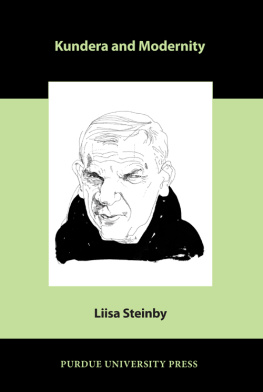

MILAN KUNDERA "LAUGHABLE LOVES"

"Light, wry, and wise." John Skow, Time

Milan Kundera is a master of graceful illusion and illuminating surprise. In one of these stories a young man and his girlfriend pretend that she is a stranger he picked up on the road only to become strangers to each other in reality as their game proceeds. In another a teacher fakes piety in order to seduce a devout girl, then jilts her and yearns for God. In yet another girls wait in bars, on beaches, and on station platforms for the same lover, a middle-aged Don Juan who has gone home to his wife. Games, fantasies, and schemes abound in all the stories while different characters react in varying ways to the sudden release of erotic impulses.

"An intellectual heavyweight and a pure literary virtuoso, Milan Kundera takes some of Freud's most cherished complexes and irreverently whirls them about in acts of legerdemain that capture our darkest, deepest human passions.... The tales in Laughable Loves surprise and illuminate..

.. Kundera's world is complex, full of mockeries and paradoxes. Life is often brutal and humiliating; it is often blasphemous, funny, irritating." Abe Ravitz, Cleveland Plain Dealer

"Milan Kundera offers a very special blend of sympathy and cynicism, irony and affability, that is unmatched in our literature." Thomas Joyce, Chicago Sun-Times The Franco-Czech novelist Milan Kundera was born in Brno and has lived in France, his second homeland, for more than twenty years. He is the author of the novels The Joke, Life Is Elsewhere, Farewell Waltz, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and Immortality, and the short story collection Laughable Lovesall written originally in Czech. His most recent novels, Slowness and Identity, as well as his nonfiction works, The Art of the Novel and Testaments Betrayed, were originally written in French.

ISBN 0-06-099703-6

BOOKS BY MILAN KUNDERA

The Joke

Laughable Loves

Life Is Elsewhere

Farewell Waltz (EARLIER TRANSLATION: The Farewell Party)

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Immortality

Slowness

Identity

Jacques and His Master (PLAY)

The Art of the Novel (ESSAY) Testaments Betrayed (essay)

Milan Kundera

Laughable Loves

Translated from the Czech by Suzanne Rappaport

This book was first published in Czechoslovakia under the tide Smesne lasky by Ceskoslovensky Spisovatel, 1969. It was first published in the United States of America by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1974.

LAUGHABLE LOVES. Copyright 1969, 1987, 1999 by Milan Kundera. English translation copyright Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1974. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For information address HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY

10022.

HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information please write: Special Markets Department, HarperCollins Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022.

All adaptations, in whatever form, are forbidden,

First Harper Perennial edition published 1999.

Designed by Nora Rosansky

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicafion Data

Kundera, Milan.

[Smesne lasky English]

Laughable Loves/Milan Kundera. p. cm.

Contents: Nobody will laugh-The golden apple of eternal desireThe hitchhiking game

SymposiumLet the old dead make room for the young deadDr. Havel after twenty years

Eduard and God.

ISBN 0-06-099703-6

1. Czech Republic-Social life and customs-Fiction. I. Title. PG5039.21.U6S58413 1999

891.8'6354-dc21 99-15600

CONTENTS

Nobody Will Laugh

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire

The Hitchhiking Game

Symposium

Let the Old Dead Make Room

for the Young Dead

Dr. Havel After Twenty Years

Eduard and God

This translation was first published in 1974, revised by the author in 1987, and in 1999 once again revised, more extensively, by Aaron Asher in collaboration with the author.

Nobody Will Laugh

"Pour me some more slivovitz," said Klara, and I wasn't against it. It was hardly unusual for us to open a bottle, and this time there was a genuine excuse for it: that day I had received a nice fee from an art history review for a long essay.

Publishing the essay hadn't been so easywhat Id written was polemical and controversial.

That's why my essay had previously been rejected by Visual Arts, where the editors were old and cautious, and had then finally been published in a less important periodical, where the editors were younger and less reflective.

The mailman brought the payment to me at the university along with another letter, an unimportant letter; in the morning in the first flush of beatitude I had hardly read it. But now, at home, when it was approaching midnight and the bottle was nearly empty, I took it off the table to amuse us.

"Esteemed comrade andif you will permit the expressionmy colleague!" I read aloud to Klara.

"Please excuse me, a man whom you have never met, for writing to you. I am turning to you with a request that you read the enclosed article. True, I do not know you, but I respect you as a man whose judgments, reflections, and conclusions astonish me by their agreement with the results of my own research; I am completely amazed by it...." There followed greater praise of my merits and then a request: Would I kindly write a review of his articlethat is, a specialist's evaluationfor Visual Arts, which had been underestimating and rejecting his article for more than six months. People had told him that my opinion would be decisive, so now I had become the writer's only hope, a single light in otherwise total darkness.

We made fun of Mr. Zaturecky, whose aristocratic name fascinated us; but it was just fun, fun that meant no harm, for the praise he had lavished on me, along with the excellent slivovitz, softened me. It softened me so much that in those unforgettable moments I loved the whole world. And because at that moment I didn't have anything to reward the world with, I rewarded Klara. At least with promises.

Klara was a twenty-year-old girl from a good family. What am I saying, from a good family? From an excellent family! Her father had been a bank manager, and around 1950, as a representative of the upper bourgeoisie, was exiled to the village of Celakovice, some distance from Prague. As a result his daughter's party record was bad, and she had to work as a seamstress in a large Prague dressmaking establishment. I was now sitting opposite this beautiful seamstress and trying to make her like me more by telling her lightheartedly about the advantages of a job I'd promised to get her through connections. I assured her that it was absurd for such a pretty girl to lose her beauty at a sewing machine, and I decided that she should become a model.

Klara didn't object, and we spent the night in happy understanding.

We pass through the present with our eyes blindfolded. We are permitted merely to sense and guess at what we are actually experiencing. Only later when the cloth is untied can we glance at the past and find out what we have experienced and what meaning it has.

That evening I thought I was drinking to my successes and didn't in the least suspect that it was the prelude to my undoing.

And because I didn't suspect anything I woke up the next day in a good mood, and while Klara was still breathing contentedly by my side, I took the article, which was attached to the letter, and skimmed through it with amused indifference.

Next page