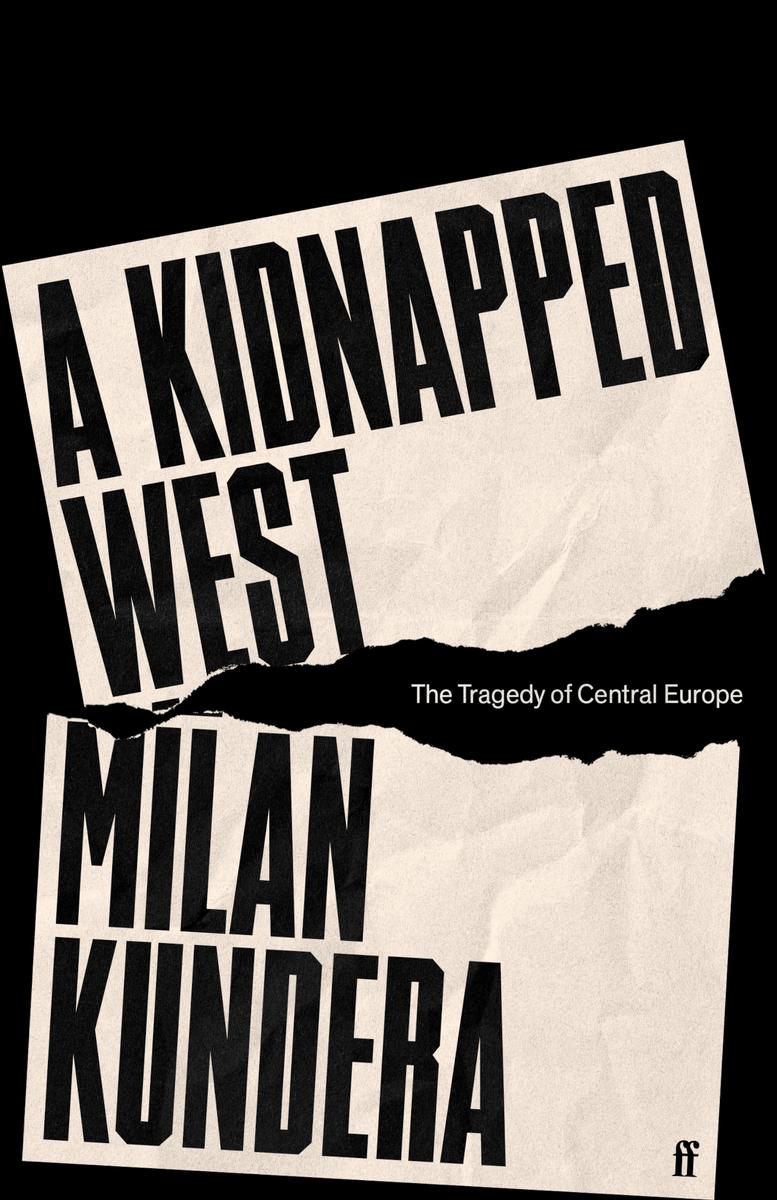

Milan Kundera - A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe

Here you can read online Milan Kundera - A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2023, publisher: Faber and Faber, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber and Faber

- Genre:

- Year:2023

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Some writers congresses are more significant, or anyhow more memorable, than the Partys. In Communist Czechoslovakia, these events were frequent and much alike. Writers conferences could also be unpredictable, and sometimes could even signal profound changes in the relations between the government and the society. Some speeches mark an era, and reading them again today has a special resonance. One such speech is Solzhenitsyns denunciation of censorship in Moscow in May 1967, which inspired Guy Barts fine song La Vrit: The poet has spoken the truth / He must be executed Less well known are the startling speeches delivered in Prague a month later at this Writers Congress, beginning with the one by Milan Kundera.

Kundera was by then a prominent writerin the theater with The Keeper of the Keys (1962); with his story collection Laughable Loves (1963, 1965); and above all with The Joke, published in 1967 (the year of that congress), a novel that both evoked an era and ended it: a book that remainsfor Czech readers but not for Czechs onlylinked to the Prague Spring of 1968. Kundera was teaching at the Prague Film School (FAMU) and had become one of the notable figures in a formidable burst of national cultural creativity. It was a time of exceptional originality and diversity: in literature (Hrabal, kvoreck, Vaculk), in theater (Havel, Topol), and especially in film (the Czech New Wave with Forman, Menzel, Nmec, Chytilov). With good reason, Kundera viewed the 1960s as a golden age of Czech culture, which was gradually shedding the ideological constraints of the government without suffering those of the marketplace. From that perspective, the Prague Spring of 1968 cannot be reduced to its political dimension and can only be understood as the culmination of a decade when the writers magazine Literrn noviny printed 250,000 copies a week and sold out on the first day; a decade in which the emancipation of the culture was speeding the dissolution of the political structure.

