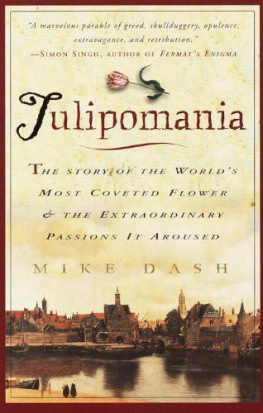

BY THE SAME AUTHOR The Limit Borderlands

For Ffion

C ONTENTS

A N OTE ON P RICES

It is impossible to make accurate comparisons between prices in the Golden Age of the Dutch Republic and those today. Figures can certainly be calculated, based on the comparative prices of gold or essential foodstuffs, but they do not take into account vital differences such as what constitutes a minimal standard of living (in many respects, people who today would be called poor live more comfortably than the richest Dutch in the seventeenth century) and certainly not what luxuries such as tulip bulbs were worth in the Golden Age.

The best comparisons probably come from looking at different salaries and earnings. The table that follows sets out some typical examples from the Dutch Republic in the first half of the seventeenth century.

The basic unit of currency in the republic was the guilder. One guilder was made up of 20 stuivers.

20 stuivers = 1 guilder

| stuiver | Cost of a tankard of beer |

| 6 stuivers | Cost of a 12-pound loaf, 1620 |

| 8 stuivers | Daily wage of an experienced Haarlem bleacher, 1601 (= about 110 guilders a year) |

| 18 stuivers | Daily wage of an Amsterdam cloth-shearer, 1633 (= about 250 guilders a year) |

| 13 guilders | Exchange price of one Dutch ton of herring, 1636 60 guilders Exchange price of 40 gallons of French brandy, 1636 |

| 250 guilders | Annual earnings of a carpenter, 1630s |

| 750 guilders | Clusiuss salary at the University of Leiden, 1592 |

| 1,500 guilders | Typical earnings of a middle-ranking merchant, 1630s |

| 1,600 guilders | Rembrandts fee for his greatest masterpiece, The Night Watch , 1642 |

| 3,000 guilders | Typical earnings of a well-off merchant, 1630s |

| 5,200 guilders | Highest reliably attested price paid for a tulip bulb, 1637 |

Sources: Deursen, Plain Lives; Hunger, Charles dEcluse; Posthumus, Inquiry; Zumthor, Daily Life in Rembrandts Holland .

They were possessed with such a Rage or,

to give it its proper Name, such an Itching for their Flowers,

as to give often three thousand Crowns for a

Tulip that pleased their Fancies;

a Disease that ruined several rich Families .

M ONSIEUR DE B LAINVILLE , T RAVELS T HROUGH H OLLAND

(L ONDON , 1743), vol. 1, p. 28

C HAPTER 1

A Mania for Tulips

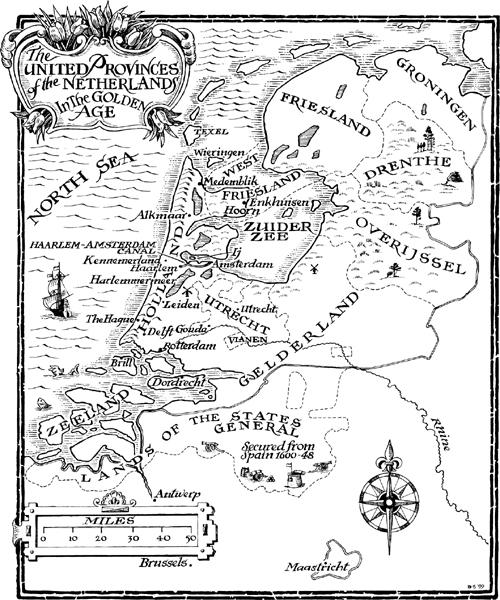

T hey came from all over Holland, dressed like crows in black from head to foot and journeying along frozen tracks rendered treacherous by the scars of a thousand hooves and narrow wheels. They had cloaked and blanketed themselves against the biting winter windthe wealthiest rattling along in unsprung carriages that jerked from rut to pothole like an untried sailor lurching through a hurricane, the rest on horseback with their heads bowed against the cold. Traveling singly or in twos and threes, they clattered through the flat and sterile landscape north of Amsterdam, riding on until they came to the little town of Alkmaar near the coast.

They were middle-aged and stoutly built: shrewd and successful men who had made their money in trade, who knew how to turn a profit and what it meant to live well. Most were clean-shaven and ruddy-faced; their clothes, though drab, were cut from the finest cloth, and the purses that they carried were snugly full of money. Passing through the gates of the town at dusk, the visitors made their way through Alkmaars cramped and narrow streets and found rooms in taverns near the busy marketplace. There they ate and drank and puffed their long clay pipes into the night, calling for great pitchers of wine and plates of roasted meats, sprawling back in their hard wooden chairs and talking shop till past midnight by the smoky, jaundice-yellow light of the peat fires in the grates.

The business of these rich Dutch merchants was not grain or spices, timber or fish. They dealt, rather, in tulip bulbsdrab and anonymous brown packages of no intrinsic worth, which resembled nothing so much as onions. Yet as unpromising as they might at first appear, flowers at this time were far more precious than the richest commodities that could be found piled up on the wharves of Amsterdam. Some tulips were so scarce and so greatly coveted that they were worth more than a hundred times their weight in gold, and successful bulb dealers could make huge profits. At this time the richest man in the whole of the United Provinces was worth 400,000 guildersa sum amassed over several generations. But some tulip traders were buying and selling single flowers for hundreds, even thousands of guilders and building paper fortunes of as much as forty or sixty thousand guilders in a matter of a year or two.

The bulb dealers had come to Alkmaar to attend an unprecedented auction. The guardians of the little orphanage in the town had come into the possession of one of the most valuable collections of tulips in the whole of the Netherlands. Caring more for the flowers value than for their beauty, they were selling off the bulbs for the benefit of some of the children in their care. So shortly after dawn broke, gray and chill, the traders began to make their way to the saleroom in the Nieuwe Schutters-Doelenthe headquarters of Alkmaars civic guard, an ornate and gabled building in the center of the town.

It was a large room, but they filled it. The bidding started briskly and soon became frantic. Single bulbs were knocked down for 200 guilders, then 400, 600, 1,000, and more. Four of the hundred or so lots were sold for in excess of 2,000 guilders apiece. And when at last the final tulip had been sold and all the money tallied, the auction proved to have raised a total of 90,000 guilders, which was, quite literally, a fortune in those days.

The date was February 5, 1637, the day flower fever reached such a pitch of frenzy in the United Provinces that once-worthless bulbs truly theatened to supplant precious metals as objects of desire. That day the tulip completed a journey that had begun hundreds of years before and thousands of miles away.

C HAPTER 2

The Valleys of Tien Shan

T he tulip is not native to the Netherlands. It is a flower of the East, a child of the unimaginable vastness of central Asia. So far as anyone can tell, it did not reach the United Provinces until 1570, and by then it had already been journeying for many hundreds of years from its original homeland in the mountain ranges that run north of the Himalayas along the fortieth parallel.

Taxonomists believe that the first tulips sprang from the scrubby slopes of the Pamirs and flourished among the foothills and valleys of the Tien Shan Mountains, where China and Tibet meet Russia and Afghanistan in one of the least hospitable environments on earth. They were relatively sober and compact things, with narrower petals and much less flamboyant variegation than Dutch tulips. The flowers of the Tien Shan were much shorter than modern tulips, carrying their petals usually a scant few inches from the ground. But they were hardy and well adapted to survive the harsh winters and parched summers of central Asia.