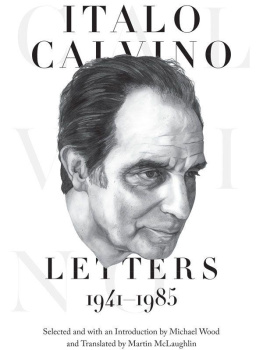

ITALO CALVINO

LETTERS, 19411985

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press

Notes from Lettere 19411985 , edited by Luca Baranelli 2000 Arnoldo Mondadori Editore

S.p.A., Milano. All rights reserved

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration: Italo Calvino , 2012, by Michael Molloy. Illustration based on photograph

Italo Calvino , by Jerry Bauer.

All Rights Reserved

Second printing and first paperback printing, 2014

Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-16243-0

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows

Calvino, Italo.

[Correspondence. Selections]

Italo Calvino : letters, 19411985 / selected and with an introduction by Michael Wood ; translated by Martin McLaughlin.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13945-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Calvino, ItaloCorrespondence. 2. Authors, Italian20th centuryCorrespondence. I. Wood, Michael, 1936editor. II. McLaughlin, M. L. (Martin L.), translator. III. Title.

PQ4809.A45Z48 2013

856.914dc23

2012038719

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Translation is supported by a bequest from Charles Lacy Lockert (18881974)

This book has been composed in MVB Verdigris Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

, by Michael Wood |

, by Martin McLaughlin |

Introduction

MICHAEL WOOD

ITALO CALVINO WAS DISCREET ABOUT HIS LIFE AND THE LIVES of others, and skeptical about the uses of biography. He understood that much of the world we inhabit is made up of signs, and that signs may speak more eloquently than facts. Was he born in San Remo, in Liguria? No, he was born in Santiago de las Vegas, in Cuba, but since an exotic birth-place on its own is not informative of anything, he allowed the phrase born in San Remo to appear repeatedly in biographical notes about him. Unlike the truth, he suggested, this falsehood said something about who he was as a writer, about his creative world (letter of November 21, 1967), the landscape and environment that shaped his life (April 5, 1967).

This is to say that the best biography may be a considered fiction, and Calvino was also inclined to think that a writers work is all the biography anyone really requires. In his letters he returns again and again to the need for attention to the actual literary object rather than the imagined author. For the critic, the author does not exist, only a certain number of writings exist (November 24, 1967). A text must be something that can be read and evaluated without reference to the existence or otherwise of a person whose name and surname appear on the cover (July 9, 1971). The public figure of the writer, the writer-character, the personality-cult of the author, are all becoming for me more and more intolerable in others, and consequently in myself (September 16, 1968).

Such assertions begin to conjure up what came to be known as the death of the author, although still only as a prospect or a principle, and in a lecture called Cybernetics and Ghosts, Calvino explored the

This last sentence makes clear that Calvino is talking about a finished work and its life in the world, and not about some sort of unattainable impersonality: self and society may have become ghosts, but they are essential. The death of the grandee author in no way implies the disappearance of the writing person, and any appearance of contradiction vanishes as soon as we understand that for Calvino and many others, writing is life. We are people, there is no doubt, who exist solely insofar as we write, otherwise we dont exist at all (August 24, 1959). The death of the author may indeed be the liberation of the writer, and for Calvino there is also an ethical element in this disposition. Books, he says, in the end represent the best of our conscience (July 22, 1958). They are not always what we wish they were, but they show us what we ourselves could be. Books are unavoidably personal for Calvino, but not confessional, and not only personal.

But then what are we to make of the letters of such a writer, and what are we doing reading them? In part we are, Im afraid, ignoring his warnings and careful distinctions; peeping into his privacy. These letters were not written for us or to us. We see that young man, as Calvino later calls his earlier self (May 26, 1977), in all his unruly literary excitement, his half-hearted agricultural studies, his worries about conscription, followed by his departure to join the partisans. He returns from the war a declared Communist but still a diverse and witty stylist. The letters reflect his encounters with the writers Elio Vittorini and Cesare Pavese, both of whom meant a great deal to him, and record many of his exchanges of thoughts with friends and critics. He travels to Russia and America, reporting in detail on his impressions; resigns from the Communist Party; continues to work at the Turin publishing house Einaudi. He marries the Argentinian Esther Singer and they have a daughter, Giovanna, who appears in the letters as happy, alert, and admirably resistant to education (she speaks three languages and has no wish to learn to read or write [March 1, 1972]). Calvino moves to Paris; then Rome, a place that young man once swore he would never set foot in. There are kindly letters to scholars and school-children, quarrelsome exchanges with figures like Pier Paolo Pasolini and Claudio Magris. Calvino discovers the Sicilian writer Leonardo Sciascia, makes clear his admiration for Carlo Emilio Gadda, thinks about film with Michelangelo Antonioni, and collaborates on opera with Berio.

There are dramatic moments, albeit quietly evoked. He dates a letter to his friend Eugenio Scalfari the first night of the curfew imposed by the Germans (September 1213, 1943); sends a message on a notepad to his parents from a partisan hiding place; in another letter mentions his parents being taken hostage and then released (my father was on the point of being shot before my mothers eyes) (July 6, 1945). Calvino is constantly exercised by Italian politics. We have his letter of resignation from the Italian Communist Party (August 1, 1957). He witnesses the events of May 1968 in Paris. He thinks about Brazilian prisons, Palestinian poets, the war in Vietnam. In Cuba he meets Che Guevara.

And again and again, we encounter Calvino the voracious reader: as a young man catching up with Ibsen and Rilke and what seems to be the whole of western literature, paying attention to contemporary Italian writers of all stripes; as a prolific reviewer reading books to review immediately, as he says (January 16, 1950); as a man who spent most of his adult life working as an editor in a publishing house. A collection of his letters in Italian is called I libri degli altri ( Other Peoples Books ), a phrase itself taken from a casual, generous remark of Calvinos: I have spent more time with other peoples books than with my own. He added, I do not regret it. a period of depression and writers block which has gone on for some time now and maybe wont ever unblock (January 11, 1976), or tells a correspondent that he has only progressed towards rarefaction and silence. In recent years, he says wryly, I was very satisfied playing the dead man for a bit: how clever I am at not publishing! Whereas now I am starting again to realize that the one thing I would like is to write but I have managed to lose all love for images of contemporary life (May 6, 1972). He regains this love, but the loss was real while it lasted. All the late work, beautifully written as it is, shows a greater and greater attention to what cannot be said.

Next page