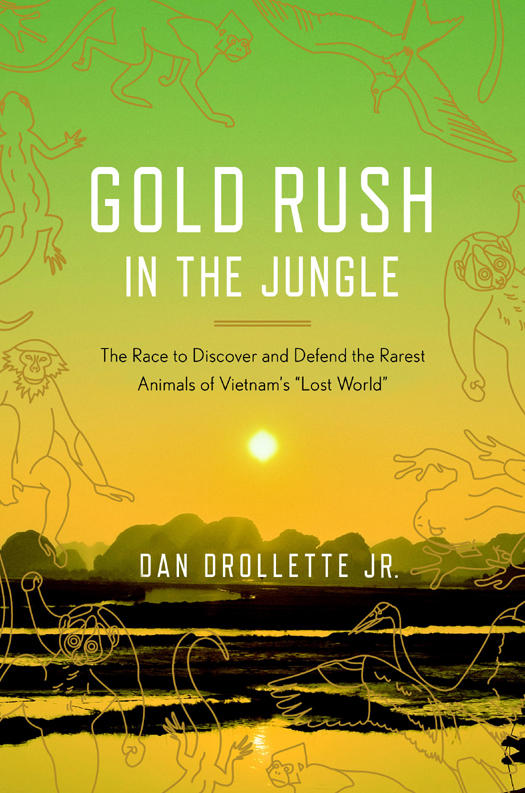

Copyright 2013 by Dan Drollette

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of the materials in the previously appeared in Newsday, International Wildlife, The Sciences, National Wildlife, and Scientific American.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95587-6

by Patricia J. Wynne

Jacket design by Sara Wood

Jacket photograph: Peter Unger

v3.1

To my parents, for instilling in me a love of nature and a sense of curiosity about the world.

Contents

PROLOGUE

Dawn in the Jungle

2010

and Beyond

GLOSSARY

Whos Who Among the Animals

Authors Note

To see beneath both beauty and ugliness; to see the boredom, and the horror, and the glory

T. S. Eliot

The discovery of a new species of wildlife is often the result of multiple strands of competing evidence, chance encounters, accidents, preconception-shattering experiences, and winding, discursive roundabouts. To even begin to describe the situation in Vietnam when it comes to discovering and rescuing new species, I attempted to conduct as many interviews as possible, with multiple sources, concentrating especially on the men and women who sweat it out among the mud and leeches.

To put these fieldworkers immediate, firsthand observations into larger perspective, I sought the viewpoints of those who work at wildlife organizations, zoos, nature preserves, research centers, museums, and universities in other parts of the world, along with the printed record. I have tried to give the big picture vitality by relying upon an abundance of significant detail, telling this wildlife protection story in terms of people, places, and events as opposed to quoting scientific journals or government documents verbatimalthough such publications have been priceless for background.

Whenever possible, I brought in the point of view of a newly emerging generation of young Vietnamese biologists, park rangers, graduate students, and PhD candidates with an interest in protecting their countrys natural heritage. Their input is often overlooked due to the language barrier and the sometimes byzantine bureaucracy involved in working with the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. (For claritys sake and to be in line with conventional Western usage, I have otherwise written the countrys name as Vietnam.)

I chose to focus on wild mammals because that is where researchers have encountered the largest and most spectacular creatures. But I could have just as easily concentrated on plants, fish, insects, amphibians, or bird life.

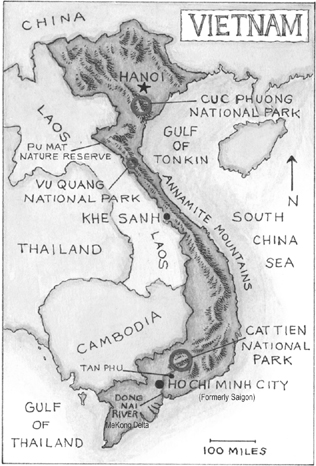

Similarly, I zoomed in on a few key protection programs and parks scattered up and down the country out of the dozens of reserves available, paying most attention to Cuc Phuong National Park and its environs. As Vietnams oldest and best-established nature preserve, since 1962 this place has some of the countrys most innovative wildlife rescue programs, setting the tone for the rest of Indochina.

