This book is dedicated to a door that opened in Nashville ten years ago. Stephanie walked through it and changed my life foreverG. L.

For Kate, Emily, Rosa, Annie, and Emmylots of beautiful girls for me to love and photographS. M.

George Lange would like to thank: My mother, Aline; Andrew Lange; Janet and Steve Cook; Scott Mowbray and Kate Meyers; Wendy Snyder-MacNeil; Duane Michals; Aszure Barton; Aaron Siskind; Jeni Britton Bauer; Christine Kullberg; Critt Graham; Annie Leibovitz; Kay Unger; Maggie Hamilton; Glenn Beck; David Mishler; Jeremy Sachs-Michaels; Monika Dabal; Dan Cavey and Karen Smith; Sarah Paz-Hyde; Barbara Griffin; Jane Huntington; and especially my father, who always encouraged me, amused me, and showed me how to get people to disarm in front of a camera. These pictures are a document of our familys love. I thank Stephie, who taught me love in ways I had only dreamed of, and then gave me Jackson and Asher, who fill my cup every day with even more love. That we can share that love with one another is a dream come true. That we can share it with you is a gift.

Scott Mowbray would like to thank: For their help, support, and instruction over the years: Kate Meyers, Rick Staehling, Peter Sikowitz, Jim Baker, Carla Frank, Tom Brown, Dirk Barnett, and Dan Okrent.

Both authors would like to thank: Mark Reiter; Suzie Bolotin, Janet Vicario, and their talented colleagues at Workman; and Peter Workman, who was so enthusiastic and supportive when we first began talking about the book and who we hope would be so proud of what he inspired us to bring into the world.

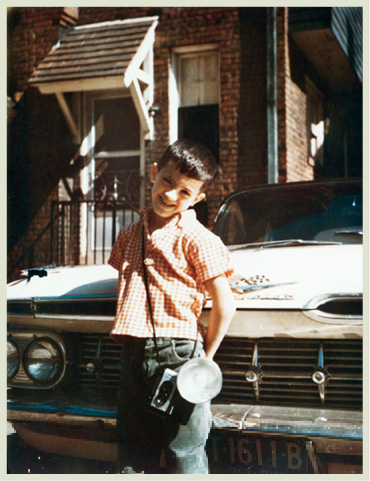

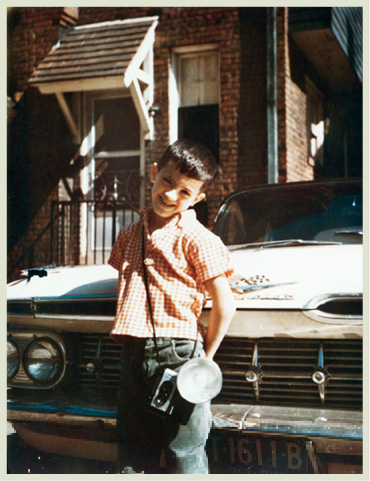

When I have a camera in my hands, good things happen. This was my first camera. It was the key that would open doors to places I could never have otherwise entered.

It all started here, at the age of seven, in my parents driveway in Pittsburgh, standing against their white Chevy, holding a little box camera. I was lucky to have a childhood filled with love, friendship, and community, and from the beginning, I wanted to capture that joy in my photography. From the first pictures I took with that box camera, through the ones I shot for my high school newspaper and yearbook, to the ones I made in art school and throughout my professional careerall my best pictures were born of that early joy. Sometimes I think I have simply tried to re-create with my camera what made me so happy growing up.

My camera has taken me all over the world but, much more than that, it has taken me into myself and allowed me to share what I am feeling. Photography has been a great ride (which isnt over), but for me, the final pictures are never what it is all about. More important, always, is the process of listening, seeing, touching, holding, moving, being still, pushing hard, easing in gently. Photography, Ive learned, can be an excuse to say things you would edit out of a normal conversation, do things you would hold back from doing. It taps into my urgent need to live a life that treats every moment like a gift. Photography is, as Ill explore in this book, all about moments.

After graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design, I showed my portfolio to a teacher and brilliant photographer I loved, Aaron Siskind. He paged through my pictures and said, These are not nearly as good as you are. That set the bar for methe idea that pictures had to be as good as I could be.

In New York I apprenticed with my heroes. Duane Michals, the great art photographer from Pittsburgh, famously said, This photograph is my proof.... Look, see for yourself. Ideas, he taught me, were much more important than exposures. I worked for a German still-life photographer, Michael Geiger, who taught me to be on time for everything: If I arrived one minute early or one minute late I would be fired. You strive, in other words, to always be there for the moment. Then I assisted Annie Leibovitz. During her year between shooting for Rolling Stoneand Vanity Fair, I traveled all over the world with her. That was amazing. Annie was passionate, obsessive, an artist. I learned choreography from Annie. Working, communicating: She had a special rhythm. Throwing myself completely into her work eventually allowed me to discover my own rhythm; this book is also about finding your rhythm.

The day I left Annie I knew I would never assist again. I would either make it as a photographer in New York or find something else. I would go to the top of the Cond Nast building and stop on every floor until I reached the lobby. I never got to the street without an assignment. I learned this crucial lesson: Whenever I really put myself out in the world, I got work. This, I believe, is just as true for personal photographyfor you, in other words: You have to put yourself out in the world. You have to connect.

Taking pictures every day (both personally and professionally), I have created a body of evidence that proves, if nothing else, why I am never bored. The pictures of my family become both my memory and gifts to my children, who will always know how much I have loved every breath theyve taken.

This book, at its heart, is about photographing how things feel rather than what they look like; it is about appreciating all the beauty and passion and love in our everyday lives. It is about seeing that even the most mundane detail can be extraordinary and full of feeling. Yes, photographs that are real and direct in an emotional sense risk being corny, but they can feel like timeless gifts as well. I think of photographs of this kind as kisses: They exist in a brief ecstatic moment and then take on a life of their own.

Being a professional photographer opens doors for me, introduces me to fascinating strangers, takes me out into the world. Many of my most treasured pictures were not taken on assignment, though. Even if they did emerge from my professional work, they were usually shot around the edges of assignments. I take some of my best pictures when everyone breaks for lunch and I keep shooting. When lights are being set up, I am already shooting, looking to discover something new. I am always on the moveand that simple idea, moving, is the subject of one of the chapters in this book.

At home, on the train, at the beach, Im constantly shooting, wanting to capture what I am experiencing, whether its with my camera or my iPhone. Of course, so is almost everyone else in the world. Im convinced that the billions and billions of pictures taken today, the ones straining Facebooks servers, show a hunger to live life more richly. Yet I also see that many people are shooting the surface of things, the way things look. The risk is that by staying on the surface, and using easy digital effects to make our pictures pretty, we risk trivializing how we really experience our lives.

It may seem like a contradiction: that picture-taking can take you deeper into life rather than removing you from it. Doesnt the camera get between you and the thing you are experiencing? Well, it can, but not if you are truly present, as I believe you must be to take beautiful pictures. Philosophers and psychologists use the term being present to describe the experience of consciously living life in the moment, rather than passing through an experience with ones mind on something else. In this time of digital overload, its easy not to be present; its easy to hide, even live, behind the lens, or the screen, in the virtual world. My collaborator on this book, Scott Mowbray, describes spending so much time taking bad pictures of a total eclipse of the sun in India many years ago that he was left with tiny-speck shots of a magnificent celestial event that he had, essentially, missed. Next time, in Indonesia, he put the camera away and just took it all in. Thats why I rarely take pictures of experiences like that. The camera, except in the hands of geniuses like Ansel Adams, is not good at taking in the gargantuan. Im much more interested in the millions of in-between moments that make up the real fabric of our lives. If I did shoot an eclipse, Id shoot the person who was watching it in awe.