Perditus Liber Presents

the rare

OCLC: 1060810

book:

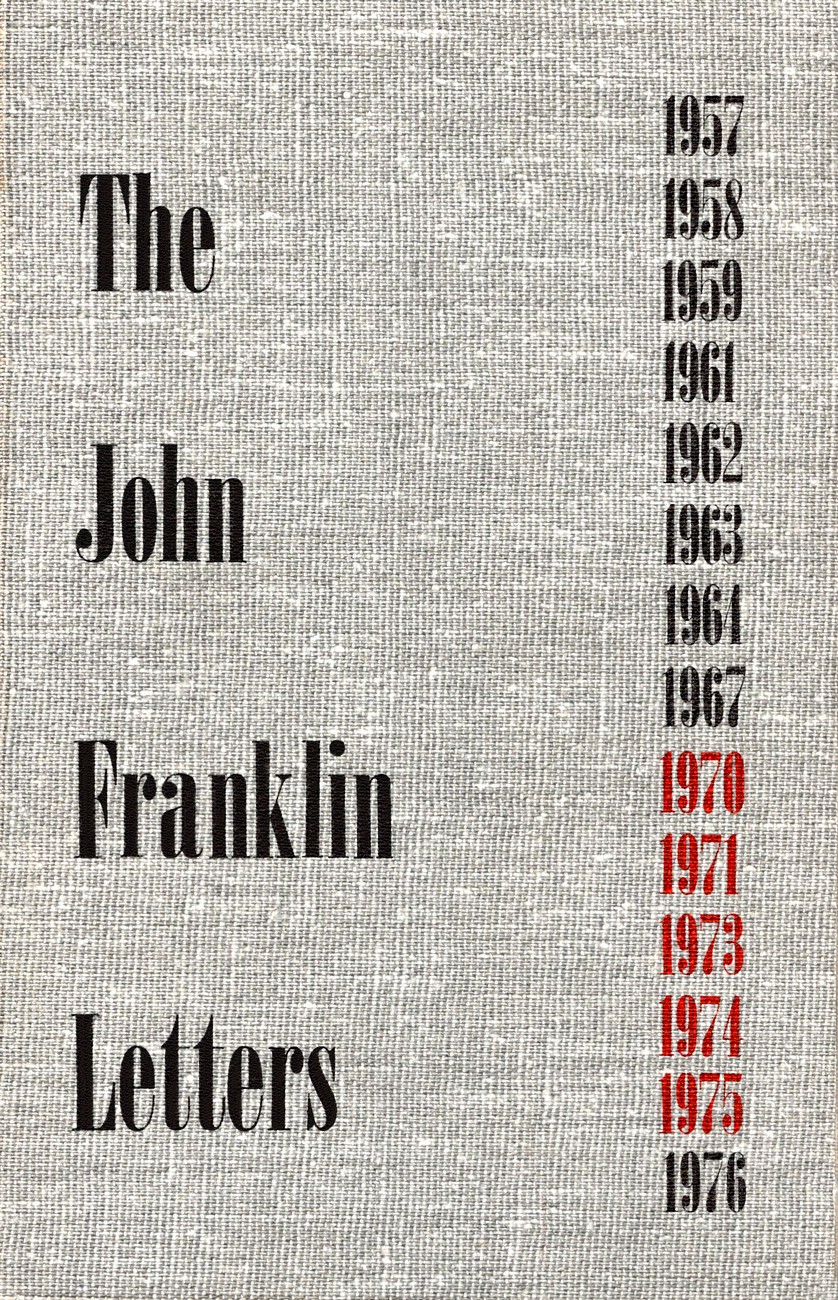

The John Franklin Letters

By

Lyle Munson

Published 1959

THE JOHN FRANKLIN LETTERS

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Ours is a nation enfeebled by political maternalism. Our voters have been conditioned to vote themselves largess out of the public treasury to rely upon government to provide them jobs, security, ease.

But government cannot give of itself; what government gives to oneeither an individual or a pressure groupit must take from others. And the public treasury is guarded only by the public conscience.

If the public conscience tolerates taking from some, to give to others, grasping men will exploit the frailty. Our politicians have done so.

Both parties in Washington are distinguished by men who seek to give their constituency what that constituency wants: tax money, which has been taken from someone elses pocket.

A public which makes such demands upon its officials precludes responsible men holding public office. That those in Washington can compromise with Atheistic Communism is not surprising. To oppose it would require vigor and sacrifice on the part of their constituents.

A continuation of this atmosphere can only bring disasterin two years, or five, or ten.

