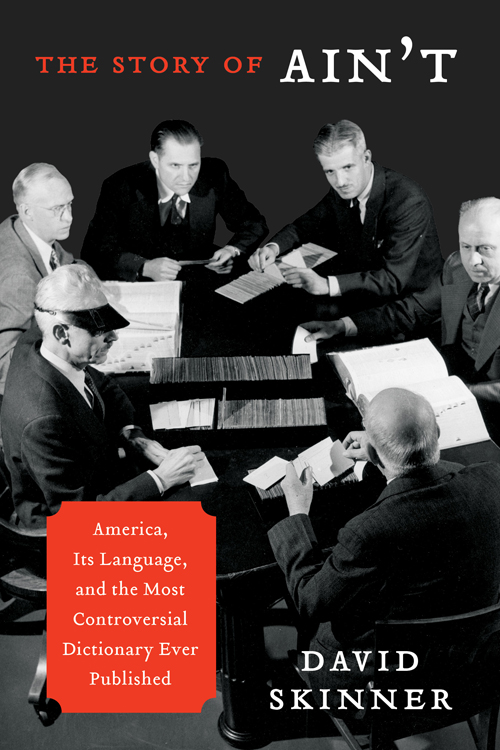

The Story of Aint

America, Its Language, and the Most Controversial Dictionary Ever Published

David Skinner

For my wife, Cynthia

controversy, n. Dispute; debate; agitation of contrary opinions. A dispute is commonly oral, and a controversy in writing. Dispute is often or generally a debate of short duration, a temporary debate; a controversy is often oral and sometimes continued in books or in law for months or years.

Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language , 1828

Contents

W hen I started working on this book about Websters Third and what may be the single greatest language controversy in American history, I envisioned using the occasion to offer my own take on what happened. With all the evidence laid out, I would get to say who was right and who was wrong. In the process, I was going to air many, many important thoughts about language and usage, and you, the reader, were going to be very impressed.

While researching this story, however, I became more interested in what brought about this controversy. Put it this way: Why did Americans in 1961 become so exercisedso iratethat several otherwise sane and distinguished persons said a mere dictionary, however imperfect, represented nothing less than the end of the world?

Controversy wasnt what Noah Webster had envisioned when he published his groundbreaking An American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828, which he hoped would unite his countrymen culturally and politically. And a century laterlong after G. & C. Merriam Company had lost its exclusive right to the Webster name, giving rise to other so-called Websters dictionarieswhen Websters Second was published to general acclaim in 1934, it didnt seem likely that panic and controversy would one day stalk the Merriam-Webster brand.

But a lot changed between 1934 and 1961, obviously. There was the Great Depression, the New Deal, and World War II, all of which left their historical fingerprints on the fast-expanding lexicon. Movies, radio, and television came to the fore, contributing not only new forms of entertainment but new words to describe them. The role of women changed, the baby boom started, the Kinsey reports were published, rock n roll was invented. Cars and roads multiplied. The civil rights movement began.

The idea of America changed. American culture became popular, and serious culture was popularized. The language of Americans went from being a source of modesty to a source of pride, and mined for literary and scholarly purposes. More Americans became more educated and spoke and wrote like educated people speak and write. Feelings about proper usage changed.

Everywhere you looked there was evidence of progress, but always with a glint of darkness. One war gave way to the next, as science assumed a great and sometimes tragic role in society and world affairs. Its influence could even be felt in the humanities, now a collection of second-place disciplines with seemingly inferior standards of knowledge.

And somehow it all contributed to one of the most delicious bouts of accusation, blame, and name-calling ever to be witnessed outside of reality television and the United States Congress. But why? Well, there were many factors. Pride, ignorance, and the profit motive for starters. And, of course, much of it had to do with how we speak and write and what we think of other peoples speech and writing.

L anguage is the ultimate committee product. The committee is always in session and, for good and bad, every speaker is a member of the committee. But I could not write a book about every speaker of American English in the first half of the twentieth century. So I settled on a discrete cast of characters, whose lives, thoughts, and words not only presaged the controversy over Websters Third but also document, to varying degrees, changing standards in American language and culture.

This parade of individualsmore than any attempt by me to offer the last word on whether it is okay to split an infinitive or to use aint in polite conversationmakes up a large part of this book. The other part of this book describes the making and unmaking of Websters Third : how the editor Philip Gove sought to build a modern, linguistically rigorous dictionary and how his criticsfrom the New York Times to Dwight Macdonald to James Parton and the American Heritage Publishing Companysought to destroy it.

The Story of Aint trails from Commencement Weekend at Smith College in 1918, when William Allan Neilson, the editor of Websters Second , was sworn in as the schools new president, accompanied by his mentor, the legendary former Harvard president Charles William Eliot, through the slangy 1920s and Prohibition and the construction of the Chrysler Building in New York City as the young Fortune writer Dwight Macdonald watched from a nearby window. Then it proceeds through the Great Depression and the progress of the new linguistics as it sought to examine American English objectively while American writers such as Zora Neale Hurston and John Steinbeck sought to capture the American vulgate on the literary page. Then it marches through World War II, a war of technology and management and astonishing death tolls, all of which make enormous contributions to the standard language, and into the 1950s as literary intellectuals begin to assess what has been wrought in the American language by the increase in education, by the war, by the political turmoil stretching back decades, and by those scholars trusted to know the most about grammar: linguists. All this leads up to the making of Websters Third and the wild, unexpected controversy that came to life.

Throughout, I take particular interest in the efforts of individuals and groups to bring others around to their point of view. The arts of persuasion and polemic must be considered if we are to learn how this disagreement took shape and then festered, only to blow up on so innocent an occasion as the publication of a new dictionary. And while I take a close look at the general issue of communications (ugh, I know, its one of those 1940s words that sound like a piece of machinery, but it is a major part of The Story of Aint ), this tale is, in fact, told historically, aided especially by documents that show us how the editor of Websters Third thought about language and what he thought about dictionaries.

T hey say it is better to pronounce aunt like art. That its sometimes okay to split your infinitives to, you know, avoid ambiguity. But okay is strictly colloquial. Snide is always slang, and alright is in wide use but not considered polite. Dirty words they never use or acknowledge. And aint they say is dialectal, illiterate.

Who are they? Their names change from one era to the next, but just now they were the Editorial Board of the G. & C. Merriam Company, and they were at the Hotel Kimball in Springfield, Massachusetts, attending a dinner to celebrate the publication of Websters New International Dictionary , Second Edition, Unabridged.

It was June 25, 1934, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt occupied the White House, but few Americans knew their president was bound to a wheelchair. In Hollywood, the actress Mae West was trying to make her film It Aint No Sin , which after the censors were done with it was called Belle of the Nineties . A federal court had recently ruled it was legal to sell copies of James Joyces Ulysses in the United States. For more than a dozen years the novel had been banned due to its earthy vernacular and lewd material, beginning with a scene involving masturbation , which Websters Second defined with a good whiff of Sunday school as onanism; self-pollution.