A few words to those wishing to see for themselves some of the rare and wonderful creatures described here. Parts of Vietnam are striking, but not much of it is in the kind of untouched state that Westerners are used to in places such as Yellowstone National Park. After all, Vietnam has been inhabited by successive waves of people over thousands of years.

Yet biogeographic islands remain, off the tourist trail. Even heavily visited places such as Ha Long Bay have rare and endangered langurs scurrying up and down the rock cliff faces of its islands. You may not be able to see a saola or a kouprey, but you could see one of the last sixty specimens of the highly endangered Cat Ba golden-headed langur.

One last bit of advice: Give yourself plenty of time, and put away the itinerary now and then. One highlight of my last trip occurred simply by sitting in a Hanoi caf and talking to the proprietor and one of the regulars. Id only planned to stop for a brief coffee before embarking on an ambitious two-hour walk to tick off every item in my guidebooks Must-See list of the city. Instead, a quick break turned into a fascinating three hours in which we exchanged pictures, looked at maps, and traded e-mail addresses; I was able to visit the newsroom of the Vietnam News as a result. I never did finish that walk.

Like the cramped, narrow streets of Hanois Old Quarter, the work of wildlife biologists in Vietnam is full of the unplanned and serendipitous, as well as the messy, the crowded, the dirty, and the wonderful.

This is their story.

As a reporter, I have tried to be as honest, accurate, intelligent, and fair as possible; any errors of fact or interpretation are mine.

Prologue

Dawn in the Jungle

This region represents much more than the find of the year; it could be the find of the century.

Colin Groves, taxonomist, Australian National University

It is daybreak in Ninh Binh province, seventy-four miles southwest of Hanoi, and the limestone mountains of Cuc PhuongVietnams first national park, founded in 1962 with the blessing of Ho Chi Minh himselfare just emerging from the mist.

Though it is only five a.m., lights can already be seen in the windows of the farmhouses just outside the park; the buildings traditional thatched roofs, combined with the adjacent neatly tilled rice paddies and abrupt nearby mountains, make the scene look as quiet and still as that on an ancient scroll.

Inside the park, however, the forest is full of sound, from the drone of mosquitoes to the maniacal racket of white-crested laughingthrushes. Loudest of all is a deep-throated huuuu-huuuuuuu-huuuuuuuuuu-huuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu coming from the dense treetops. This is the great call of the gibbon, a long-armed, fruit-eating ape, which human listeners have sometimes compared to a mourning doves cry, managing to be beautiful while mixed with a sense of loss.

Unfortunately, it is a sound fast disappearing from Vietnams forests, at a pace that has accelerated noticeably over the past fifteen years.

One of the few places where you can still hear what Jane Goodall once described as one of the wonders of the primate world is here, just inside the park boundary, at the Endangered Primate Rescue Center (EPRC). Consisting of a five-acre semiwild, enclosed area, the centers roughly circular central compound lies inside a larger perimeter ringed by two outer fences; from above, the series of concentric circles would resemble a dartboard. And in the bulls-eye are 150 specimens of the worlds rarest and most endangered animals, most of which would have been dead but for the efforts of Tilo Nadler (TEE-low NAD-ler)a self-taught biologist who nevertheless went on to become what an eminent zoologist, Colin Groves, described as the unsung hero of Indochina wildlife protection.

There is much to be protected, because just beyond the park lie a series of limestone mountain ridges stretching north to south to form the calciferous spine of Indochina. Known to geographers by the lovely name of the Annamese Cordillera, this mountain range runs the entire length of the country and contains within its valleys, hills, sinkholes, karsts, and innumerable caves something that Oxford University zoologist John MacKinnon described as the lost worldhome to strange, rare animals such as the Asiatic sun bear, the Tonkin snub-nosed monkey, and the clouded leopard.