Out of this disaster, perhaps we will rebound to be a great nation, for we are yet young enough to have in our memory the case history of our forebears who

wanted nothing from government save a forum in which to arrive at majority agreement.

Let each man who takes money from his government understand: he takes it not from my government; he takes it from meand you.

The authors of the JOHN FRANKLIN LETTERS have projected a curve. The curve is tending downward. The writing is fact, and fear. Not until 1989 will we know how much of it is fiction.

Lyle H. Munson

President, The Bookmailer Inc.,

Distributor of

The John Franklin Letters

PREFACE

July 17, 1989

The title of professional historian has only recently been restored to academic respectability, and it is easy to see why the term was held in suspicion for so long a time. A professional historian must be one whose profession, by definition, is historynot the writing of popular literature, and above all, not the supporting of political theory by polemics or special pleading. In the heyday of the liberal intellectual, half a century or more ago, much of the history written by the professionalsmen of tenure at the foundations and universitieswas a sad mixture of social science and the political and ideological involvement of the historians themselves. Not only did they both consciously and unconsciously put forward the most dubious and challengeable sort of Freudian and Marxian notions as to human aim and motivationthey also frequently supported their assertions with the flimsiest sort of documentation, such as clippings from partisan newspapers and quotations from the public speeches of the very politicians with whom they sympathized. To state a debatable premise as though already established by unassailable authority meant the downfall of logic. It also meant, after a time and for a time, the downfall of the United States of America.

Now we again know that the only truly professional historians are those who work from primary sourcesdocuments of literal fact recorded by participants. Like all truths, this is nothing new, and the conscientious American historian has never had any lack of such primary material. Ours has always been an educated people and above all an articulate people. From the time of the first chronicles of Virginia and New England, we have had observant citizens recording what they saw, what they experiencedthe what happened which is the only material of real history. An early example which comes to mind is the correspondence of Captain Nathaniel Wade and Lieutenant Joseph Hodgkins to their home people in the first American Revolutionary War. Libraries have been filled with the diaries and memoirs of participants in the American Civil War. And so it has gone right down to the singular series of events which brought about the legalistic suspension of the authority of the American people over their own affairs within their own borders, the subsequent widespread resistance to international bureaucratic rule, and the final ousting of the interloping Buros, as they were known, which took place only thirteen years ago. Many a carefully written record of the period of underground resistance in the United States remains to be studied. There are the records of the Ranger organization, as the patriot military forces were called. There are private diaries and notes in abundance, many of which are still to be subjected to scholarly collation. And most valuable of all, there are letters which were exchanged by patriots during the period of the subterranean American resistance to the Buros rule. Since the mails of the short-lived North American Peoples Anti-Fascist Democracy were about

as private as a bulletin board, the correspondence which now has importance to historians was almost entirely that which went from writer to recipient by Ranger courier service. How this service was sometimes interrupted, and the sickening cruelties which followed, stands for all time as a reminder of mans capability for good and evil. And from our present vantage point in time, the various underground letters also stand as impeccable documents of history.

No set of such letters which I have examined seems to tell the story of the time more completely in brief space than those which I have edited into the present volume. Let me give the background of this correspondence and then step aside. The John Franklin papers were willed to the University of Illinois by their recipient, Mr. Jacob Semmes Franklin, who died in 1980 at the age of ninety-three. Jacob Semmes Franklin was a life-long farmer in Central Illinois, working and living on acres which his own grandfather had originally plowed. Throughout the period of the liquidation of the United States government he stood firm as a patriot and his farm was often the center of secret Ranger activities. However, old Mr. Franklins activities are only casually reflected in this correspondence, which came to him from a nephew, John Semmes Franklin, who lived in the East and who was in the Ranger movement, and attempted to keep his uncle informed of happenings in Washington, at United Nations headquarters, and elsewhere, during the years preceding the rise of the Buros and the destruction of the sovereignty of the United States. Now, with the virtue of hindsightor historical perspective, as we scholars call itwe see how accurately John Franklin assayed the events of his time

and how clearly he saw where we were going. In reading these letters to his uncle, we can marvel equally at his clear sightshared by a fewand the blindness of others, shared so tragically by so many.

I should add that John Semmes Franklin was born in 1920 in Chicago, Illinois. The father died when the boy was only three years old, and he spent the next thirteen years of his life on Jacob Franklins farm, which accounts for the close bond between nephew and uncle. John Franklin served in the Infantry in World War II, participating in the campaigns of the First Division. In the Korean police action, John Franklin was concerned with long-range penetration operations, and later worked on certain confidential projects in the Far East, as is mentioned in one of the early letters. When the uncle died, John Franklin returned to the farm, where he himself died in 1984, at the age of sixty-four.