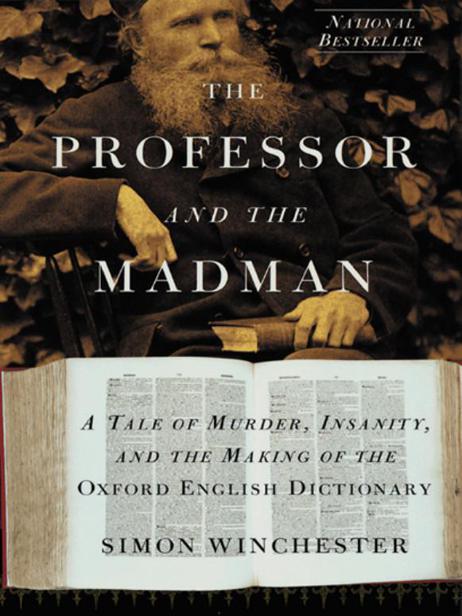

THE

PROFESSOR

AND THE

MADMAN

A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making

of the Oxford English Dictionary

Simon Winchester

To the memory of G. M.

CONTENTS

Mysterious (mist

ri

s), a. [f. L. myst

rium M YSTERY + OUS . Cf. F. mystrieux .]. Full of or fraught with mystery; wrapt in mystery; hidden from human knowledge or understanding; impossible or difficult to explain, solve, or discover; of obscure origin, nature, or purpose.

Popular myth has it that one of the most remarkable conversations in modern literary history took place on a cool and misty late autumn afternoon in 1896, in the small village of Crowthorne in the county of Berkshire.

One of the parties to the colloquy was the formidable Dr. James Murray, the editor of the Oxford English Dictionary . On the day in question he had traveled fifty miles by train from Oxford to meet an enigmatic figure named Dr. W. C. Minor, who was among the most prolific of the thousands of volunteer contributors whose labors lay at the core of the dictionarys creation.

For very nearly twenty years beforehand these two men had corresponded regularly about the finer points of English lexicography, but they had never met. Dr. Minor seemed never willing or able to leave his home at Crowthorne, never willing to come to Oxford. He was unable to offer any kind of explanation, or to do more than offer his regrets.

Dr. Murray, who himself was rarely free from the burdens of his work at his dictionary headquarters, the famous Scriptorium in Oxford, had nonetheless long dearly wished to see and thank his mysterious and intriguing helper. And particularly so by the late 1890s, with the dictionary well on its way to being half completed: Official honors were being showered upon all its creators, and Murray wanted to make sure that all those involvedeven men so apparently bashful as Dr. Minorwere recognized for the valuable work they had done. He decided he would pay a visit.

Once he had made up his mind to go, he telegraphed his intentions, adding that he would find it most convenient to take a train that arrived at Crowthorne Stationthen actually known as Wellington College Station, since it served the famous boys school situated in the villagejust after two on a certain Wednesday in November. Dr. Minor sent a wire by return to say that he was indeed expected and would be made most welcome. On the journey from Oxford the weather was fine; the trains were on time; the auguries, in short, were good.

At the railway station a polished landau and a liveried coachman were waiting, and with James Murray aboard they clip-clopped back through the lanes of rural Berkshire. After twenty minutes or so the carriage turned up a long drive lined with tall poplars, drawing up eventually outside a huge and rather forbidding red-brick mansion. A solemn servant showed the lexicographer upstairs, and into a book-lined study, where behind an immense mahogany desk stood a man of undoubted importance. Dr. Murray bowed gravely, and launched into the brief speech of greeting that he had so long rehearsed:

A very good afternoon to you, sir. I am Dr. James Murray of the London Philological Society, and Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary . It is indeed an honour and a pleasure to at long last make your acquaintancefor you must be, kind sir, my most assiduous helpmeet, Dr. W. C. Minor?

There was a brief pause, a momentary air of mutual embarrassment. A clock ticked loudly. There were muffled footsteps in the hall. A distant clank of keys. And then the man behind the desk cleared his throat, and he spoke:

I regret, kind sir, that I am not. It is not at all as you suppose. I am in fact the Governor of the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum. Dr. Minor is most certainly here. But he is an inmate. He has been a patient here for more than twenty years. He is our longest-staying resident.

Although the official government files relating to this case are secret, and have been locked away for more than a century, I have recently been allowed to see them. What follows is the strange, tragic, yet spiritually uplifting story they reveal.

Murder (

), sb. Forms: a. I moror, -ur, 34 morre, 34, 6 murthre, 4 myrer, 46 murthir, morther, 5 Sc. murthour, murthyr, 56 murthur, 6 mwrther, Sc. morthour, 49 (now dial . and Hist. or arch. ) murther; . 35 murdre, 45 moerdre, 46 mordre, 5 moordre, 6 murdur, mourdre, 6 murder. [OE. moror neut. (with pl. of masc. form morras ) = Goth. maurr neut.:-OTeut. * murro m :-pre-Teut. * mrtro-m , f. root * mer-: mor-: mr - to die, whence L. mor

to die, mors (morti-) death, Gr.

