BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Omar Khayym: a New Version

Avicenna on Theology

Sufism

The Spiritual Physick of Rhazes

Modern Arabic Poetry

The Rubyt of Omar Khayym

The Rubyt of Rm

Persian Psalms

Immortal Rose

The Cambridge School of Arabic

Pages from the Kitb al Luma'

The Tulip of Sinai

Fifty Poems of fi

Asiatic Jones

Kings and Beggars

Modern Persian Reader

Introduction to the History of Sufism

British Orientalists

British Contributions to Persian Studies

Specimens of Arabic and Persian Palaeography

The Book of Lovers

The Library of the India Office

The Book of Truthfulness

Poems of a Persian Sufi

The Doctrine of the fis

The Mawqif and Mukhabt of Niffari

Majnun Layla

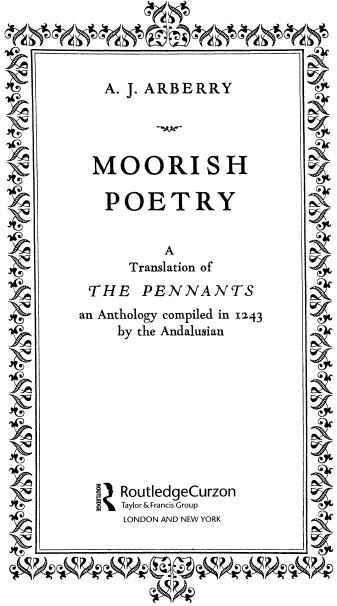

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED BY

THE SYNDICS OF THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

1953

Reprinted By RoutledgeCurzon In 2001

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

London Office: Bentley House, N.W. I.

American Branch: New York

Agents for Canada, India, and Pakistan: Macmillan

ISBN 0-700-71428-6 (hbk)

ISBN 9780203037317 (pbk)

INTRODUCTION

THIS volume is a translation of an anthology of Moorish poetry compiled in the year 12,43 of the Christian era (641 by Moslem reckoning). The author was a certain Ibn Said al Andalusi, a native of Alcal la Real in southern Spain, to day a township of some 30,000 inhabitants, lying in mountainous country to the north-north west of Granada, almost midway between that city and Jan. Born of a cultured family and educated in Seville, he travelled extensively in eastern Islam; the present book was actually written in Cairo. After visiting Damascus, Mosul, Baghdad, Basra and Mecca, Ibn Said entered the service of al Mustansir the ruler of Tunis; later he made a second eastern tour, and died at Damascus in 12,74 (or, accord ing to another account, at Tunis in 12,86). He wrote a considerable number of books, the most celebrated being a history of western Islam.

The text of this anthology, the full Arabic title of which means The Pennants of the Champions and the Standards of the Distinguished, was edited in 1942 by my eminent colleague Professor Emilio Garcia Gomez of Madrid. His edition, based upon a unique manuscript, is a monument to that wide scholarship and literary judgement which have characterized Professor Gmezs numerous contributions to Islamic studies, and the value of the publication is still further enhanced by an illuminating introduction and a careful and annotated translation. The magnitude of my debt to his initiative is too obvious to need further elabora tion. If in not a few places I have differed from my colleague in my interpretation, and occasionally in my reading of the text, it will be appreciated by all familiar with the peculiar difficulties of Arabic poetry that the area of disagreement in understanding a particular phrase or allusion is often considerable, and I do not pretend that my alternative readings are necessarily superior to his.

Ibn Said has arranged his anthology geographically; that is to say, he has grouped the poets according to their birthplaces; the book falls into two main divisions, the first part being concerned with poets born in Moslem Spain, and the second dealing with those who were natives of North Africa (from Morocco to Tunisia) and Sicily. The separate geographical sections are further subdivided according to the poets social status or profession. This is certainly an unusual way of compiling an anthology, but no worse than most other methods; it has its own special interest and value.

The author has exercised, and everywhere demon strates, his personal judgement, first as to the poets selected for quotation, and secondly as to the passages chosen. He was not able to deny himself the immodest pleasure of quoting from his own writings, far more extensively than from those of any other poet; and the entire section devoted to Alcal la Real is taken up with the products of members of his family. This ingenuous peccadillo should not be judged too harshly, given the times in which Ibn Said lived and the social conventions then prevailing; it need not be taken as seriously impugning his literary taste, which appears in general to be of admirable refinement. In any case, he has drawn for us a singularly intimate picture of what a cultured Moor of the thirteenth century considered to be good poetry. Featured in this picture are some of the most famous writers in Arabic literature, as well as many quite obscure poets. It seems doubtful whether more than a small handful of poems have been cited in their entirety; most of the quotations are quite brief extractsin some instances a single stanzafrom what were originally lengthy compositions. In all this Ibn Said is merely following the customary procedure of Arab writers on literary criticism; and the practice of citing extracts can only be explained and justified by reviewing very briefly the nature of Arabic poetry and its development down to Ibn Saids time.

The origins of poetry among the Arabs are as obscure as the beginnings of Greek literature; and just as our knowledge of the latter starts with the finished master pieces of Homer, so our record of the former commences with a number of creations already fully mature in style and language. Homers perfect hexameters re mained for fifteen hundred years the model of prosody in its kind, until stress replaced quantity as the measure of scansion in Greek; the various and varied rhythms discovered by unknown Bedouins at an unknown date, possibly in the fifth century of our era, conceivably earlier, have not been departed from or significantly added to down to the present time. Homer provided all later Greek writers with the legends and myths which constitute their fabric of poetic thought, a fabric enlarged but never even in part demolished through the succeeding centuries. Those legends and myths had to do with gods and heroes; they inspired sculptors and artists not only of ancient Greece, but until this modern age of all the western world. The myths and legends of ancient Arabia were of a very different order; gods and heroes do not figure in them; there is no epic story comparable with the siege of Troy and the wanderings of Odysseus. But if the poetry of pre Islamic Arabia records nothing of ancient heroes, it has much to say of the exploits and virtues of heroic men struggling against a harsh environment and the hostility of their fellow desert dwellers; and if the ancient Arabs saw no visions of water nymphs and dryads, they had keen eyes for the beauty of their camels and horses, whose excellences they never tired of describing. In the town settlements the Arabs also learned to value other aesthetic pleasures, of women and wine and song.

Islam came, and with it a surfeit of warfare, and a great surge of puritanism. The heroic myths and legends of the desert were welcomed into the poetry of faith; the ancient literature was eagerly collected, and passed from oral into written tradition; it was accepted as excellent, and taken as a model of what Arabic poetry should be. These were the themes, and this was the treatment; poetry acquired its grammar and vocabulary. There were right subjects, and right images to portray those subjects. The supremacy of the classical poetry of the desert was the first article of literary faith; the living poet could not go far wrong if he memorized and strove to emulate those examples. Then the great cities of Damascus and Baghdad revived other less austere memories and fashions; in the teeth of orthodox fury the myths and legends of women and wine and song were accepted into the canon. The vocabulary of poetic images was enlarged and enriched.