2000, 2010 by Ken Light

Introduction 2000 by Kerry Tremain

All rights reserved

The text in this book is based on interviews conducted by Ken Light with support from an Erna and Victor Hasselblad Foundation grant.

The interviews were edited by Ken Light, Melanie Light, and Kerry Termain.

COPY EDITOR: Lise Sajewski

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Light, Ken.

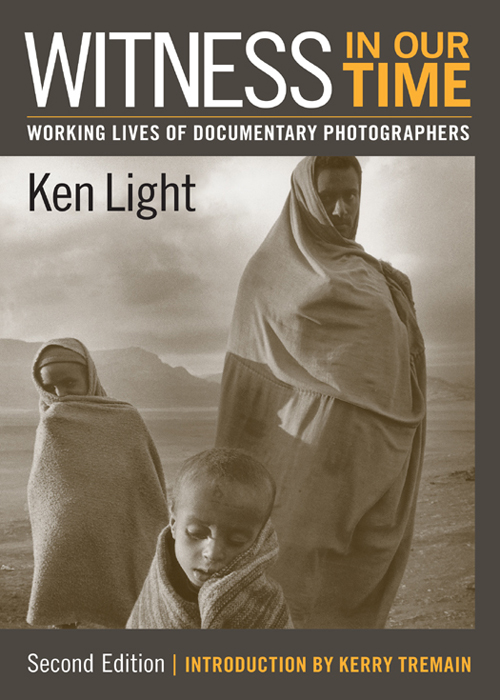

Witness in our time : working lives of documentary photographers / Ken Light ; introduction by Kerry Tremain. 2nd ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58834-306-2

1. PhotographersInterviews. 2. Documentary photography. 3. Photojournalism.

I. Title.

TR139.L54 2010

770.922dc22 2010031643

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually, or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

v3.1_r1

For Stanley Light, my father,

who gave me my first camera and taught me about the human condition,

and Melanie Light, my wife,

who has been patient, reassuring, and wise.

Contents

Introduction: Seeing and Believing

KERRY TREMAIN

Afterword: Witness in Our Time

KEN LIGHT

Acknowledgments

The second edition of Witness in Our Time would not have been possible without the support, comments, discussion, and editing by Melanie Light, my wife and partner. She generously allowed me to bounce ideas off of her, argue with her, and always gave wise, thoughtful feedback despite my stubbornness. Without her support this book would not have been possible. My daughter, Allison, was always present with a smile and a How was your day, Daddy? and then attentively listened to my reply, which is a wonderful gift from a teenager busy with her own active world.

A generous grant from the Erna and Victor Hasselblad Foundation originally supported my travel and my time to conduct interviews with the photographers, and a grant from the National Press Photographers Research Foundation (NPPA) gave a much-needed boost. Without this support I might have never originally undertaken this project.

The first edition could not have happen without my colleague and co-conspirator Kerry Tremain, nor would it be in its present narrative form, or graced with such an insightful introduction. As we began this updated edition, Kerrys original introduction still rang true. The research he did for the first edition, and his collaboration on the biographies that introduce those interviews made the 2000 edition more readable. Our conversations and his editing skills, passion, and faith in the ideals of documentary photography were a welcome breath of fresh air and made a critical contribution to the books final form.

Many have given to this work. Amy Pastan, my former acquisitions editor at the Smithsonian Institution Press, first agreed to the publication of this manuscript and nurtured it into draft form. My thanks to Mark Hirsch, former senior editor at the Smithsonian Institution Press, on whose desk this project landed as a book without a home. His unwavering support restored it back to health and finally to its present form. The first edition editor, Robert Poarch, and designer, Janice Wheeler, both helped create a more dynamic publication.

Over the years, as Witness in Our Time has been adopted by colleges and read by thousands of photo students and documentary photographers, I wondered what would become of this book as huge changes impacted the photo world. To my surprise, Carolyn Gleason, director of Smithsonian Books, asked me if I might revise the book. Christina Wiginton stepped in as editor, and it has been a great pleasure to have such an enthusiastic supporter of this work.

Many thanks to the photographers who took their precious time to answer my questions and who were so very patient, offering photos, reviewing text, and correcting mistakes that can so often happen in a recorded interview.

My students and assistants at University of California, Berkeley Graduate School of JournalismDoreen Bowens, Jill David, Matt Golec, Christina Koenig, Kimberly Lisagor, Matt McClesky, and Sophia Rayhelped with the tedious transcriptions of the recorded interviews and indexing in the first edition. Fortunately Ananda Shorey stepped forward to do the transcriptions in the new edition, and proved to be accurate and quick, making my job that much easier.

My colleagues at the graduate school have continued to inspire me, and Neil Henry, dean of the school, has been a great supporter of the photography program and my work. My intern and assistant Max Cohen has helped me at every turn and given me insights about the next generation. My friend Jay Berg offered his apartment on my visits to New York to use as a home base for some of the interviews.

This book originally started with my colleague and friend Kim Komenich as we bemoaned the lack of a text for our students from which they might gain insight into the lives and work of documentary photographers. Long after we took separate paths toward this goal, he remained a steadfast supporter and cheerleader for this projects completion.

Finally to the readers who have shared this book with others, and to all of those working to keep the documentary tradition alive, thank you.

Ken Light

Thanks to Valerie McGuire for researching the biographies. For reading and commenting on the edits and introduction, thanks to Mike Feeback, Carl Fleischhauer, Melanie Light, Joe Loya, Brad Matsen, Susan Meiselas, Joshua Phillips, Jon Polansky, Barbara Ramsey, Fred Ritchin, Bill Smock, Marilyn Snell, Patti Wolter, and especially to Jane Melnick, who first ignited my interest in documentary photography, and Peter Solomon, master wordsmith.

Kerry Tremain

Introduction

Seeing and Believing

KERRY TREMAIN

I

W hen mujahedin soldiers captured Antonin Kratochvil in Afghanistan, where he traveled in 1978 to photograph their war with the Russians, one of them pressed the barrel of an AK-47 rifle into Kratochvils temple, read his passport, and shouted to the others that their prisoner was born in Czechoslovakia. The mujahedin knew Czechoslovakia. Czechs manufactured Russian guns. The soldier told the photographer he was going to blow his brains out.

Ironically, Kratochvil had risked his life to escape communist Czechoslovakia eleven years earlier. While still a teenager, he had walked to the Czech-Austrian border, a coil of barbed wire in a swath of fine gravel raked to allow the police patrol to track trespassers footsteps. A friend of his had been killed nearby. In the dark he crawled under the barbed wire on his belly. Upright, euphoric, he spit on the Czech side of a stone that marked the border.

In Afghanistan Kratochvil sat silently while a guide he had hired just a few hours before pleaded furiously with them to spare the photographer. He is not a spy; he hates the Soviets. He will tell the world about your revolution. You know my cousin who fixed your truck.

For two hours, the guide begged. Finally, the mujahedin fighter lowered his rifle and freed Kratochvil.