Stephen Street, London W1T 1LN

The British Film Institutes purpose is to champion moving image culture in all its richness and diversity across the UK, for the benefit of as wide an audience as possible, and to create and encourage debate.

This publication Jason Wood 2007

Series cover design: Paul Wright

Cover image: Two-Lane Blacktop (Monte Hellman, 1971,

Universal Pictures/Michael S. Laughlin Enterprises)

Series design: Ketchup/couch

Set by Fakenham Photosetting Limited, Fakenham, Norfolk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781844571604 (pbk)

ISBN 9781844571598 (hbk)

ISBN 9781838714062 (ePDF)

ISBN 9781838714055 (eISBN)

Contents

by Chris Petit

I would first and foremost like to thank Rebecca Barden for commissioning 100 Road Movies and for not losing patience with me as various deadlines invariably came and went. My gratitude is also extended to Tom Cabot, Sophia Contento, Claire Milburn and Sarah Watt at BFI Publishing.

Sincere thanks also to: Geoff Andrew, Nicky Beaumont, City Screen (Deborah Allison, Clare Binns, Jo Blair, Daniel Graham, Tony Jones, Damian Spandley), Gareth Evans, Steve Jenkins, Michael Leake, Andy Leyshon, Verena von Stackelberg, Gavin Whitfield, Mark Williams, Felix Wood and Rudy Wood.

Chris Petit deserves my deepest appreciation for agreeing to write the preface.

Finally, I dedicate this book to Richard Beaumont, who is very fond of cars and of driving them.

Back in the 1970s, I drove a lot and liked driving. I thought the portable radio cassette one of the great twentieth-century inventions and whoever thought to put a radio in a car was a genius. Music and speed, combined with the ratio of the windscreen, made for an experience that was often more cinematic than the films I had to review for Time Out. Driving with the radio on transcended the dreary reality of Britain, hinted at possibilities of a mythic landscape denied by the realism of the English cinema. I saw nothing on the English screen that corresponded to a modern life that for me combined drift and boredom, jukeboxes, Alphaville, J. G. Ballard and Kraftwerk. I saw no reason why contemporary England could not be a cinematic landscape or why you could not show it through the road.

England made me restless, which is why I liked US cinema with its recurring themes of migration, pioneering and journey. I was never bored by an American road movie as long as it kept moving. Driving, like viewing film, is a suspended state and any drive well, perhaps not those to the supermarket has its own narrative: what is being driven away from (the past) and driven towards; a simultaneous journey of flight and progression. I summed up my feelings about the road in a film, Negative Space, a profile essay on the great American movie critic Manny Farber:

America. Sheer physical space. No irony, no metaphor. Distance no object. Itinerary instead of narrative. Movement, space and light rather than words on a page. Eight dollars of gas to cross three states, driving insane distances for the hell of it. After the cramped spaces of Europe, emotional and physical, America feels wide open and literal. The road becomes a movie becomes the memory of other movies, the physical space of the country reflected in its movie stars, who always knew how to move.

But there was little that could be applied to trying to make films in England from watching Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. Another part of me appreciated the austere aesthetic of European directors Bresson, Straub and Huillet, who taught me to prefer watching people by themselves to dialogue scenes, and how aloneness, as much as loneliness, lies at the heart of cinema (and the road). Godard used the road to doodle (Pierrot le fou) but it wasnt until seeing Rossellini and Wenders that I began to appreciate how making films might be possible. If directing is about correct shot selection and knowing where to put the camera, then I wouldnt change a frame of Voyage to Italy.

Lured into Wenders early film The Goalkeepers Fear of the Penalty Kick by its title and not knowing what to expect, I was intrigued by the way it squandered its plot goalkeeper loses game, hangs around, strangles cinema cashier and takes to the road in favour of heightened lesser moments: a bright yellow cigarette machine at a bus station or listening to a familiar song on a crappy transistor with variable reception. Wenders did none of the expected things, preferring the extended journey, which he followed up in subsequent German films, Alice in the Cities, Kings of the Road and Wrong Movement, voyages of discovery through landscapes suffering cultural amnesia and a country refusing to face up to its past. Where his contemporary Werner Herzog dealt with the same issues by making arduous treks through remote and hostile terrain, Wenders revealed the strangeness of the everyday the forlorn beauty of lay-bys, fast-food stands and the sort of downbeat poetry that usually passes us by.

It was Wenders who gave me my break. Radio On was partly produced by his company Road Movies (what else?). I wasnt given any audition beyond being asked how I would shoot it. 35mm black and white, I said. Looking back, Im amazed. I hadnt a clue really.

Main reasons for a film-maker (or anyone) to go on the road: fresh horizons; to save a failing relationship; to look back. Road movies are cinematic because they are not a substitute for something else. They are not filmed theatre, like a lot of movies. Despite the limited angles of filming in a car, I am thrilled by a camera inside any vehicle the way I am not when it is in a room. I was never much interested in the filmed story anyway: the-what-happens-when. Film was about space or moments or visual geometry. Godard summed it up best:

The important thing is to be aware that one exists. For three-quarters of the time during the day one forgets this truth, which surges up again as you look at houses or a red light, and you have the sensation of existing in that moment.

The road movie is a subgenre rather than one in its own right (often an afterthought of the US Western) but, returning to that idea of the subjective windscreen, among the most memorable shots in cinema are those POV driving shots in Vertigo (not a road movie as such but the most driven of films). Also there is the romantic aspect of a man and a woman in a car (as opposed to the worlds most depressing sight: four men in a car), or a man alone in a car looking for a woman (Vertigo again). For practical reasons, a road movies ideal unit is two. Two in a car is easier to shoot than three or four. Couples then went along for the ride, with the men giving directions: Rossellini and Bergman; Eastwood and Sondra Locke; Godard and Karina; Fellini and Masina. Going on the road failed to revive Rossellini and Godards marriages; Locke did not last long either.

The road flatters bad directors and brings out the best in good ones. Peckinpah, by association, is a recurring name. Rudy Wurlitzer wrote Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid for him, a kind of pre-road movie. Wurlitzer codirected Candy Mountain with Robert Frank, the great photographer chronicler of the American road and a major influence on Wenders and Jim Jarmusch. Wurlitzer wrote Two-Lane Blacktop, the last word on the American road: strung out, existential, narcotic. Three out of a main cast of four died prematurely, Warren Oates while washing his car. Its director Monte Hellman barely worked subsequently. The fate of