The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and

retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in

writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote

brief passages in connection with a review written for

inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

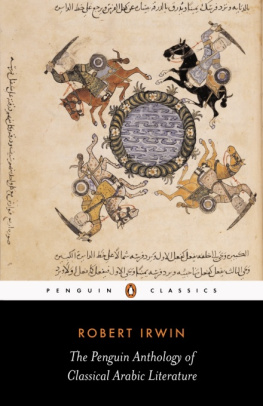

An anthology of translations of the kind which is offered here implies a canon of Arabic literature that is, a selectionof extracts from what the anthologist has judged to be the major authors and the key texts. Certainly, I did not want to involvemyself in the presumptuous enterprise of proposing such a canon. I would have preferred to have followed precedent and takenguidance from the choices of earlier anthologies of the same scope. There are no such precedents to follow. Earlier anthologies(for example James Kritzeks Anthology of Islamic Literature, 1964) have not only spread themselves more widely among Arab, Persian and Turkish sources, but have also tended to use their selectedtranslations as illustrations of aspects of Islamic history and social life. In so doing, relatively little attention waspaid to the literary status of what was chosen, although all sorts of lively and interesting theological, historical and geographicalmatter was included. One can learn a lot about Arab life in general from such anthologies, but not very much about Arabicliterature. This book, however, is about literature. How were prose and poetry recited and written down? What were perceivedto be the sources of literary inspiration? What were the various genres and to what extent were they constrained by rules?What were the canons of traditional Arab literary criticism? How did poetry and belles-lettres evolve between the fifth and the sixteenth centuries?

On the one hand, there is rather a lot of poetry in my selection. On the other hand, there is not enough. There are a lotof poems because, in the judgement of both medieval and modern Arabs, it is in poetry that their supreme literary achievements are to be found. Prose literature has, until this century at least, been much lessesteemed. Yet, for several reasons, I have skimped on the poetry. Arabic poetry is much harder to translate than Arabic prose.The medieval essayist Jahiz (on whom more later) went so far as to observe that poems do not lend themselves to translationand ought not to be translated. When they are translated, their poetic structure is rent; the metre is no longer correct;poetic beauty disappears and nothing worthy of admiration remains in the poems. (Rightly or wrongly, he thought that thetranslation of prose posed no special problems.) Successful translations of Arabic poetry into English are hard to find and,as we shall see, it is debatable what constitutes a successful translation.

Translation is like a seance with the dead and what comes out on the planchette will often read like urgent nonsense. TranslatingArabic poetry is peculiarly difficult. For now, it is sufficient to observe that the way the Arabic language works means thatit is very much easier to find rhymes and therefore to produce long odes with a monorhyme in Arabic than it is in English.Additionally, the Arabic metrical system is quite different from that used in English poetry. Faced with these problems, mostEnglish translators have abandoned any attempt to echo the original rhyme and metre in their translations. Even then, theArab poets penchant for double entendres and other forms of word-play have given translators considerable problems. Satisfactory prose translations have been relativelyeasier to find though only relatively, for some of the grandest pieces have been written in a prose which is bombastic,rhythmic and rhyming, and therefore hard to mimic in English. Some major Arab authors appear never to have been translatedat all.

For both prose and poetry, I have drawn on a wide range of translations by academics, poets and private scholars working overa long period of time. Some translators have succeeded in giving their work an accessible, modern feel, so that for example the ninth-century caliph and poet, Ibn al-Mu'tazz, may appear to speak directly to a contemporary sensibility. Other translatorshave, wittingly or unwittingly, rendered the medieval Arabic into a decidedly archaic English; but this too has somethingto recommend it. When a twentieth-century Arab (or for that matter a tenth-century Arab) reads a pre-Islamic ode, he is rarelyreading something that speaks directly and unproblematically to him. Rather he is struggling with verse that is archaic and frequently obscure in vocabulary, imageryand technique. As Warren T. Treadgold, the translator of Shanfaras pre-Islamic ode, the Lamiyyah, pointed out, that poem is not only nearly untranslatable into English but nearly unreadable in Arabic. From the eighthcentury onwards it was common for poets to produce works which were deliberately archaic, as they pastiched sixth- and seventh-centurythemes and made use of an obsolete vocabulary based on a life in the nomadic desert which the poets in question had not actuallyexperienced. To render such poems into a breezy modern English idiom which is directly accessible to the average reader is,then, to perform a curious service. There is a sense in which a good translator is working not so much on the text, but onhis reader. So the translator of a medieval Arab text is implicitly translating his reader into an Arab, but, as has beensuggested above, a difficult choice still has to be made: what kind of Arab? A seventh-century Arab, a tenth-century Arab,or a modern Arab? And behind this strategic decision, there are, of course, other decisions which will have to be made onechoice merely masking the next in line.

A translator may well be successful in translating the words, but this cannot mean that he has translated the associationsthat those words had for their original audience. For a Western readership, saliva and salivation are likely to be associatedwith spitting, and, perhaps, the dissemination of disease, incontinent drooling, or a response to a dinner bell. But, as thelate Professor A. F. L. Beeston pointed out in his fine selection of translations from the poems of the 'Abassid poet Bashshar,saliva (riq) occupies a privileged place in the Arabic vocabulary of love. A poet is more likely to speak of his beloveds saliva thanof her kiss. Similarly, he is more likely to refer to her teeth than to her smile. For a Western readership, the ostrich maysummon up various associations: the well-known passage in the Book of Job beginning Consider the ostrich ; ostrich farmsand ostrich steaks; childhood visits to the zoo; above all, the foolish birds habit of putting its head in the sand whenthreatened by any peril. But the ostrich (na'am) once abounded in the Arabian peninsula and mention of this bird would summon up a quite different range of associations inthe mind of someone steeped in ancient Arabian poetry or in the techniques of the desert hunt. Indeed, the early Bedouin didnot regard this flightless creature as a bird at all; rather, it was a relative of the camel. Ostriches were ridden by desert ogres. The Ostrichwas a constellation of stars in Sagittarius. To ride the wing of a ostrich was to devote oneself wholeheartedly to something.Above all, the ostrich was the image of cowardice and therefore the tenth-century poet al-Mutanabbi compares the retreatingByzantine emperor to an ostrich. The Western reader may not be aware of this range of associations and, of course, the sortof point that has just been made about ostriches could also be made about toothpicks, lupins, hunchbacks, monasteries, oralmost anything.