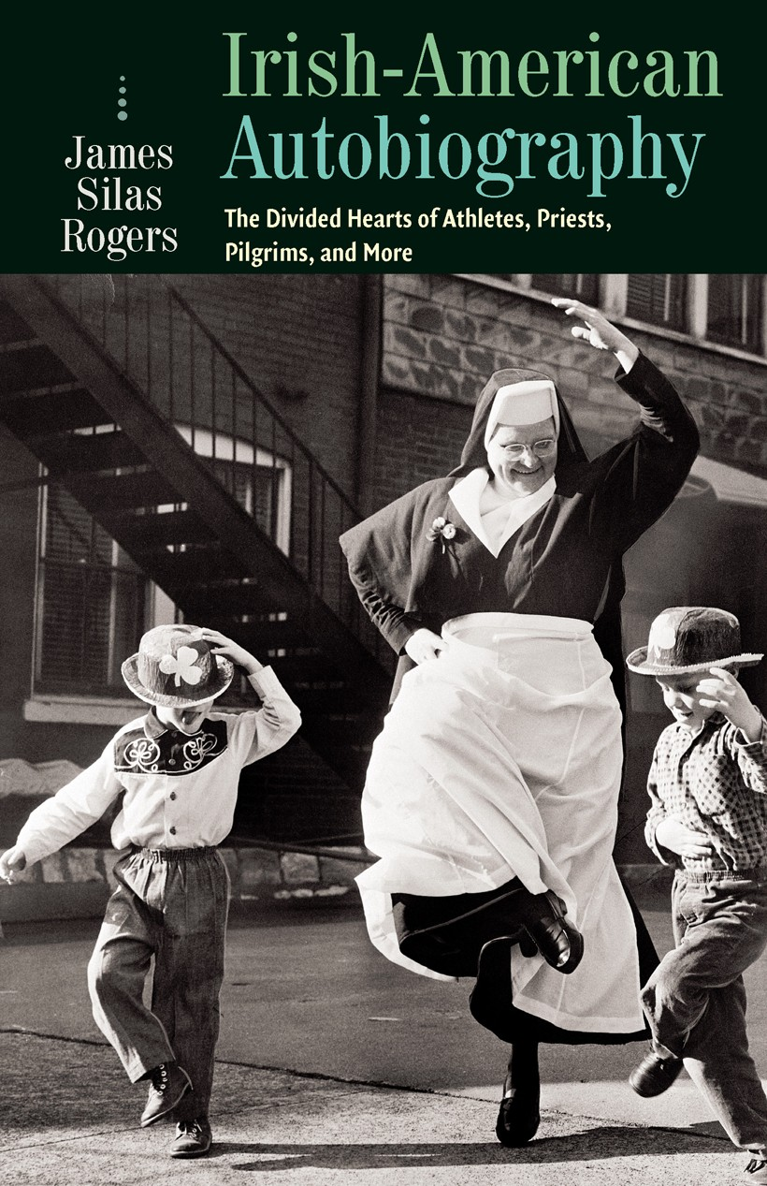

Introduction

The Ethnic Fade That Never Quite Happened

I admit thathowever modest its contributions to the study of Irish-American writing may prove in the endI do look on this book with a bit of a valedictory spirit. Because its subject is, after all, Irish-American autobiography, I will indulge in a small bit of autobiography by way of introduction.

This project has been a long time a-brewing. In 1976, in the opening flourish of the roots phenomenon, I hit on the idea of doing Irish Studies as a self-designed undergraduate major (mostly because I was taking incompletes in all the other classes). Four years later, things took another turn when I went to my first meeting of the ACIS, the American Conference for Irish Studies, hosted by the great historian Emmet Larkin at the University of Chicago. In the company of those titanic, foundational scholars I felt like a kid in a World Series locker room. Though it was nearly fifteen years before I presented my first paper at an ACIS gathering, all of the chapters that follow began life in that venue.

Some years later, I began working as a staff writer for the Irish American Cultural Institute, an anomalous organization that later decided its future lay in New Jersey, a move I was not willing to make. But Ireland had its hooks into me, and since 1996 I have been employed by the University of St. Thomas as managing director, and now director, of its Center for Irish Studies. In other words, I have been lucky enough to spend most of my adult life working in or near the world of Irish Studies.

