Simon Winchester - Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire

Here you can read online Simon Winchester - Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire

For Elaine

The Plan

British Indian Ocean Territory and Diego Garcia

Tristan

Gibraltar

Ascension Island

St Helena

Hong Kong

Bermuda

The British West Indies

The Falkland Islands

Pitcairn and Other Territories

Some Reflections and Conclusions

The world has changed a very great deal since 1984, the year during which I wrote the following affectionate, in many ways rather poignant, and on occasion sentimental account of my wanderings to and around the British-run relics of the greatest of all modern Empires.

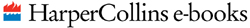

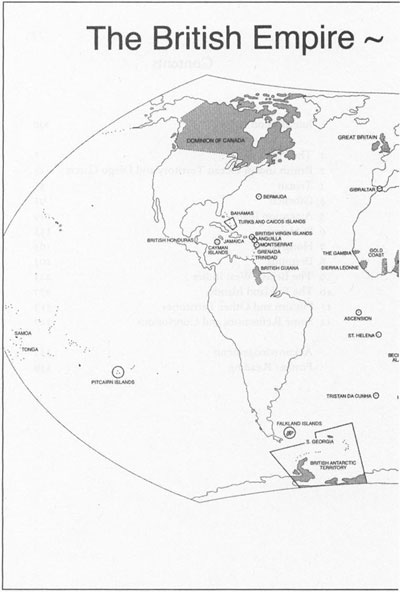

The small and curiously discrete world of which I was writing then has changed physically, of course. The tiny Imperial assemblage I was then able to describe has shrunk, at the very least by the removal of the territory of Hong Kong from the rolls. I stood in the hot rain that June night in 1997 and watched the Union flag come down, and as midnight struck and the Chinese victory fireworks started to erupt, so I watched as Britannia sailed away for London, taking with her the colonys last Governor and his Prince, and a clutch of women standing at the taffrail, in tears. Even putting sentiment deliberately to one side, it would be idle to suggest that night was anything but unbearably moving.

The Imperial population, if we can still call it that, evaporated with that single and long-expected act of retrocession, from the full six million it was back then to just the few tens of thousands of people who remain under Londons weary supervision today. A gathering of distant places which still had some slight significance before that June nightwhen, quite literally, the sun did not set on the British Empirewas reduced at the stroke of a midnight bell to not much more than a fistful of dust.

The world beyond the relict Empire has changed profoundly, too. The titanic stand-off between what we liked to call the superpowers was, in 1984, soon and quite unexpectedly to be over; today only one such power remains, and the totalitarian ideology that underpinned the other, and which had such relevance to many of the tiny places in the world that were once run from London, has now all but vanished. In 1984 a place like Ascension Island derived much of its reason for being from the Cold War; it was close enough to the malleable states of West Africa to make it the ideal location for electronic spies seeking to monitor the increasing threat of Marxism. With the fear of that ideology all but vanished, there now seems little point to the populated existence of the island (after all, the island was barely populated before we seized it) nor to Britains continuing possession of it.

Much else has changed besides. The public attitude towards Empire and to the very notion of Imperialism itself has undergone a swift metamorphosis over the past two decades. Post-colonial literature, already in 1984 a small but well-established genre, has since swollen to a flood, and has been joined by a canon of scholarly studies emphasising the point that, no matter how benevolent and well-intentioned the colonising powers may have thought themselves to be, their effect upon the world was ultimately to lead to the gravest of ills. Affection and poignancy are rarely to be found in todays writings about a kind of governance that is now regarded as having been politically most incorrect; sentiment, never the best lens through which to view anything, is these days a wholly inadvisable means of looking at past Empires, which appear to deserve only the cold gaze of the post-structuralist sceptic.

There are a number of obvious reasons behind the burgeoning of these new ways of thinking about Empire. Perhaps the most important is the flourishing of journalism and literature on the subject by post-colonialist authorsthe old guard like V. S. Naipaul, Chinua Achebe and Derek Walcott, and the more recent such as Salman Rushdie, J. M. Coetzee and Vikram Sethwhose experiences and memories of being part of the enginework of colonial subjection have found a wide and admiring audience. The fact that Naipaul is now a Nobel Prize winner underscores the wide admiration for his specific achievement in giving a voice to the Imperially ruled, rather than to the Imperially ruling, classes.

Then again, the rather more widely appropriated culture of repudiation, which lies at the heart of so much present-day art and literature, has enabled many to challenge the comfortable old assumptions of white-run Empire simply because they are comfortable and old and white, and has elevated anti-colonialist sentiment to the status of high fashion. Edward Said, the noted and prolific Palestinian scholar at Columbia University, who wrote the groundbreaking 1978 work Orientalism and went on to publish Culture and Imperialism in 1993, has long been a standard-bearer for the new movement. Few are the students who do not regard his trenchant views of the cruel and crabbed legacies of colonialism as having the heft and authority of Holy Writ.

But there is one further reason, rather less easy to discern, behind the change.

There is currently an uncomfortable feeling abroad, a feeling that was not recognisable in 1984 and is still not fully recognised today, which in essence holds that an Empire of quite another sortor some kind of phenomenon that we feel like calling an Empireis stealthily and subtly returning to centre stage. We have an uneasy feeling that whatever this new entity is, it is before too long going to exert an unacceptable and undesirable influence over the world, and that the entire cycle which we thought had ended with the slow collapse of all the great sea-borne European Empires during the three decades following the Second World Warthe British Empire pre-eminent among themis in fact beginning all over again.

The phenomenon of which we have such grave suspicion has many names: globalisation is currently the most popular and thus the most familiar. Informal Empire is anotherthe notion that since the old, formal Empires are all now dead, since the systems of unelected Governors and Viceroys and District Commissioners have all passed away, what replaces them is an unstructured kind of imperium, with on the one hand a slew of new and similarly unelected rulers, which in this case are banks, corporations and brands, all operating without restriction in a new and economically borderless world, and on the other hand a vast and disparate body of subject peoples, who are in increasing numbers bound to make use of these banks, corporations and brands and are kept in thrall to them unwittingly, but firmly kept there nonetheless.

The benefits of globalisation are proclaimed vociferously by the banks and corporations who are its prime beneficiaries: economies of scale mean that consumer products become cheaper and more widely available; bureaucracy crumbles in the face of corporate-directed efficiency; access to goods and services is more widespread, more democratic , the standard of living everywhere improveseveryone floats higher on an ever-rising tide of global prosperity.

But the darker side of the phenomenon, less readily observable, is what worries many. That the world is becoming increasingly ordered by unelected and faceless figures in distant (and most commonly American) corporate headquarters, figures who are answerable only to the shareholders in the country which is their base of operations. That there are fewer and fewer controls on those global operatorsfor under whose law, exactly, do they operate?to limit unscrupulous and inhumane behaviour. That the less powerfulthe employee in a Third World nation, working under contract for some distant American company whose responsibility is limited by distance and by adroit corporate lawyerscan be oppressed and cheated and denied rights, without anyone to notice or complain. That indigenous businesses can so easily be forced under, unable to stand the competition from the corporate super-giants whose growing share of world trade seems unstoppable, and whose ruthlessness is glorified by managers, who see it as essential for success.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire»

Look at similar books to Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.