Assessing the danger, the ruling power sought to take back control, and the Writers Congress of June 1967 became the theater of the struggle between the writers and the regime. The premises of the conflict had been laid earlier, in the 1963 Liblice symposium on Franz Kafkaa symbolic burial of socialist realism. The work of the Prague (German-speaking) Jewish writer, starting with The Trial, reminded Czech readers, forty years later, of another kind of realism, one that was quite disturbing to the current occupant of the Prague Castlethe head of the Communist Party and of the state, Antonn Novotn.

The 1967 Writers Congress offered a number of high points: First, in his speech, the writer Pavel Kohout criticized the Soviet Blocs anti-Israel policy during the Six-Day War and then read out Solzhenitsyns famous censorship letter. This was too much for Ji Hendrych, the Party directorates watchdog for ideological orthodoxy, who abruptly left the room and, as he passed behind the rostrum where Kundera, Prochzka, and Lustig were seated, hissed a memorable Thats it, youve lost everythingabsolutely everything! The next day, Ludvk Vaculkthe author of The Axe and an editor of Literrn novinytook his turn. Seething over Hendrychs exclamation of the day before, he violated all acceptable protocol and raised point-blank the basic issue: the confiscation of power by a handful of people who want to make all the decisions. He attacked the (Partys) censorship and even the constitution. The break was complete.

Political history will, of course, preserve the explicit details of the writers conflict with the government: the temporary defeat of the writers in the summer of 1967, then their victory (also temporary) in the spring of 1968. The history of ideas will preserve, especially, Milan Kunderas opening address. Like his colleagues, he attacks state censorship, but he approaches the theme of creative freedom from another angle. Adopting a historical perspective, Kundera considers the destiny of the Czech nation, whose very existence was not a sure thing, with its elites decimated after the Battle of White Mountain (1620) and then two centuries of Germanization; he returns to the provocative question formulated in the late nineteenth century by the writer Hubert Gordon Schauer: Was it really worth investing such effort to give the Czechs back a language suited to a high culture? Would it not be wiser to blend into German culture, at the time more developed and more influential? Now, nearly a century later, Kundera rhetorically takes up Schauers question anew and offers his own answer: Such a project would only be justified by an original contribution to European culture and valuesthat is to say, the universal through the particular. The vitality of the 1960s Czech culture appears to justify that ambition, that gamble. Now that surging culture, critical to the nations very life, requires freedom to exist. The argument for cultural autonomy and freedom of thought becomes a challenge for the censoring ideologues whom Kundera calls vandals. Emancipating the culture from the grip of power clearly takes on a political dimension.

But the question Kundera raised in 1967 also carries a startlingly contemporary resonance as he anticipates its further dimension: the fate of the small nations within the vast integrationist possibilities that have opened up in the second half of the twentieth century. The process of integration risks absorbing all the small nations, whose only defense can be the vigor of their culture, the personality and the inimitable traits that are their contribution. Containing the nonviolent pressure of that integrative process within the twentieth and twenty-first centuries could turn out far more difficult than was the earlier resistance to Germanization.

Thus the discussion of the particulars of Czech cultures place continues in Kunderas reflection on the fate of the small Central European nations, and anticipates in some regard their dilemmas in a Europe that is growing ever more global. It is also the link between Kunderas speech to the 1967 Writers Congress and the essay to appear in 1983 in Le Dbat on A Kidnapped West, or The Tragedy of Central Europe.

Jacques Rupnik

The translation of The Joke was published in France (Gallimard) the day after the Soviet invasion of Prague in October 1968.

From a conversation between Milan Kundera and Antonn Liehm in Trois gnrations: entretiens sur le phnomne culturel tchcoslovaque (Three generations: conversations on the Czechoslovak cultural phenomenon). Preface by Jean-Paul Sartre (Paris: Gallimard, 1970). This conversation, which took place on the eve of the 1967 Writers Congress, may still be Milan Kunderas best intellectual self-portrait.

(1967)

My good friends,

Even though since the dawn of time no nation has lasted forever on the planet Earth, and though the very notion of nation is relatively modern, most take their own existence for grantedan obvious thing, a gift from God or from Nature, here perpetually. Their populations are able to define their culture, their political system, even their borders as their own creation, and therefore subject to debate and discussion, whereas their existence as a people they see as a given, exempt from any debate. But the troubled and disjointed history of the Czech nation, which has moved through the antechamber of death, has allowed the Czechs to avoid falling into that sort of misleading illusion; the existence of the Czech nation has never been experienced as taken for granted, obvious, and that very uncertainty is one of its major attributes.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe»

Look at similar books to A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.