At a very deep level, I truly do believe that all good writing is personal: some of the works discussed here are old friends, and a few of these books were transformative.

From a historians perspective, autobiographies and memoirs can be problematic sources. From a literary perspective they are frequently irresistible. The project of this bookan attempt to track the shifting meanings of Irishness in America, as those meanings found expression in memoirsis a topic that emerges from a history of its own. One part of that history is the rise of autobiography itself as a subject of study. Memoirs, with which we are now awash, were a stepchild in the formal study of literature until very recent times. In terms of ethnic autobiography, Alex Haleys Rootsnot coincidentally, a book that appeared in 1976, the year of Americas great retrospective of the bicentennialand the television series that followed, was in every sense a game-changer.

Another and perhaps even more basic part of the background to this book is the arrival of Irish America as a subject deserving of attention in its own rightnot an afterthought or appendage to Ireland, but an integral part of its history and culture. The rise of a diasporic model within Irish Studies is a wholly good thing and likewise a recent development; it was not that long ago that discussing Irish America pretty much meant recycling whatever the sociologist Andrew Greeley had written. One of the scholars I met at that first meeting in Chicago was Charles Fanning, who was just setting out on his study The Irish Voice in America. When Fanning received one of his many honors for his scholarship a few years ago, the citation stated that every research act in Irish-American literature begins with his work. This book, which I have presumed to dedicate to Charlie, is no exception.

As the historian Patrick Blessing has observed, there came a point when the story of the Irish in America became the story of Americans of Irish descent.; and the psychic homelessness running under the surface of so many narratives of return in the closing chapter.

Of course, dividedness is usually where autobiography begins: every autobiographers project is to make sense of the warring parts of the self. I happen to hold the opinion that the autobiographical impulse is fundamentally a religious one, in the sense that its purpose is to make meaning; one reason we have lately been living in the age of memoir might be precisely a rejection of the postmodern assumption that our lives are constructed and arbitrary.

Although the extent to which we choose to display our ethnic affiliation is, for most white Americans, a self-determined matter, that identity isnt generally something we get to choose. Elsewhere, I have written of Irish-American memoirists that they are certain that being Irish in America conveys something distinctiveeven if they are not always clear what that distinctiveness is, nor necessarily pleased when they find out. and if your name is Murphy, ORourke, or ONeill, it is all but impossible to go twenty-four hours without someone commenting on your Irishness. How odd, though, that Americas attention to Ireland and Irishness endures long after ethnic and religious out-marriage became the norm; seven or eight decades after the group ceased to be a meaningful voting bloc; and a full half-century after all but a few of the urban neighborhoods that sustained Irish ethnicity were abandoned for the suburbs. The very superficiality of such markers of an identity is quite possibly part of what contributes to their attraction.

A strong statement of such attraction appears near the start of Dan Barrys Pull Me Up, discussed in Island, in a place called Deer Park. It is not a rhetorical question: helping to piece together the narrative of our lives is exactly the purpose of autobiography. Ethnically inflected autobiographies are especially good at describing that process. The general trajectory of the books discussed here reveals that, the further away the writers are from the immigrant generations, the greater their interiority. Irishness in America becomes a sort of found object, abstracted from its contexts, and the challenge of discerning its meaning turns inward, a matter of personal reflection.

Thus, it is helpful to keep in mind the distinction made by Kathleen Brogan in Cultural Haunting: Ghosts and Ethnicity in Recent American Literaturea book that, by the way, pays no attention at all to Irish-American writingbetween ethnographers and heirs. Ethnographers, in this schema, seek to describe characteristics and the stuff of a cohering subculture (food, clothing, holiday rituals, and the like) in which the author is immersed by birth or by a commitment to research. Heirs, on the other hand, engage in a more active process of, as it were, inventing an ethnic identity out of scattered knowledge and interrupted traditions (or nakedly constructed ones, such as Kiss Me, Im Irish! buttons). This book is about heirs.

In some cases, my goal in this volume has been merely to call attention to a book that is deserving of renewed attention, or even of attention, period. There are some fascinating works waiting to be discovered, none more worthy of a second look than Barbara Mullens Life Is My Adventure of 1937 (. Winston Churchill once said that no man ever wrote a boring autobiography; he obviously hadnt read many lives of priests. And yet these inept memoirs, too, speak to the larger inquiry that knits together all of these chapters: the task of understanding the various meanings of Irishness in America.