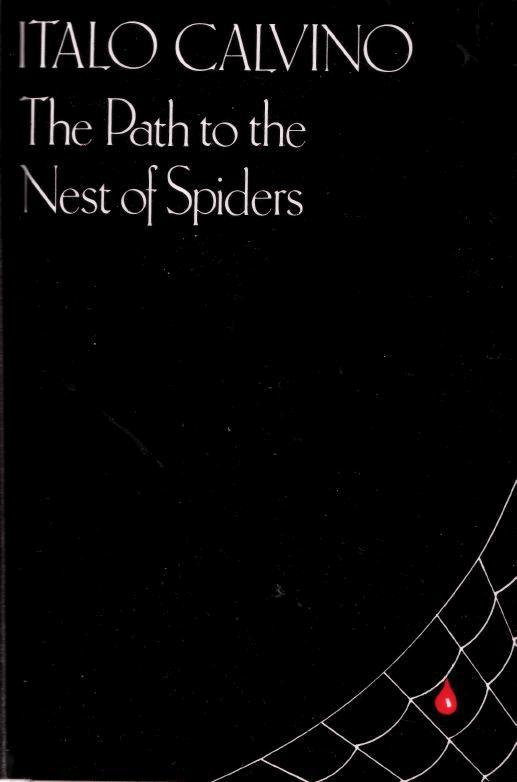

ITALO CALVINO

The Path to the Nest of Spiders

Translated from the Italian hy Archibald Colquhoun

With a preface hy the author translated hy William Weaver

Copyright 1947

Preface translation copyright 1976

ISBN 0-912946-31-8

This was my first novel; I can almost say it was my first piece of writing, apart from a few stories. What impression does it make on me now, when I pick it up again? I read it not so much as something of mine but rather as a book born anonymously from the general atmosphere of a period, from a moral tension, a literary taste in which our generation recognized itself, at the end of World War II.

Italy's literary explosion in those years was less an artistic event than a physiological, existential, collective event. We had experienced the war, and we younger peoplewho had been barely old enough to join the partisansdid not feel crushed, defeated, "beat." On the contrary, we were victors, driven by the propulsive charge of the just-ended battle, the exclusive possessors of its heritage. Ours was not easy optimism, however, or gratuitous euphoria. Quite the opposite. What we felt we possessed was a sense of life as something that can begin again from scratch, a general concern with problems, even a capacity within us to survive torment and abandonment; but we added also an accent of bold gaiety. Many things grew out of that atmosphere, including the attitude of my first stories and my first novel.

This is what especially touches us today; the anonymous voice of that time, stronger than our still-uncertain individual inflections. Having emerged from an experience, a war and a civil war that had spared no one, made communication between the writer and his audience immediate. We were face to face, equals, filled with stories to tell; each had his own; each had lived an irregular, dramatic, adventurous life; we snatched the words from each other's

mouths. With our renewed freedom of speech, all at first felt a rage to narrate: in the trains that were beginning to run again, crammed with people and sacks of flour and drums of olive oil, every passenger told his vicissitudes to strangers, and so did every customer at the tables of the cheap restaurants, every woman waiting in line outside a shop. The grayness of daily life seemed to belong to other periods; we moved in a varicolored universe of stories.

So anyone who started writing then found himself handling the same material as the nameless oral narrator. The stories we had personally enacted or had witnessed mingled with those we had already heard as tales, with a voice, an accent, a mimed expression. During the partisan war, stories just experienced were transformed and transfigured into tales told around the fire at night; they had already gained a style, a language, a sense of bravado, a search for anguished or grim effects. Some of my stories, some pages of this novel originated in that new-born oral tradition, in those events, in that language.