,

mortal, Skr.

to die, mar masc., mrti fem., death, mrta mortal, OSl. m

ti , Lith. mirti to die, Welsh marw , Irish mar dead.The word has not been found in any Teut. lang. but Eng. and Gothic, but that it existed in continental WGer. is evident, as it is the source of OF. murdre, murtre (mod. F. meurtre ) and of med. L. mordrum, murdrum , and OHG. had the derivative murdren M URDER v . All the Teut. langs. exc. Gothic possessed a synonymous word from the same root with different suffix: OE. mor

neut., masc. (M URTH ), OS. mor

neut., OFris. morth, mord neut., MDu. mort, mord neut. (Du. moord ), OHG. mord (MHG. mort , mod. G. mord ), ON. mor

neut.:-OTeut. * muro -:-pre-Teut. * mrto -.The change of original

into d (contrary to the general tendency to change d into

before syllabic r ) was prob. due to the influence of the AF. murdre, moerdre and the Law Latin murdrum .]. The most heinous kind of criminal homicide; also, an instance of this. In English (also Sc. and U.S. ) Law , defined as the unlawful killing of a human being with malice aforethought; often more explicitly wilful murder .In OE. the word could be applied to any homicide that was strongly reprobated (it had also the senses great wickedness, deadly injury, torment). More strictly, however, it denoted secret murder, which in Germanic antiquity was alone regarded as (in the modern sense) a crime, open homicide being considered a private wrong calling for blood-revenge or compensation. Even under Edward I, Britton explains the AF. murdre only as felonious homicide of which both the perpetrator and the victim are unidentified. The malice aforethought which enters into the legal definition of murder, does not (as now interpreted) admit of any summary definition. A person may even be guilty of wilful murder without intending the death of the victim, as when death results from an unlawful act which the doer knew to be likely to cause the death of some one, or from injuries inflicted to facilitate the commission of certain offences. It is essential to murder that the perpetrator be of sound mind, and (in England, though not in Scotland) that death should ensue within a year and a day after the act presumed to have caused it. In British law no degrees of guilt are recognized in murder; in the U.S. the law distinguishes murder in the first degree (where there are no mitigating circumstances) and murder in the second degree.

Next page

ri

ri rium M YSTERY + OUS . Cf. F. mystrieux .]. Full of or fraught with mystery; wrapt in mystery; hidden from human knowledge or understanding; impossible or difficult to explain, solve, or discover; of obscure origin, nature, or purpose.

rium M YSTERY + OUS . Cf. F. mystrieux .]. Full of or fraught with mystery; wrapt in mystery; hidden from human knowledge or understanding; impossible or difficult to explain, solve, or discover; of obscure origin, nature, or purpose.  ), sb. Forms: a. I moror, -ur, 34 morre, 34, 6 murthre, 4 myrer, 46 murthir, morther, 5 Sc. murthour, murthyr, 56 murthur, 6 mwrther, Sc. morthour, 49 (now dial . and Hist. or arch. ) murther; . 35 murdre, 45 moerdre, 46 mordre, 5 moordre, 6 murdur, mourdre, 6 murder. [OE. moror neut. (with pl. of masc. form morras ) = Goth. maurr neut.:-OTeut. * murro m :-pre-Teut. * mrtro-m , f. root * mer-: mor-: mr - to die, whence L. mor

), sb. Forms: a. I moror, -ur, 34 morre, 34, 6 murthre, 4 myrer, 46 murthir, morther, 5 Sc. murthour, murthyr, 56 murthur, 6 mwrther, Sc. morthour, 49 (now dial . and Hist. or arch. ) murther; . 35 murdre, 45 moerdre, 46 mordre, 5 moordre, 6 murdur, mourdre, 6 murder. [OE. moror neut. (with pl. of masc. form morras ) = Goth. maurr neut.:-OTeut. * murro m :-pre-Teut. * mrtro-m , f. root * mer-: mor-: mr - to die, whence L. mor  to die, mors (morti-) death, Gr.

to die, mors (morti-) death, Gr.  ,

,  mortal, Skr.

mortal, Skr.  to die, mar masc., mrti fem., death, mrta mortal, OSl. m

to die, mar masc., mrti fem., death, mrta mortal, OSl. m

ti , Lith. mirti to die, Welsh marw , Irish mar dead.The word has not been found in any Teut. lang. but Eng. and Gothic, but that it existed in continental WGer. is evident, as it is the source of OF. murdre, murtre (mod. F. meurtre ) and of med. L. mordrum, murdrum , and OHG. had the derivative murdren M URDER v . All the Teut. langs. exc. Gothic possessed a synonymous word from the same root with different suffix: OE. mor

ti , Lith. mirti to die, Welsh marw , Irish mar dead.The word has not been found in any Teut. lang. but Eng. and Gothic, but that it existed in continental WGer. is evident, as it is the source of OF. murdre, murtre (mod. F. meurtre ) and of med. L. mordrum, murdrum , and OHG. had the derivative murdren M URDER v . All the Teut. langs. exc. Gothic possessed a synonymous word from the same root with different suffix: OE. mor  neut., masc. (M URTH ), OS. mor

neut., masc. (M URTH ), OS. mor