But... but the secret of how one wrote then did not lie only in this elementary universality of content; that was not its mainspring (perhaps having begun this preface by recalling a collective mood has made me forget I am speaking of a book, something written down, lines of words on the white page). On the contrary, it had never been so clear that the stories were raw material : the explosive charge of freedom that animated the young writer was not so much his wish to document or to inform as it was his desire to express. Express what? Ourselves, the harsh flavor of life we had just learned, so many things we thought we knew or were, and perhaps really knew and were at that moment. Characters, landscapes, shooting, political slogans, jargon, curses, lyric flights, weapons, and love-making were

only colors on the palette, notes of the scale; we knew all too well that what counted was the music and not the libretto. Though we were supposed to be concerned with content, there were never more dogged formalists than we; and never were lyric poets as effusive as those objective reporters we were supposed to be.

For us who began there, "neorealism" was this; and of its virtues and defects this book is a representative catalogue, born as it was from that green desire to make literature, a desire characteristic of the "school." Some people today recall "neorealism" chiefly as a contamination or constraint suffered by literature for extraliterary reasons, but this view shifts the terms of the question. Actually the extraliterary elements stood there so massive and so indisputable that they seemed a fact of nature; to us the whole problem was one of poetics; how to transform into a literary work that world which for us was the world.

"Neorealism" was not a school. (We must try to state things precisely.) It was a collection of voices, largely marginal, a multiple discovery of the various Italys, even or particularlythe Italys previously unknown to literature. Without the variety of Italys unknown (or presumedly unknown) to one another, without the variety of dialects and jargon that could be kneaded and molded into the literary language, there would have been no "neorealism." But it was not provincial, in the sense of the regional verismo of the nineteenth century. Local characterization was intended to give the flavor of truth to a depiction in which the whole wide world was to be recognized: like the rural America of those 1930s writers whose direct or indirect disciples so many critics accused us of being. Therefore language, style, pace had so much im

portance for us, for this realism of ours which was to be as distant as possible from naturalism. We had drawn a line for ourselves, or rather a triangleVerga, Vittorini, Pavese from which to set out, each on the bases of his own local vocabulary and his own landscape. (I continue speaking in the plural, as if I were referring to an organized, conscious movement, now when I am explaining it was just the opposite. How easy it is, when you talk of literature, even in the midst of the most serious, factual discussion, to shift unaware to inventing stories.... For this reason discussions of literature irritate me more and more the talk of others and my own as well.)

My landscape was something jealously mine (and this is where I could begin my preface: reducing to the minimum the "autobiography of a literary generation" lead, starting at once to speak of what concerns me directly, perhaps I can avoid being generic, approximate....), a landscape that no one had ever really put on paper. (Except for the poet Montalethough he was from the other Ligur-ian RivieraMontale, who I thought could be read as memory of our common landscape, in both his images and his vocabulary.) I came from the Riviera di Ponente; from the landscape of my city, San Remo, I polemically erased all the tourist shorethe sea front with its palm trees, casino, hotels, villasas if I were ashamed of it. I began from the narrow alleys of the Old City, I climbed up the stream beds, I shunned the geometrical fields of carnations, I preferred the terraces of vineyards and olive groves with crumbling old dry walls, I ventured along the mule-tracks over the sedge-covered hills, up to where the woods begin, pines first, then chestnuts, and so I had gone from the seaalways visible from above, a stripe between two

green flanksto the tortuous valleys of the Ligurian Pre-Alps.

I had a landscape. But if I was to depict it, it had to become secondary to something else: to people, to stories. The Resistance represented the fusion of landscape with people. The novel I would never have been able to write otherwise is here. The daily scene of my whole life had become entirely extraordinary and adventurous: a single story unwound from the dark arches of the Old City up to the woods. It was the pursuit and the concealment of armed men. I succeeded in depicting even the villas, now that I had seen them requisitioned and transformed into guardhouses and prisons; even the fields of carnations, since they had become a no man's land, dangerous to cross, evoking a rattle of automatic fire in the air. It was from this possibility of setting human stories in landscapes that "neorealism"...

Next page